Elizabeth Warren bets big on policy to break through crowded Democratic field

Among the collection of T-shirts sold on Elizabeth Warren's campaign website, there is one that encapsulates her approach to the campaign so far: "Warren has a plan for that."

It's undoubtedly true that Warren, among the nearly two-dozen Democrats running for president in 2020, has the most detailed policy platform. She wants to break up big tech and protect public lands. She wants to abolish the Electoral College and implement a new "ultra-millionaires tax." She wants to relieve student debt, decrease mortality rates during child birth among black women, and break up the big technology companies.

Warren has taken a clear stand on just about every major political issue facing the country, and even some more esoteric ones, while many of her opponents eschew policy minutiae. She has a vision. She has an agenda.

And despite being the first major candidate to enter the race last December, she's lagging in the polls.

In 2016, Warren's progressive bonafides had liberals begging her to challenge Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination. The activist group MoveOn planned to spend $1 million on a "Draft Warren" effort. But Warren ultimately demurred, giving Sen. Bernie Sanders a clear path to challenge Clinton from the left.

This year, Warren is trailing in the money race. In the first quarter of 2019, she raised $6 million in donations — although she did have $12 million left in her account from her 2018 Senate race. Sanders, meanwhile, pulled in $18 million. California Sen. Kamala Harris raised $12 million, and former Rep. Beto O'Rourke brought in a $9 million haul. In his first day as a declared candidate last week, former Vice President Joe Biden raised $6.3 million, which is more than Warren had brought in after months on the trail.

Even Pete Buttigieg, the small-town mayor and subject of several glowing profiles, raised $7 million in the first quarter.

Depending on who you ask, there's no shortage of reasons why Warren might be struggling at this early stage of the campaign. Her first finance director departed early, disagreeing with Warren's resolution not to spend time holding large fundraisers. She has a polarizing reputation, in part due to questions surrounding her claimed Native American heritage. In her solidly Democratic home state of Massachusetts, she received fewer votes in the 2018 election than Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican who was also up for re-election.

The Iowa caucus is nine months away, the first Democratic debate is at the end of June, and the race is just beginning to take shape.

"Warren has a plan for that." But are her plans enough to propel her to the front of the pack?

Running to the left, struggling in the middle

Warren has been squarely in the middle in most polls, although a few recent ones have shown her on the rise. According to FiveThirtyEight, Warren is averaging at fifth place in the polls, with numbers in the high single digits. A CNN poll published Tuesday, however, did find Warren in third place with 8 percent support, and a Quinnipiac poll showed Warren in second place with 12 percent support.

Although Biden leads in these two polls by 25 percentage points, Warren's camp hopes this mild surge in support means her policy-first campaign is finally gaining traction with voters.

"Elizabeth's ideas are all about one central goal: to make government, our economy, and our democracy work for everyone, not just the wealthy and well-connected," John Donenberg, the policy director for the Warren campaign, told CBS News. "Every proposal tackles this same issue within its relevant context."

Donenberg leads a small team, with most members having worked with Warren in the Senate. The campaign's policy proposals stem from Warren's work in the Senate and "decades of Elizabeth's research and advocacy."

Donenberg said Warren often consults experts when developing her plans. She spoke with affordable housing groups like the National Low Income Housing Coalition and leaders like Darrick Hamilton and Mehrsa Baradaran when developing her proposal to address the legacy of redlining and decrease the racial wealth gap.

Warren's campaign says her political views are shaped by her personal experience, and "having a plan" has been part of her presidential campaign since the beginning. She often discusses how her father lost his job and eventually wound up as a janitor. Her two parents, both earning minimum wage, were able to support Warren. But she says minimum wage alone is no longer enough to raise a family, so we must tax the wealthy to pay for universal childcare.

"She's lived opportunity and wants that for every kid in America," Donenberg said. "Her life's work has been about understanding why America's middle class is being hollowed out, and why families of color face an even rockier path to building a future."

Standing out from the crowd

Biden, the early frontrunner for the nomination, has a page on his website titled "Joe's Vision." The main points of his vision are rebuilding the middle class, making the U.S. respected abroad, and making sure "democracy includes everyone."

There are several paragraphs addressing issues like "Restoring the basic bargain for American workers," but no concrete policy proposals. Biden's campaign is several months younger than Warren's, but it is still far less thorough in describing what "Joe's Vision" is and how it would be implemented.

Buttigieg receives much attention from the press and has recently shot to the middle in early polls. At 37, he is the youngest candidate in the race, and would be the first openly gay president. But while many voters are attracted to Buttigieg, a polyglot Rhodes Scholar and veteran who emphasizes his Midwest roots, he's largely stayed away from detailed policy proposals.

Sanders' website has several pages outlining his major policies, like his signature promise to expand Medicare to cover all Americans and to pass a Green New Deal. Having spent several decades in politics advocating for democratic socialism, he often articulates a vision for broadly transforming the economy.

But many of Warren's policy proposals are more specific, even bordering on granular, as evidenced by her plan to combat high maternal mortality rates among black women and her step-by-step plan addressing student debt. On his website, meanwhile, Sanders says he would "substantially lower student debt" without saying specifically how.

Warren and Sanders have often been grouped together given their shared emphasis on expanding social services and their critique of the economic system. Some of her supporters are concerned that voters who may have been drawn to Warren will instead flock to Sanders, who has performed well in the polls and mounted a surprisingly strong race in 2016.

However, it is just as possible that potential Sanders supporters would eventually drift toward Warren, said Christina Reynolds, the vice president for communications at Emily's List, a group that supports Democratic women running for office.

"I think Elizabeth Warren draws some would-be supporters away from Bernie," Reynolds, whose group has not yet endorsed a 2020 presidential candidate, said. "I suspect some of their supporters are having a tough time deciding which one to support."

Sanders isn't the only candidate running on a platform similar, but less detailed, than Warren's. Harris and Sen. Cory Booker also support "Medicare for All," and voters who may support universal health care but are wary of Sanders' socialism could turn to any of them instead.

Women can face more intense scrutiny when running for president than men. But according to Kelly Dittmar, an associate research professor at the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, Warren's emphasis on policy could help her sidestep deeply-rooted stereotypes.

"Women candidates are likely to put out more policy plans because that's an area where they have historically been questioned," Dittmar said.

But putting out policy plans isn't enough. Women also must tackle the "likability" factor: If a woman is too wonky, she might be considered unapproachable, Dittmar said. But if she's too vague, voters might question why she is running. This issue is compounded for women of color in the race, like Harris, who must also battle the notion that the presidency is an office that should be held by white men.

Reynolds said Warren was not campaigning on policy alone, and did have the same kind of vision for the future for which male candidates have been praised.

"Elizabeth Warren has a lot of policy. She also has a vision that drives that policy," Reynolds said.

The electability problem

Reynolds also questioned why the idea of "electability" was used as a metric to judge any candidate, and particularly women.

"Literally our last two presidents, including Donald Trump, were viewed as unelectable almost until the day that they were elected," Reynolds said.

Still, polls have repeatedly shown that Democratic primary voters are thinking long and hard about electability, and many have their doubts that Warren could beat President Trump.

New Hampshire is a state where Massachusetts candidates like Warren typically do quite well, but a Suffolk University survey of Granite State Democrats released earlier this week had her in fourth place behind Biden, Sanders and Buttigieg. When asked why, nearly 1-in-5 non-Warren voters said the main reason they don't support her is because they doubt she can beat Mr. Trump.

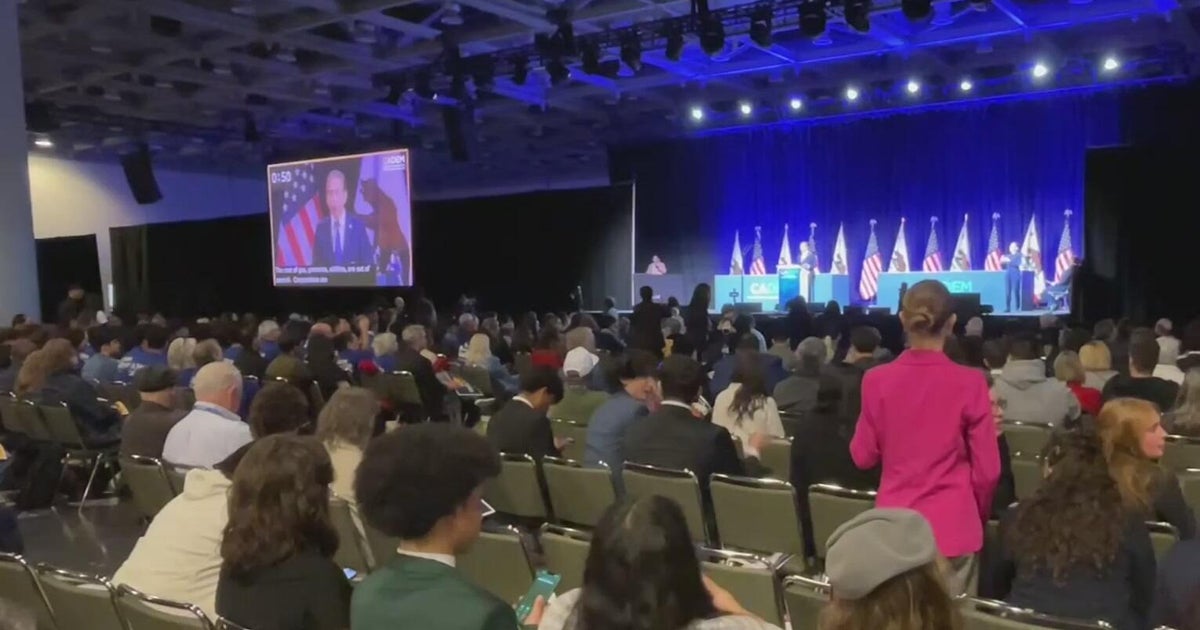

Warren challenged the concept of electability at the forum last week hosted by She the People, an organization which seeks to promote women of color in politics. When asked about Democrats who were anxious about nominating a woman after Clinton's 2016 defeat, Warren said voters needed to fight for the principles that matter to them.

"We've got a roomful of people here who weren't given anything. We have a roomful of people here who had to fight for what they believe in," Warren said, speaking to an audience largely composed of women of color.

"Are we going to show up for people that we didn't actually believe in because we were too afraid to do anything else? That's not who we are. That's not how we're going to do this."