What Trump can learn from Reagan on tax reform

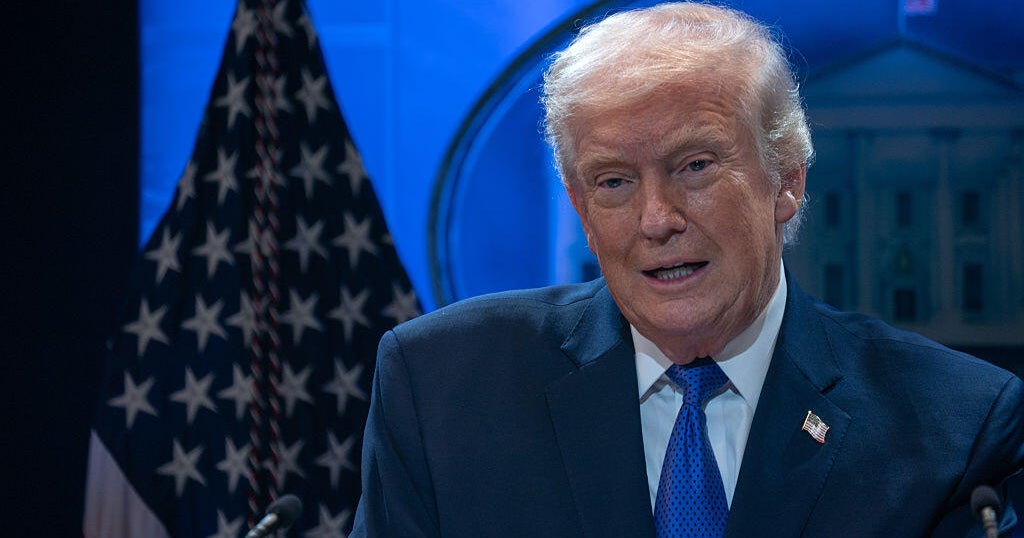

President Donald Trump doesn’t invoke Ronald Reagan as much as many Republicans do. But with revamping the tax code a major priority of the Trump White House, it might help him to study how Reagan delivered the last major tax overhaul three decades ago.

Reagan’s success on tax reform in 1986 came despite many twists and turns, and more than a few times the entire enterprise appeared doomed. So it’s instructive to compare this year’s climate for a tax overhaul with the situation back then.

Tax reform is a taller order to replicate in 2017. Today’s political scene is much more divided, almost to the point of open partisan warfare. In his address to Congress Tuesday night, Mr. Trump tried to put the argumentative tone of his first month in power behind him and called for a bipartisan approach to passing legislation. That harks back to Reagan’s sunnier view, but it remains to be seen whether Mr. Trump can continue down that optimistic and inclusive path.

There are other differences. Mr. Trump seems less concerned about running red ink as a result of the tax revamp, whereas Reagan insisted that the outcome be “revenue neutral,” meaning it wouldn’t add to the government deficit. That solidified Reagan’s GOP base in Congress.

And Mr. Trump’s tax plan is linked to the fate of other matters, like what happens to Obamacare. Reagan turned to tax reform in the sixth year of his presidency, after he had enacted many of his policy goals, thus avoiding distractions. Mr. Trump’s glut of plans, from cracking down on immigration to Obamacare repeal, provide plenty of distractions.

One constant then and now, however, is the army of lobbyists who, armed with campaign contributions that smooth their access to Capitol Hill, ferociously fight to retain tax breaks favoring their clients.

In “Showdown at Gucci Gulch,” a masterful study of the 1986 tax reform bill’s passage, two Wall Street Journal reporters recounted how swarms of lobbyists sought to influence lawmakers. As authors Alan Murray (now chief content officer of Time Inc. and editor of Fortune magazine) and Jeffery Birnbaum (who these days works for a lobbying firm himself, BGR Group) wrote, the triumph of tax reform over these well-dressed -- and well-shod, hence the Gucci reference -- advocates was a minor miracle.

The byword for Reagan and his allies in Congress was to simplify the code and eliminate many tax breaks. The number of tax brackets, for instance, was pruned back to two from 14. But over the years, like an untended shrub, the number of categories proliferated again (seven now), and a profusion of new tax breaks sprouted.

Among Republicans, the touchstone for tax reform is the framework put together by House Speaker Paul Ryan, R-Wisconsin. During last year’s election campaign, Mr. Trump issued his own version, which borrowed heavily from Ryan’s. The administration lately has released broad outlines for its plan and is working on details.

Thus far, they have a lot of common elements. Both want sweeping tax cuts for individuals and businesses, as well as to simplify the code by, among other things, reducing the number of brackets to three.

In light of this, let’s look at what happened under Reagan in 1986 and what Mr. Trump is dealing with:

Reagan went bipartisan. Then as now, Republicans sought to lower taxes, but the well-off benefited the most, and the Democrats have decried this disparity. But Reagan was able to win over Democrats, who controlled the House of Representatives but not the Senate in 1986, by touting the appeal of other parts of the legislation, like expanding the standard deduction.

Ending loopholes that favored the rich was another selling point to Democrats. Some of the more contentious original features were pared away, such as a proposal to end the deductibility of mortgage interest.

While Reagan wasn’t involved in many of the intricacies of the bill -- he, like Mr. Trump, was more of a big-picture guy -- his amiable relations with Capitol Hill helped smooth enactment. Reagan regularly got together for cocktails with House Speaker Thomas “Tip” O’Neill, a Democrat from Massachusetts. Republicans and Democrats in Congress had cordial relations that allowed them to negotiate more easily. In the Senate, a so-called “Gang of Seven” Republicans and Democrats steered the bill.

But the parties have grown much further apart ideologically over the past quarter century, according to political science studies. When Barack Obama was president, congressional Republicans made a point of torpedoing many of his initiatives. With Mr. Trump in office, the Democrats vow to be similarly obstructionist.

Mr. Trump’s combative style has provoked tensions with Democrats, certainly, but also among some of his fellow Republicans. Although Speaker Ryan is vital to winning enactment of Mr. Trump’s program, the president in the past has called him a “loser” and “very weak and ineffective.” That, of course, was during the election, and the GOP leadership on the Hill now portrays itself as behind the president. Still, it remains to be seen how they’ll work together in practice.

“There’s tremendous antipathy toward Trump,” said economist Gary Shilling, who advised the Reagan administration in the 1980s. “Reagan was the antithesis of Trump.”

Reagan was mindful of the budget impact. An avowed enemy of deficit financing, Reagan said he would veto the tax bill if it lowered or raised tax revenue. To that end, the 1986 measure reduced individual tax rates and hiked payments for corporations.

The Reagan administration did manage to whittle down deficits. Reagan was a believer in supply-side economics, which contends that lower taxes will spur growth and yield a bumper crop of extra tax revenue. How that worked out during his tenure is open to debate: After an initial set of tax cuts in 1981 soon after taking office, Reagan’s deficits as a share of GDP deepened to 5.7 percent in the beginning of his presidency, albeit due to a recession.

But then the deficits shrank after the 1986 overhaul, from 4.8 percent in that year to 3.1 percent in 1987 to 2.9 percent in 1988. Indeed, other factors may have been at work in Reagan’s last years in office, boosting the economy and generating more tax revenue, such as a squelching of rampant inflation by the Federal Reserve and an end to oil disruptions from the Middle East. Nonetheless, the general movement in his two terms was toward smaller deficits.

Under the Trump plan, deficits, and the national debt they feed, likely would balloon even more, some budget experts predict. That’s the verdict of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Thanks to entitlement programs, chiefly Social Security and Medicare, the result of an aging population, federal debt held by the public, now 77 percent of GDP, would climb to 106 percent by 2035, the group estimates.

Mr. Trump has opposed making any changes to entitlements benefiting older Americans.The reason: He had promised over-65 voters he wouldn’t -- a politically wise move, even if debatable from a long-term economic standpoint.

So adding new spending to this already enormous pile of debt obviously would accelerate the process. And that would trigger opposition from Capitol Hill’s Republican budget hawks. Speaker Ryan has a budget-hawk pedigree, so it remains to be seen whether this will develop into a flashpoint between him and the White House when it comes to the horsetrading of legislating.

To keep his plan from busting the budget, Ryan is backing a border adjustment tax, which would impose levies on imports, while charging exports nothing. He figures this would offset any revenue lost from tax reform. Mr. Trump is dubious of this notion, and import-dependent industries side with the president, who believes lowering taxes will touch off an economic boom and pay for the tax stimulus and other plans.

Reagan lasered in on taxes, with minimal distractions. By 1986, Reagan already had achieved his first round of tax reductions (in 1981), pared back regulations and bolstered the military. So he had a clear path to tax reform with few competing demands before Congress. As Bank of America Merrill Lynch recently indicated: “Compared to current proposals, the ‘86 reform involved a relatively simple trade-off of lower tax rates for reduced loopholes.”

In 2017, tax reform is more complex than Rubik’s Cube. So many other interconnected issues have a bearing on the tax question: repeal and replacement of Obamacare (which Mr. Trump says must happen before anything else), infrastructure build-outs, domestic spending cuts and military expansion. If the administration manages to limit Medicaid subsidies from Obamacare recipients, for instance, that could free money for use elsewhere. That’s no sure thing, however.

The Republican consensus in 2017 is to promote “pro-growth” provisions, such as pushing down corporate tax rates, in a bid to make U.S. companies more competitive with foreign rivals, which benefit from smaller tax bites. The president and the speaker both want to lower the top corporate rate from its current 35 percent to either 15 percent (Mr. Trump) or 20 percent (Ryan).

But they’re apparently parting company on the border tax, which has generated heated resistance from retailers and other industries that depend upon foreign-made goods. Ryan is in favor of the tax, while the president has called it “too complicated.”

The debate on the border tax issue prompted UBS Financial Services to wonder in a recent research note, whether it was a “bridge too far.” The same could be said for the ambitious tax reform question as a whole. The challenge for Mr. Trump is to show that, despite all the impediments, he can bring tax reform home, just like Reagan did.