Voter fraud, suppression and partisanship: A look back at the 1876 election

With nine days to go before the United States decides on a choice for president, some Americans are just hoping the race goes smoothy — far smoother than the disputed 1876 election, as CBS News' Mo Rocca shows us.

As the hundredth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, 1876 was a banner year for America — a nationwide celebration with a full fifth of the country's population descending on Philadelphia for the centennial exposition. But beneath the revelry, there was a deep sense of unease.

"This was the depths of a pretty serious economic depression," Columbia University history professor Eric Foner said. "There was widespread unemployment. There were fairly violent labor strikes in parts of the country."

The year also held a presidential election, and all of these issues — plus the rampant corruption in the administration of outgoing President Ulysses S. Grant — would factor into the contest.

Republicans ran Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes, who according to historian Dustin McLochlin was not the most charismatic candidate.

McLochlin is the historian at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center Fremont, Ohio. He said Hayes "really exemplified that American tradition of the office seeks you, you don't seek it."

Hayes' service as a general during the Civil War was central to his identity, according to the center's executive director Christie Weininger.

"He saw firsthand the passions that were behind the sectionalism that caused the Civil War," Weininger said. "I think that was always in the back of his mind ... how do we make this country feel united again?"

Meanwhile, the Democrats were hungry to reclaim the White House, which they had not won in 20 years. Their candidate, New York Governor Samuel Tilden, was a bachelor lawyer who had made his name fighting big-city corruption.

Robert Yahner, who oversees New York City's National Arts Club — once Tilden's beautiful Gramercy Park mansion — said the former governor was known as "a bit lethargic."

"Quite frankly, a lot of people thought he was dull — dull but dedicated," Yahner said.

Professor Foner said neither candidate was exactly Mount Rushmore material.

"Both of them were basically mediocrities, politically," Foner said.

Still, voter turnout on November 7, 1876, remains the highest ever for a presidential election — 82% of eligible citizens cast a ballot.

"You had two political parties competing throughout the nation," Foner said, "with people very loyal to them."

On election night, Tilden was ahead in the popular vote by 260,000 votes.

"Hayes actually goes to bed believing Tilden had won," Hayes historian Dustin McLochlin said. "He actually has interviews with reporters saying, 'I've lost.' The Republican Party has to step in and tell him to stop saying that."

That was because Republican officials still saw a narrow path to victory for Hayes — as Foner explained, if Hayes would win Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina, where the results were not yet clear, he'd take the election by one electoral vote.

"They just issued a statement, 'Hayes has carried those states and is elected'," Foner said, referring to the Republicans.

He compared their move to the 2000 presidential election, where he said, "[George W.] Bush made an early claim of victory even though it was so divided and Gore never quite contested it properly."

And just like in the year 2000, America in 1876 woke up the morning after the election not knowing who had won. Back then, the inauguration was in early March, which meant the country had four months to figure out who would be its 19th president.

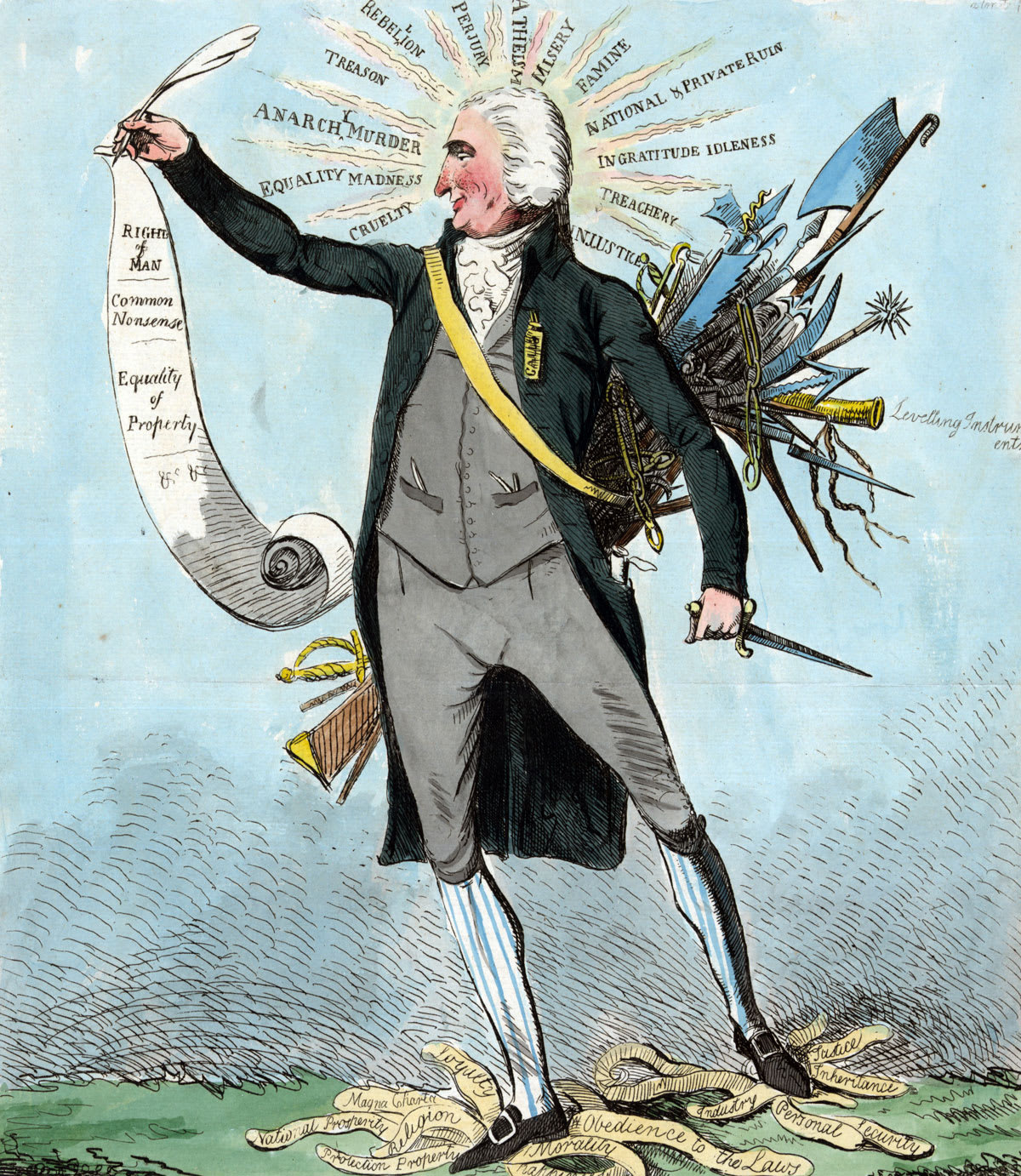

Massive voter fraud, Foner explained, only added to the confusion.

"This election was flawed from top to bottom," Foner said. "There was violence throughout the South against African American voters to try to… make it impossible for them to vote."

Black men — almost all of whom were Republican back then — had only recently won the right to vote. However, Southern Democrats were actively suppressing that right.

"If there had been a fair election in the South, there's no question, Hayes would have won by a large margin," Foner said.

But as the weeks dragged on, neither side was willing to concede.

"There were Democratic newspapers with headlines: 'March to Washington to Install Tilden as President.' There were Republicans saying, 'We're on the verge of another Civil War,'" Foner said.

McLochlin said the idea "Tilden or Blood" had been floated — meaning, if Tilden was not declared the victor there may be another war.

According to Foner, fears of dueling presidencies lingered as some key Democrats urged Tilden to "take the oath of office anyway" — which Tilden refused to do.

Foner said there was also a large group, particularly businessmen, who did not care who was elected and just wanted the matter settled.

Congress stood divided and the Constitution offered no clear direction for resolving the impasse. So in January of 1877, a 15-member electoral commission made up of eight Republicans and seven Democrats would determine which candidate won the disputed states.

"By some coincidence, all the electoral votes are allocated to Hayes by a vote of eight to seven in each case," Foner said. In other words, the commission voted strictly along party lines.

Tilden's camp cried foul. With the inauguration just days away and the nation on edge, representatives for both candidates met in Washington for secret negotiations.

"Ironically, they took place at Wormley House, a major hotel, which is owned by a Black man, [James] Wormley, probably the most well-to-do African American in the city of Washington at that time," Foner said.

It was ironic because the agreement forged there — known as the Compromise of 1877 — would have long-lasting repercussions for Black Americans in the South.

"The Democrats will not stop the inauguration of Hayes. They will accept Hayes as president. Hayes will end the remaining Reconstruction," Foner explained.

In other words, the Republicans got the White House, but the Democrats effectively regained control of the American South — which meant no more federal protection of the rights of recently freed African Americans.

"The Democrats promise they will respect the basic rights of the former slaves, which they do not do," Foner said.

Rutherford B. Hayes was certified as president on March 2, 1877. Samuel Tilden accepted the decision. Three days later, Hayes was inaugurated in a peaceful transition of power.

Hayes Presidential Center director Christie Weininger speculated that if either candidate had more of an "aggressive" or "intense" personality, and "wanted this presidency for very selfish reasons," the entire discussion would have been different.

According to Weininger, President Hayes today is remembered less for what he did during his single term in office than for an election that threatened to tear the country apart.

It's a story that seems to resonate with modern-day visitors to the center, Weininger said.

"They're very interested in how divisive the country was then," she said. "Somehow knowing that we've been there before and survived, I think, gives some comfort and some hope to people."

For more info:

- DC Public Library, Star Collection © Washington Post

- The People's Archive at DC Public Library

- American historian, Eric Foner

- Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museums

- National Arts Club

Story produced by Mary Lou Teel. Editor: George Pozderec.