Emerging GOP line: Obama has made America a follower

President Obama's handling of the Libya crisis is prompting Republican criticism that he is turning America from the world's leader into a mere follower - a country all too ready and willing to take orders from even the French.

"When we have [French] President [Nicolas] Sarkozy dictating the pace and terms and conditions for security initiatives in the world, we know that we've entered a new era in terms of America's place and leadership and vision for security around the world, and that concerns me greatly," former Minnesota governor Tim Pawlenty, who just announced a presidential exploratory committee, said Monday.

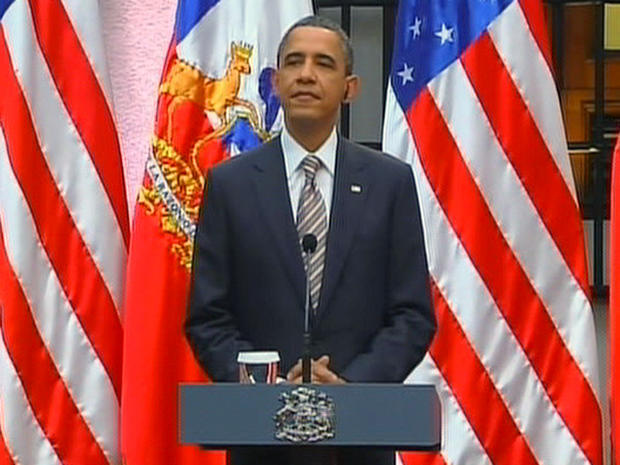

Speaking from Chile Monday afternoon, Mr. Obama again stressed that America is working "with our international partners" on the offensive against Libyan leader Muammar Qaddafi, stating the action has been solely "in support of an international mandate from the Security Council." Longtime Republican strategist Ed Rollins says that sort of rhetoric presents an opportunity to critics like Pawlenty, who can point to it as evidence that Mr. Obama doesn't see America as the preeminent nation in the world.

"To a Republican audience, it's what they want to believe," said Rollins. "They want to believe the president is weak and hasn't been decisive."

That perception may have been reinforced over the weekend with a spate of stories like this one in the New York Times, which suggested that a trio of women - Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Senior National Security Council aide Samantha Power and ambassador to the United Nations Susan Rice - pushed Mr. Obama to take a harder line with Libya.

The White House tried Monday to rebut that narrative, with a senior administration official maintaining that Mr. Obama has led the debate and telling Politico that Clinton and Power weren't present in the meeting where he made his decision. It has good reason to push back: No president wants to be seen, particularly in an era of lingering sexism and anti-French sentiment, as being told what to do by a coalition of women and a country populated by what some conservative commentators are prone to call "cheese eating surrender monkeys."

Mr. Obama has cast the Libya offensive as an international effort in part to keep it from further ginning up anti-American sentiment in a region where American military intervention has already generated significant anger. In the run-up to the attacks, he repeatedly stressed the Arab league's call for a no-fly zone as well as the consensus represented by the Security Council vote to take action if Qaddafi did not change his ways. Following the anti-Bush doctrine rhetoric from his campaign, he cast the Libya effort as reflecting the world acting together to stop a humanitarian crisis - not the latest example of America getting involved in a part of the world where it does not belong.

That's part of the reason that it French airplanes conducted the initial flights into Libya. The subsequent attacks have come largely in the form of American missiles, but the French flights helped push the argument that America is merely a participant in what, this time around, really is a coalition of the willing.

Fitting with this line of reasoning, the White House said Monday that it will hand responsibility for coordinating the offensive over to coalition partners within days. Mr. Obama, meanwhile, argued that his course of action has allowed the United States to keep from having to shoulder the burden of the military intervention alone.

"Our military's already very stretched and carries large burdens all around the world," he said. "And whenever possible, for us to get international cooperation, not just in terms of word but also in terms of planes and resources and pilots, that's something that we should actively seek and embrace because it relieves the burden on our military and it relieves the burden on U.S. taxpayers to fulfill what is an international mission and not simply a U.S. mission."

Yet according to Rollins, Mr. Obama's handling of the situation - which has included continuing a trip to Latin America despite the crisis, and authorizing military action from foreign soil - has fueled perceptions that he "doesn't look like he's in charge, or wants to be in charge." His decision to cast America's actions as part of a larger effort, pragmatic though it may be, has provided fodder for potential general election opponents like Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich, who have shown themselves eager to cast Mr. Obama as a leader who sees America as less than exceptional.

Romney pointedly titled his most recent book "No Apology: The Case For American Greatness," arguing inside that Mr. Obama has been overly apologetic about America's role in the world and has presided over a "misguided and bankrupt" shift away from American exceptionalism. Gingrich, meanwhile, said last August that "to deny American exceptionalism is in essence to deny the heart and soul of this nation."

Ultimately, the political impact of the president's handling of the Libya crisis won't become clear until the situation plays out, and it will depend in large part on whether Qaddafi is able to hang onto power. But for his critics, Mr. Obama's posture that America is an equal in the fight -- not a leader -- is further evidence that the country needs someone new in charge come 2012.