If "the protocols work," how did Dallas nurse get Ebola?

When the first U.S. Ebola patient turned up at a Dallas hospital late last month, public health officials were quick to reassure the public that the health care system was prepared to handle it and prevent the deadly disease from spreading.

"We are stopping Ebola in its tracks in this country," Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said on Sept. 30, after Dallas patient Thomas Eric Duncan's Ebola test came back positive. "We can do that because of two things: strong infection control that stops the spread of Ebola in health care; and strong core public health functions."

But news that a nurse who treated Duncan became infected in the process has cast doubt on whether those safety precautions were good enough or were properly followed. The nurse at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital -- identified Monday as Nina Pham -- was wearing full protective gear when she treated Duncan, but somehow got infected anyway. Frieden said Sunday that the CDC was conducting an investigation into what went wrong, to try to prevent it from happening again.

"It is deeply concerning that this infection occurred," Frieden acknowledged. "We don't know what occurred... but at some point there was a breach in protocol and that breach in protocol resulted in this infection."

The reality is, even when health care workers know the proper steps, small -- but potentially deadly -- lapses can still happen.

"It's hard to stick to the protocol 100 percent of the time when you're responding to emergencies; you get lax," Dr. Dalilah Restrepo, an infectious diseases specialist at Mount Sinai Roosevelt and Mount Sinai St. Luke's in New York City, told CBS News in an interview last week.

The protocol for dealing with Ebola governs the steps hospitals and health care workers take to isolate an Ebola patient and the protective gear they wear to avoid infection.

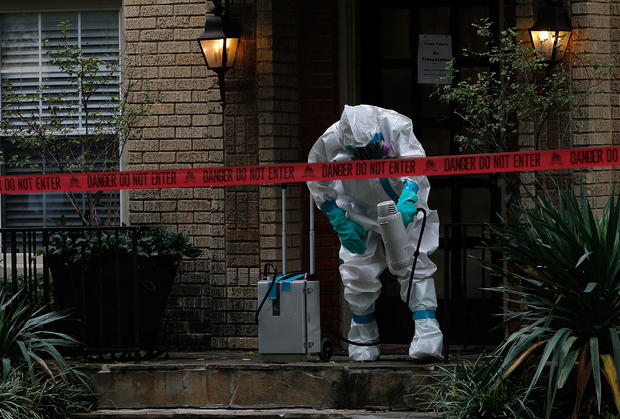

Personal protective equipment -- the head to toe "spacesuit" gear -- is impervious to the infectious bodily fluids that can spread Ebola from person to person. But for health care workers, taking off contaminated gear without infecting themselves is tricky and requires training and practice.

"In taking off equipment, we identify this as a major area for risk," Frieden said. "When you have gone into contaminated gloves, masks or other things, to remove those without risk of contaminated material touching you and being then on your clothes or face or skin and leading to an infection is critically important and not easy to do right."

Restrepo echoed concern about the hazards involved in safely removing protective gear. "We've seen in the removal process there's always a risk for infection," she said.

The best practice, she explained, is to have someone trained in infectious disease control responsible for helping a doctor or nurse remove their protective gear every time they leave a patient's room. "It's pretty much from the ground up. Booties come off first," she said. The priority is to keep contamination away from the eyes, nose and mouth, the primary means of transmission.

The CDC said Sunday it is reevaluating the protocols for using protective gear.

Officials from the CDC have also been interviewing the infected nurse for clues as to how, where and when the slip-up may have happened. But she "has not been able to identify a specific breach," Frieden said.

A similar, unexplained failure occurred recently at a hospital in Spain, where a nursing assistant was diagnosed last week with the Ebola virus. She became infected while caring for a missionary priest who contracted Ebola in Sierra Leone and who later died. The woman, like the nurse in Dallas, was believed to be complying with safety protocols.

In addition to the risk of possible exposure when removing protective gear, Frieden said investigators in Dallas would focus on two other areas of treatment that he called "very unusual": the fact that Duncan received kidney dialysis and respiratory intubation during the final days before he died on Oct. 8.

CBS News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jon LaPook notes that both procedures could potentially involve exposure to the patient's bodily fluids. "We know that Mr. Duncan got dialysis. He also got a breathing tube inserted into his lungs. And those are procedures in which there is a danger of contamination of health care workers."

Those high-risk procedures were undertaken "as a desperate measure to try to save [Duncan's] life," Frieden said, adding that he was unaware of any prior Ebola patient receiving either of those treatments.

While this troubling case of transmission remains unexplained, Frieden still insists that "the protocols work." He notes that these practices are based on decades of experience caring for patients with Ebola in Africa, where most previous outbreaks have been stopped after only a handful of cases.

"The bottom line is we know how Ebola spreads. We know how to stop it from spreading. But it does reemphasize how meticulous we have to be," Frieden said. "Even a single lapse or breach, inadvertent, can result in infection."