Edward R. Murrow's "fake news" battle revealed in WWII memos

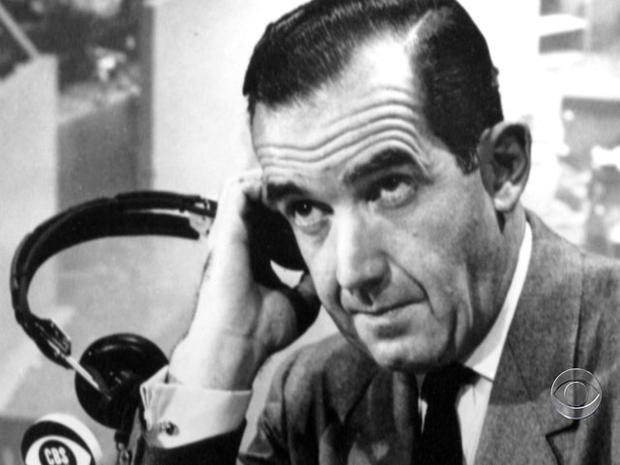

London — It was October 1940, Europe was being overrun by the Nazis, and Britain stood alone against a relentless German bombing campaign. Reporting it all over the radio waves to the American public, from his office across from the BBC, was legendary CBS News correspondent Edward R Murrow.

Murrow's reports were broadcast from the BBC studios, and they brought the war directly into American homes.

At the start of World War II, America was officially neutral. As CBS News contributor Simon Bates explains, Murrow's broadcasts are believed to have played a large part in shifting U.S. public opinion in favor of joining the conflict in support of the British.

There was a sizable isolationist movement in the U.S., and it accused Murrow and others of acting as a tool of the British government — and of not telling Americans the whole truth. You might call it a very early accusation of "fake news."

In 1939, Murrow explained the rules under which he was operating in a series of wartime memos, recently unearthed by the BBC.

"We are not permitted to divulge military information calculated to be of value to a possible enemy," he wrote. "Within these limits we are to have freedom of expression… there are certain matters of a military nature which we shall not be permitted to discuss; it does not mean that anyone is telling us what to say."

But the attacks on his integrity from back home irritated Murrow, and on Oct. 2, 1940, Roger Eckersley, the Head of the BBC's American Liaison Section, wrote a memo to his bosses with a bold proposal from the CBS News correspondent:

"Murrow tells me that there is a large body of opinion among American listeners that there is still a lot of unnecessary censorship in regard to the news and that they never know whether they are really hearing the truth or not. He wants to offset this once and for all and has put up a suggestion to me of doing a completely uncensored talk... he would not broadcast it if a line was altered... In my opinion there is something in it if it makes the American public realize that censorship here is done on really reasonable grounds," wrote Eckersley.

The idea certainly came as a shock to the censors at Britain's Ministry of Information, which stopped the proposed Murrow broadcast. Murrow was furious, saying that the bureaucrat's memo informing him of the decision would "occupy a privileged position in my file of documents reflecting the prostitution of the English language in the service of compromise and obscurity. It really is a classic and I am grateful for it... and I thought there was a shortage of paper."

Eckersley wrote back to Murrow:

"My dear Ed, I was tickled to death by your letter of 23rd October. Yes, do keep the note; it may be a valuable contribution of any history which is written 100 years hence entitled 'How compromise won the war — or not.'"

Murrow's proposal — to broadcast an uncensored report — was never raised again. A year later, in 1941, he was about to sail for a break in America, when he wrote a warm letter to his friends at the BBC:

"This is written from Bristol. Ain't seen a censor since I got in... Purpose of this epistle, which if carried to sufficient length would reek of pusillanimous high-mindedness, is merely to say that I have occasionally cursed you, and invariably enjoyed working with you... If the 'herrenvolk' come again before I return, I hope that all our 'censors' may be spared."

Night after night Murrow drove around the streets of London at great personal risk as the German bombs fell. His friends called him the "iron man of the blitz," relying on a mixture of adrenaline, black coffee and cigarettes.

The pressure took its toll, on his health and on his wife Janet.

Bates notes that Murrow never did broadcast an uncensored talk from his post in London, and perhaps he didn't need to.