Ear grown under woman's forearm gets transplanted

Johns Hopkins University Hospital surgeons have successfully transplanted a new ear on a woman who lost one due to an unusually aggressive form of skin cancer.

The procedure was no ordinary transplant - doctors had to build her ear using cartilage pulled from other parts of her body, then surgically implanted it on her arm to allow skin growth before re-attaching it to her head.

Sherrie Walter, a 42-year-old retail sales manager from Bel Air, Md., underwent the painstaking series of operations that began in January 2011 and ended with a new ear by September 2012. She had been diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma, the most common type of skin cancer in the United States. Many types of basal cell carcinomas are slow-growing, however this particular case was aggressive.

She was first diagnosed in 2008 and had intense radiation therapy and regular biopsies, but in 2010 she saw some blood in her left ear and learned her cancer returned. The cancer had also spread to nearby parts of her skull and salivary glands, so she needed her ear and other surrounding head, neck, gland, lymph and skull tissues removed to save her life.

"When my doctors told me reconstruction was possible, I thought it was too good to be true; it sounded like science fiction," Walter said in a hospital press release. "Just learning that reconstructing my ear was doable gave me sufficient physical and emotional strength, as well as the confidence I needed to go through with the surgeries."

Traditional reconstructive ear surgeries employ a plastic prosthetic ear, but Walter's cancer surgery removed the necessary skull bone structure and stretchable skin from her face and neck required for such an operation.

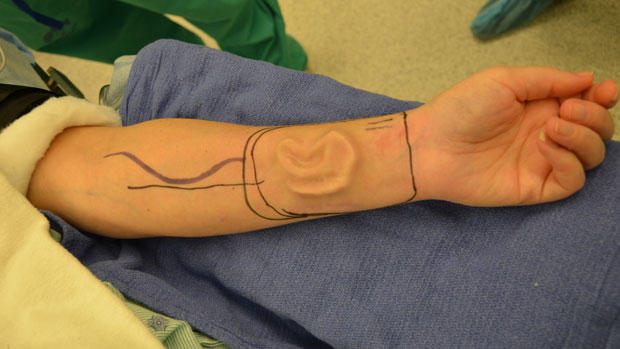

So in what's considered one of the most complicated ear reconstructions ever, doctors removed pieces of her rib cartilage to assemble the new ear structure. The skinless structure was then surgically implanted under her forearm skin for four months, to allow it to stretch and grow skin and be nourished by the forearm's blood vessels.

"We started making jokes just to try to get used to it and I was like, 'Can you hear me? Can you hear me?' Sherrie's husband Damien said to CBS Baltimore.

Walter's surgeon Dr. Patrick Byrne, associate professor in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, then surgically removed the ear from Walter's arm, and connected it to blood vessels in the head and began to sculpt it to look like a functioning ear. A special hearing aid allows her to hear from her left side.

"I thought of this exact strategy many years before and really was looking for the right patient to try it on," Byrne told CBS Baltimore.

She still has two more minor surgeries to go, but doctors hope the ear will last for decades.

"It's a cliche but use the sunscreen and if you are not sure about something, get it checked because that's what I didn't do," Walters said.