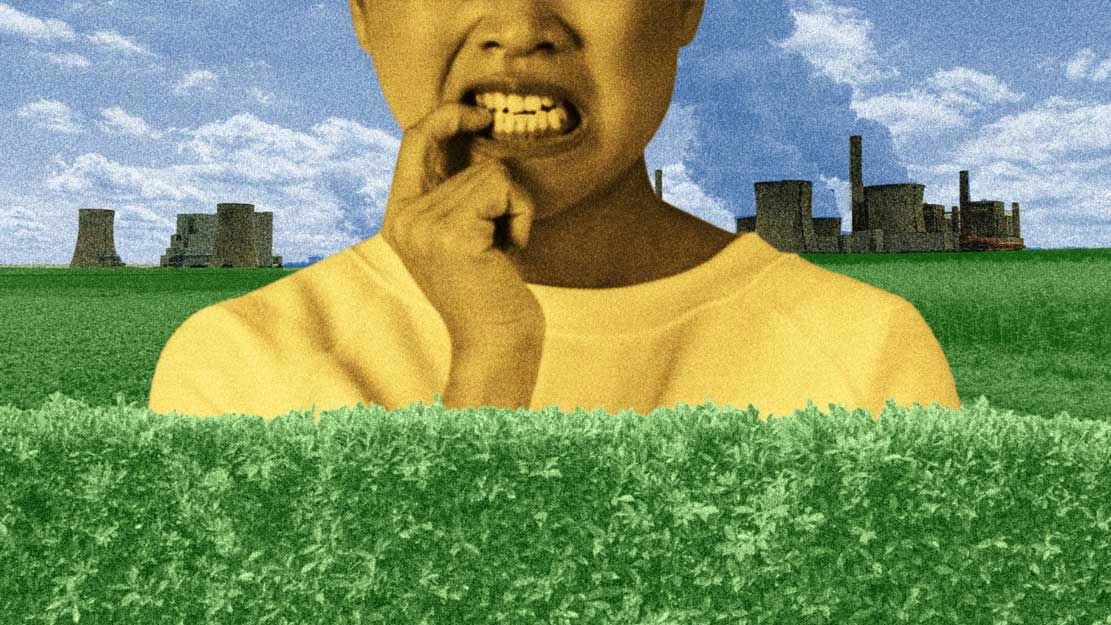

Emissions rise despite support for more renewable energy

Support for clean energy in the U.S. has risen to record highs in recent surveys, but adoption of those clean energy sources is lagging far behind.

While a record number of coal-fired power plants were retired last year, their energy production was mostly replaced by natural gas instead of renewable energy like wind or solar, according to a report by independent research provider Rhodium Group. The report estimates that in 2018 the U.S. posted the largest increase in heat-trapping carbon dioxide emissions since 2010, up 3.4 percent.

Before 2018, the U.S. had three straight years of emissions declines despite economic growth. But last year the economy grew faster, illustrating the difficulty of kicking our addiction to fossil fuels when our economic engine revs up. Rhodium Group explains, "Some of this was due to unusually cold weather at the start of the year. But it also highlights the limited progress made in developing decarbonization strategies."

Many Americans support making that transition. A March 2018 study, "Politics and Global Warming," by researchers at Yale and George Mason Universities, finds majority support across party lines for developing cleaner energy.

In that survey, 87 percent of registered voters (94 percent of Democrats and 79 percent of Republicans) favor funding more research into renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power.

These views are echoed in a recent Pew Research Center study which found "large majorities of Americans favor expanding at least two types of renewable sources to provide energy: solar panel (89%) and wind turbine (85%) facilities."

At a time when political polarization divides Americans on so many issues, these points of agreement may seem surprising. But agreement is not enough. For an energy transition to happen, policy and incentives are needed.

"For people, corporations, and governments to take action they're going to have to have incentives," William Nordhaus, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on putting a price on carbon, wrote in a recent Yale Alumni Magazine article.

Incentives require specific government policy action. We can find clues to why this is tough to come by deeper in the Pew study. While Democrats are generally supportive of policies to combat climate change, most Republicans are skeptical. Nearly three-quarters of Republicans or Republican-leaning voters say these policies either make no difference or do more harm than good, and 57 percent think such policies harm the economy.

But there are signs of growing support for market-driven solutions among younger conservatives. According to the Pew study, "Republican Millennials are less inclined than their elders in the GOP to support increased use of fossil fuel energy sources through such methods as offshore drilling, hydraulic fracturing and coal mining. For example, 75% of Republicans in the Baby Boomer and older generations support the increased use of offshore drilling, compared with 44% of Millennial Republicans."

Former Congressman Ryan Costello (R-Pennsylvania) just left the U.S. House of Representatives and is now the new managing director of Americans for Carbon Dividends, an advocacy affiliate of the Climate Leadership Council. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed this week he laid out the case for a Republican plan to tackle climate change, citing, in part, the need to keep younger Republicans on board.

In his new work, Costello is aiming to advance a plan by former GOP Secretaries of State James Baker and George Shultz, fine-tuning the details of a bill which would put a fee on carbon dioxide emissions and return the proceeds to individuals and families on a quarterly basis.

The plan claims, "Over two-thirds of American households would be financial winners under a carbon dividends program, including the most vulnerable." The aim is to increase the cost and disincentivize use of products that generate carbon pollution, encouraging industries and consumers to opt for greener alternatives instead.

Even though the group says its carbon fee plan would return money to Americans' pockets, it may still be seen as a tax. In reply, Costello says, "I learned in Congress that no major policy solution comes without simplified rebuttals, which often aren't accurate. If families are receiving a check every three months and carbon emitters are transitioning to the cleaner energy, everyone comes out ahead."

Ed Maibach is a professor at George Mason University's Center for Climate Change Communication and co-author of the "Politics and Global Warming" study. Commenting in general on policy, not specifically on the Climate Leadership Council plan, he says his public opinion research "finds strong support for a range of climate solutions policies, even when we mention the costs explicitly. Sometimes, policy support actually increases when we mention the estimated cost per household, for example, about 50 cents per day, probably because the projected costs strike people as a good deal."

Besides work on the bill, Costello plans to spend his time on education, advocacy and building grassroots coalitions that "allow people to kick the tires" on climate policy.

He recognizes he has an uphill battle selling this to Congress. But he says, "You can't solve big challenges without ambitious solutions. That's what this seeks to do."