Elizabeth Warren reignites feud with Joe Biden over personal bankruptcy policy

Elizabeth Warren reignited a dormant feud she's had with Joe Biden for two decades over how the country should handle personal bankruptcies.

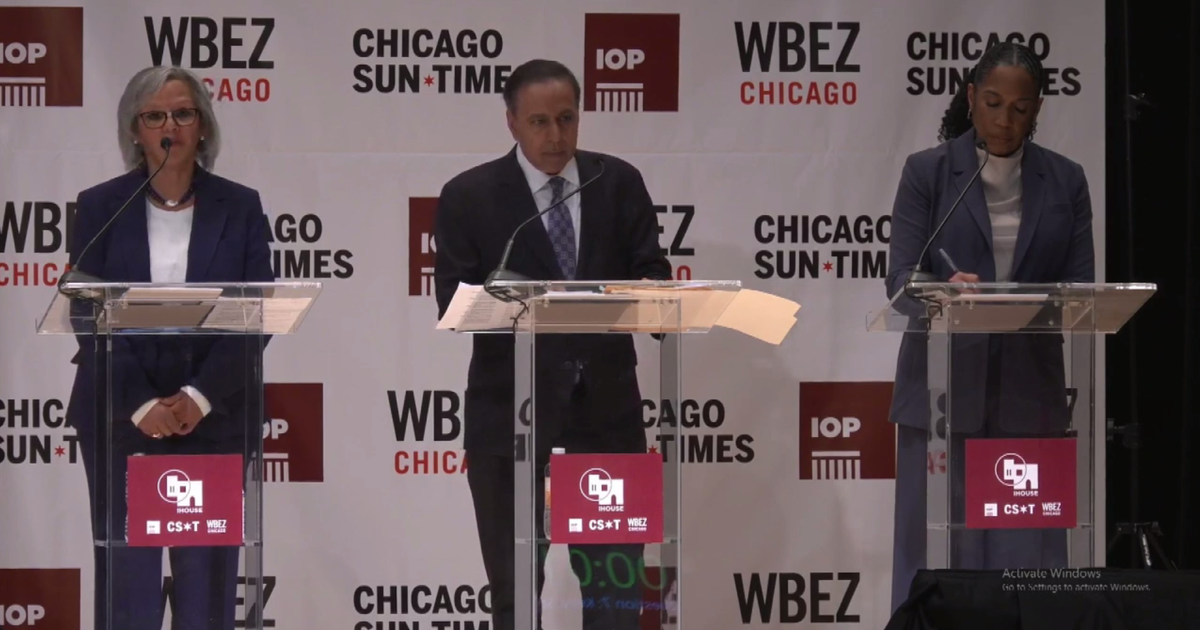

In 2005, Warren, then a professor at Harvard, faced off with Biden in a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing over the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act (BAPCPA), a bill meant to bring down the number of personal bankruptcies filed in the U.S. Biden had long championed the Republican-backed bill's provisions, and Warren had fought against them. With Democrats, including Hillary Clinton, eventually voting in favor of the bill, Warren lost her most public political battle up to that point in her career.

Bankruptcy isn't as central to Biden's identity as it is to Warren, and while Senator Bernie Sanders has also attacked Biden for his role in the 2005 vote, Biden himself rarely talks about bankruptcy policy on the trail.

In a 12-page plan posted to Medium, Warren outlined how she'd undo the "harmful provisions" in BAPCPA and proposes several other changes to the country's bankruptcy law.

"By making it harder for people to discharge their debts and keep current on their house payments, the 2005 bill made the 2008 financial crisis significantly worse," she argued.

In her view, the law governing personal personal bankruptcy adds too much red tape for families declaring bankruptcy and limiting the incomes of those who can file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy. Warren's version of bankruptcy would free individuals from all their debt after they have forfeited all their liquid assets. She calls for a merger of Chapter 7 and 13 bankruptcies, that would create a "menu of options" protecting Americans from having to file for Chapter 13 bankruptcy, which demands individuals continue to pay their debts over time. She would also allow student loans to be discharged in bankruptcy. Under current law, those who declare bankruptcy are not released from paying back their student loans.

Warren's plan also includes a suite of bankruptcy protections and pro-borrower policies, including allowing people to modify their mortgagees in bankruptcy. But she also takes aim at ways in which bankruptcy can disproportionately help the rich, closing the "Millionaire's Loophole" that allows an individual to shield money in a trust from creditors' claims.

Bankruptcy was at the heart of Warren's academic career. "I spent most of my career studying one simple question: why do American families go broke?" she wrote.

In her Medium post, Warren said she entered politics — with her work on a commission reviewing bankruptcy laws in the 1990s — only because of "the stories I had come across in our research."

Her bankruptcy work was largely empirical, but also weathered some criticism. As The Washington Post reported earlier this year, another scholar complained to the National Science Foundation (NSF) that her 1989 book included "repeated instances of scientific misconduct." The NSF's watchdog investigated the case and concluded that the allegations "were not misconduct under our regulation," finding that the disputes between the scholar and Warren and her co-author were the result of misunderstandings and "extreme differences" of opinion "regarding the interpretation of data."

In another instance, a report Warren co-authored in 2005 (and updated in 2009) while she was a Harvard professor stated that "using a conservative definition, 62.1% of all bankruptcies in 2007 were medical." Politifact noted that critics said the report relied too heavily on personal interviews and their own claims that medical bills had pushed them into bankruptcy. It pointed to an analysis by David Dranove and Michael Millenson at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern that assessed that a causal link to medical problems was evident in just 17% of personal bankruptcies.

Warren's plan is based on the idea, shared in her research, that bankruptcies are often the result of bad luck and shouldn't be overly punitive. Like many of the progressive candidate's plans, this one included a section on racial and gender disparities in the bankruptcy system. "Bankruptcy doesn't affect all people equally. It mirrors the systemic inequalities in our economy," she wrote.

This is an argument she's been making, and an area where she's been attacking Biden since before the Senate Judiciary Committee hearing where they battled in 2005.

"Senators like Joe Biden should not be allowed to sell out women in the morning and be heralded as their friend in the evening," she wrote in her book released the year before their fight.