Drop in apprehensions along the US-Mexico border continued in December

Washington — December marked the seventh consecutive monthly drop in apprehensions along the U.S.-Mexico border, according to new government figures, with U.S. officials apprehending nearly 33,000 migrants — a sharp drop from the 13-year monthly high of 133,000 arrests last May.

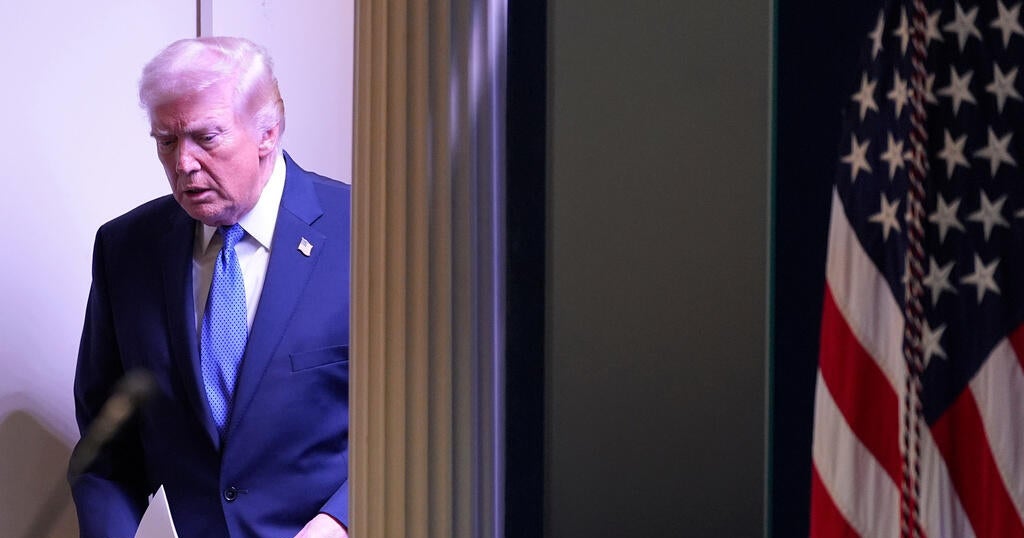

The Trump administration attributes the decline in apprehensions to controversial policies it rolled out in the past 12 months to restrict asylum at the southern border and deter migrants from making the journey to the U.S. The December apprehension figures — the lowest since July 2018 — suggest that the Trump administration continues to stem the flow of Central American families, who journeyed to the southern border in record numbers last spring, overwhelming officials and already crowded detention facilities.

Border Patrol apprehended about 8,600 families with children and more than 3,200 unaccompanied minors last month. The rest of the apprehensions, about 21,000, were of single adults. In addition to the apprehensions, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers turned back nearly 8,000 migrants.

CBP officials said the administration's restrictive policies have collectively conveyed to migrants considering trekking north that "catch and release is essentially over." Long derided by President Trump and immigration hardliners, "catch and release" is a term used by some to describe the practice of releasing migrants to await immigration hearings outside of a detention center because of legal protections for families and children, as well as detention capacity.

"Don't give away your life savings to smugglers," a CBP official said during a call with reporters Thursday, describing one of the messages the administration wants to send to would-be migrants.

In 2019, immigration judges decided more than 67,000 asylum cases, a record high, according to data from Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). Nearly 20,000 migrants were granted asylum last year, but more than 46,000 were denied the protection or other forms of relief from deportation.

Through a series of experimental programs implemented in 2019, the Trump administration has gained the power to restrict or shut off asylum for most types of migrants who ask for protection at the southern border. More than 56,000 asylum-seekers from Latin American have been required by the U.S. to wait in Mexico for the duration of the immigration court proceedings. Many of those returned under the "Remain in Mexico" program face squalid conditions in overcrowded shelters and makeshift encampments, and most are unable to find lawyers to help them with their asylum cases.

Officials have continued to "meter" migrants, limiting the daily number of would-be asylum-seekers who can express fear of persecution at U.S. ports of entry along the southern border.

Programs to expedite the deportation of migrants seeking protection, including those rendered ineligible for asylum under a sweeping regulation, have expanded in recent weeks. The U.S. has also sent nearly 100 asylum-seekers from Honduras and El Salvador to Guatemala, denying them access to America's asylum system and requiring them to choose between seeking refuge in the Central American country or returning home.

Other similar deals with the governments of Honduras and El Salvador would allow the U.S. to reroute certain asylum-seekers there, but they have not been implemented yet.

According to the Guatemalan government's migration institute, 97 asylum-seekers, all of them from El Salvador and Honduras, have been sent by the U.S. to Guatemala under the agreement between both countries. The agency is currently processing only one asylum case, since the vast majority of the migrants have requested help returning to their home countries.

A recent plan to send Mexican asylum-seekers to Guatemala has been met with objections from both countries' governments. On Thursday, CBP officials conceded that they continue to see an increase in Mexican families seeking refuge in the U.S. — a problematic trend since migrants from Mexico can't be placed in the "Remain in Mexico" program or denied access to asylum under a regulation unveiled in the summer.