Enough already: voters hit with ads, calls

RICHMOND, Va. People who live in battleground states tend to have a number and a coping strategy.

Virginian Catherine Caughey's number is four: Her family recently got four political phone calls in the space of five minutes.

Ohioan Charles Montague's coping mechanism is his TV remote. He pushes the mute button whenever a campaign ad comes on.

All the attention that the presidential campaigns are funneling into a small number of hard-fought states comes at a personal price for many voters.

The phone rings during a favorite TV show. Traffic snarls when a candidate comes to town. A campaign volunteer turns up on the doorstep during dinner. Bills get buried in a stack of campaign fliers. TV ads spew out mostly negative vibes.

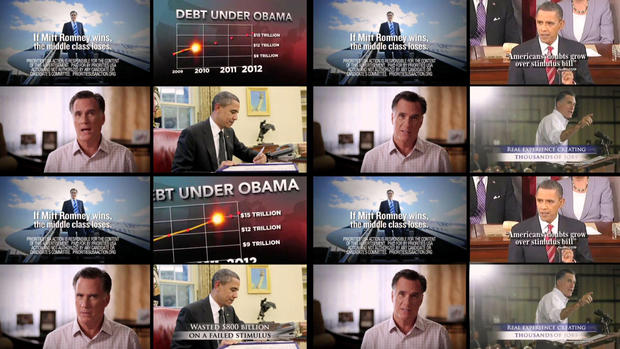

- New Romney ad forecasts costs of "four more years"

- Pro-Obama group revisiting Romney's Bain record

- Full coverage: Campaign 2012

The effects are cumulative.

"It's just too much," says Carmen Medina, of Chester, Va.

"It's becoming a little too overwhelming."

Medina, it should be noted, is an enthusiastic supporter of Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney. She squealed with joy outside the United Latino Market in Richmond when she learned that Romney had just appeared at a rally across the street.

But she's starting to block phone numbers to Make. The. Calls. Stop.

Even Ann Romney, the candidate's wife, has had enough. "I don't want to get myself upset so I am not watching television for the moment," she told the women on ABC's "The View" on Thursday.

"Trust me, the audience members that are in swing states are sick of them," she said of political ads.

Ditto the president.

"If you're sick of hearing me approve this message, believe me, so am I," Barack Obama said during the Democratic National Convention.

The parties speak with pride of their massive ground operations - the door knockers, the phone banks, the campaign signs and more.

They trumpet the higher level of activity this year than in 2008.

With the campaign now focused on just nine states - Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Virginia and Wisconsin - the parties are able to target their resources narrowly.

Republicans say they've made three times more phone calls and 23 times more door knocks in Ohio than they had by this time in 2008, for example, and nearly six times more phones calls and 11 times more door knocks in Virginia. Democrats don't give out that level of detail, but describe ambitious outreach activities from their 60-plus field offices in Virginia and 125 in Ohio.

The campaigns and independent groups supporting them are expected to pour about $1.1 billion into TV ads this year, the vast majority of it in the most competitive states.

But does all of this activity reach a point of diminishing returns? Is there a risk of overkill?

Not to David Betras, chairman of the Democratic Party in Ohio's Mahoning County. He considers himself a field general in the battle

to re-elect Obama, and enthusiastically details the party's efforts on his turf.

"Is there a saturation point? I haven't heard that," he says.

"I think just the opposite. I think people, at least in my neck of the woods, are kind of excited that they're playing such an important role."

But he does say, "Some people you call and of course they're burned out with it, and you thank them very much and you move on."

Clearly, more exposure doesn't always translate into more support.

"The more I see Romney, the less I like," says Kay Martin, who lives in the Denver suburb of Arvada.

And if not generating a backlash, some of that political activity is surely just wasted energy.

Gwynnen Chervenic, in Alexandria, has taught her kids to yell "lies" any time a political ad comes on.

"I'm trying to make sure they develop a healthy skepticism about the election PR process," she explains. "Makes me laugh every time and should help ease the pain until Election Day."

A Fairfax County woman who's a strong Romney supporter emails: "I don't mind telling the Romney campaign or the RNC (Republican National Committee) that I am voting for Romney, but why do I have to tell them that MULTIPLE times?"

She's ready to start giving out a phony phone number. But she doesn't want to be identified by name - because her husband's working for the Romney campaign. And, yes, she even went with him recently to knock on doors.

"But I was so uncomfortable knocking on people's doors in the evening because I felt like I was doing the very thing that bothers me," she admits.

Political psychologist Stanley Renshon, a professor at City University of New York, said most Americans don't spend a lot of time thinking about politics, and don't particularly like being the focus of too much political attention.

But the campaigns just won't - or can't - stop reaching out.

"They can't not try to win your vote, even at the risk of alienating your vote," says Renshon. "You don't want to regret not doing everything you can do."

John Geer, a political science professor at Vanderbilt University, says it's the political equivalent of an arms race, and neither side dares stop the carpet bombing.

"We don't know exactly where saturation occurs, but I think we're way past that," he says.

For those from less competitive states, the number and tone of ads can be jarring.

"I think people are just upset about the lies," says Pamela Ash, a 66-year-old Obama volunteer from Arizona who's been visiting her brother in Ohio to help the campaign. "Enough already. I just can't stand it."

Even the people making the calls understand the annoyance.

Maria Buzzi estimates that 10 percent to 15 percent of the calls she makes during her volunteer shift at Romney's Stow, Ohio, offices end with frustrations.

"I've been called a G-D, F-ing B," the 67-year-old retired nurse and grandmother said. "I'm a sensitive person and they are just vicious. It hurts my feelings and I take it personally. But I really want to help Mitt Romney."

After those tough calls, she hangs up and takes a moment to compose herself. Then she picks up the phone and dials another voter.

Maybe one of her calls will end up in tiny Payson, Utah, about as far from the political front as you can get this year.

That's where Katie Peterson lives. She moved there from Ohio four years ago.

Says Peterson: "Somehow all those people making the phone calls think I still live there and that they need to call all the time."