Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes takes the stand in her criminal fraud trial

Fallen Silicon Valley star Elizabeth Holmes, accused of bamboozling investors and patients into believing that her startup Theranos had developed a blood-testing device that would reshape health care, took the witness stand Friday in her trial for criminal fraud.

The surprise decision to have Holmes testify so early came as a bombshell and carries considerable risk. Federal prosecutors, who rested their months-long case earlier on Friday, have made it clear that they're eager to grill Holmes under oath.

Prosecutors won't get that chance until Monday at the earliest, when the trial resumes. Prosecutors called 29 witnesses to support their contention that Holmes endangered patients' lives while also duping investors and customers about Theranos' technology. Among them was General James Mattis, a former U.S. defense secretary and former Theranos board member.

They also presented internal documents and sometimes salacious texts between Holmes and her former lover, Sunny Balwani, who also served as Theranos' chief operating officer. Through the prosecution's case, Holmes sat bolt upright in her chair, impassive even when one-time supporters testified to their misgivings about Theranos.

That combination of compelling testimony and documentary evidence apparently proved effective at convincing Holmes to tell her side of the story in court. Listening Friday were 10 men and four women on the jury that will ultimately decide her fate. If convicted, Holmes — now 37 and mother to a recently born son — could be sentenced to up to 20 years in prison.

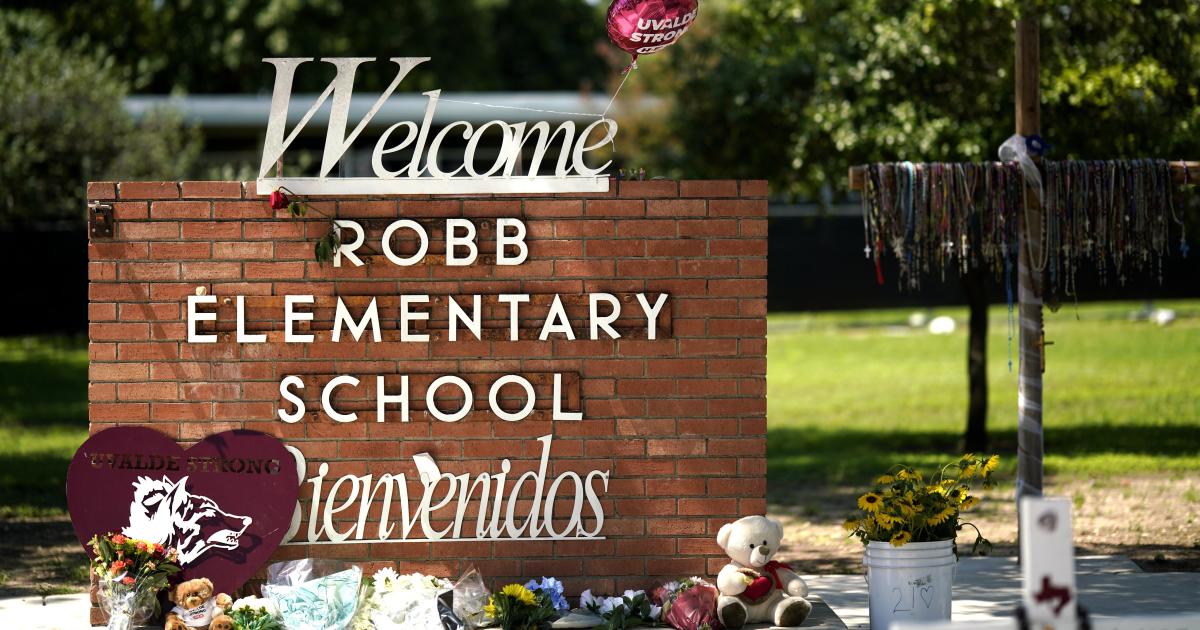

Shortly after 3 p.m. local time, Holmes walked slowly to the stand before a rapt courtroom filled with spectators and jurors, all wearing masks. She began her nearly hour-long testimony by recounting her early years as a student at Stanford University and her interest in disease detection, culminating in her decision to drop out of school at 19 and found the startup later known as Theranos.

As the company took shape, so did its vision. Ultimately Theranos developed a device it called the Edison that could allegedly scan for hundreds of health problems with a few drops of blood. Existing tests generally each require a vial of blood, making it both slow and impractical to run more than a handful of patient tests at a time.

Had it worked as promised, the Edison could have revolutionized health care by making it easier and cheaper to scan for early signs of disease and other health issues. Instead, jurors heard recordings of Holmes boasting to investors about purported breakthroughs that later proved to be untrue.

Witness testimony and other evidence presented in the trial strongly suggests that Holmes misrepresented purported deals with major pharmaceutical firms such as Pfizer and the U.S. military while also concealing recurring problems with the Edison.

But the Edison problems didn't become public knowledge until The Wall Street Journal published the first in a series of explosive articles in October 2015. An audit by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services confirmed those problems the following year.

By then, Holmes and Balwani had raised hundreds of millions of dollars from billionaire investors such as media mogul Rupert Murdoch and the Walton family of Walmart and struck deals with Walgreens and Safeway to conduct blood tests in their pharmacies. Those investments at one point valued Theranos at $9 billion, giving Holmes a $4.5 billion fortune — on paper — in 2014.

Evidence presented at the trial also revealed that Holmes had distributed financial projections calling for privately held Theranos to generate $140 million in revenue in 2014 and $990 million in revenue in 2015 while also turning a profit. A copy of Theranos' 2015 tax return presented as part of the trial evidence showed the company had revenues of less than $500,000 that year while reporting accumulated losses of $585 million.

Ellen Kreitzberg, a Santa Clara University law professor who has been attending the trial, said she thought the government had made a strong case.

"There's nothing sort of fancy or sexy about this testimony," she said. "The witnesses were very careful in their testimony. None of the witnesses seemed to harbor anger or a grudge against her. And so because of that, they were very powerful witnesses."

Other witnesses called by the government included former two Theranos lab directors who repeatedly warned Holmes that the blood-testing technology was wildly unreliable. Prosecutors also questioned two part-time lab directors, including Balwani's dermatologist, who spent only a few hours scrutinizing Theranos' blood-testing technology during late 2014 and most of 2015. As Holmes' lawyers noted, the part-time lab directors were allowed under government regulations.

Other key witnesses included former employees of Pfizer, former Safeway CEO Steve Burd and a litany of Theranos investors, including a representative for the family investment firm of Betsy DeVos, the former education secretary under President Donald Trump. The DeVos family wound up investing $100 million.