DOJ takes regulatory step towards bump stock ban

The Trump administration announced Saturday it has taken the first step in the regulatory process to ban bump stocks, likely setting the stage for long legal battles with gun manufacturers while the trigger devices remain on the market.

The move was expected after President Trump ordered the Justice Department to work toward a ban following the shooting deaths of 17 people at a Florida high school in February. Bump stocks, which enable guns to fire like automatic weapons, were not used in that attack — they were used in last year's Las Vegas massacre — but have since become a focal point in the gun control debate.

The Justice Department's regulation would classify the hardware as a machine gun banned under federal law. That would reverse a 2010 decision by the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives that found bump stocks did not amount to machine guns and could not be regulated unless Congress amended existing firearms law or passed a new one.

A reversal of the department's earlier evaluation could be seen as an admission that it was legally flawed, which manufacturers could seize on in court. Even as the Trump administration moves toward banning the devices, some ATF officials believe it lacks the authority to do so.

But any congressional effort to create new gun control laws would need support from the pro-gun Republican majority. A bid to ban the accessory fizzled last year, even as lawmakers expressed openness to the idea after nearly 60 people were gunned down in Las Vegas.

Some states have sought their own restrictions in light of the inaction. A ban on bump stocks was part of a far-reaching school safety bill signed by Florida Gov. Rick Scott, a Republican, on Friday that was immediately met with a lawsuit by the National Rifle Association. The powerful group has said it supports ATF regulations on the accessory but opposes any legislation that would do that same. The NRA did not immediately return calls for comment Saturday.

Calls mounted for a bump stock ban after the Las Vegas shooting, and the Justice Department said in December it would again review whether they can be prohibited under federal law. Trump told officials to expedite the review, which yielded more than 100,000 comments from the public and the firearms industry. Many of the comments came from gun owners angry over any attempt to regulate the accessory, a move they view as a slippery slope toward outlawing guns altogether.

The proposal still needs the approval of the Office of Management and Budget.

But other concerns about holes in gun security persist.

Recent mass shootings have spurred Congress to try to improve the nation's gun background check system that has failed on numerous occasions to keep weapons out of the hands of dangerous people. Mr. Trump has called for "strong" background checks.

The problem with the legislation, experts say, is that it only works if federal agencies, the military, states, courts and local law enforcement do a better job of sharing information with the background check system — and they have a poor track record in doing so. Some of the nation's most horrific mass shootings have revealed major holes in the database reporting system, including massacres at Virginia Tech in 2007 and at a Texas church last year.

Despite the failures, many states still aren't meeting key benchmarks with their background check reporting that enable them to receive federal grants similar to what's being proposed in the current legislation.

"It's a completely haphazard system — sometimes it works; sometimes it doesn't," said Georgetown University law professor Larry Gostin. "When you're talking about school children's lives, rolling the dice isn't good enough."

In theory, the FBI's background check database, tapped by gun dealers during a sale, should have a definitive list of people who are prohibited from having guns — people who have been convicted of crimes, committed to mental institutions, received dishonorable discharges or are addicted to drugs.

But in practice, the database is incomplete.

It's up to local police, sheriff's offices, the military, federal and state courts, Indian tribes and in some places, hospitals and treatment providers, to send criminal or mental health records to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, or NICS, but some don't always do so, or may not send them in a timely fashion.

Some agencies don't know what to send; states often lack funds needed to ensure someone handles the data; no system of audits exists to find out who's not reporting; and some states lack the political will to set up a functioning and efficient reporting process, experts said.

"The system is riddled with opportunities for human error," said Kristin Brown, co-president of the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.

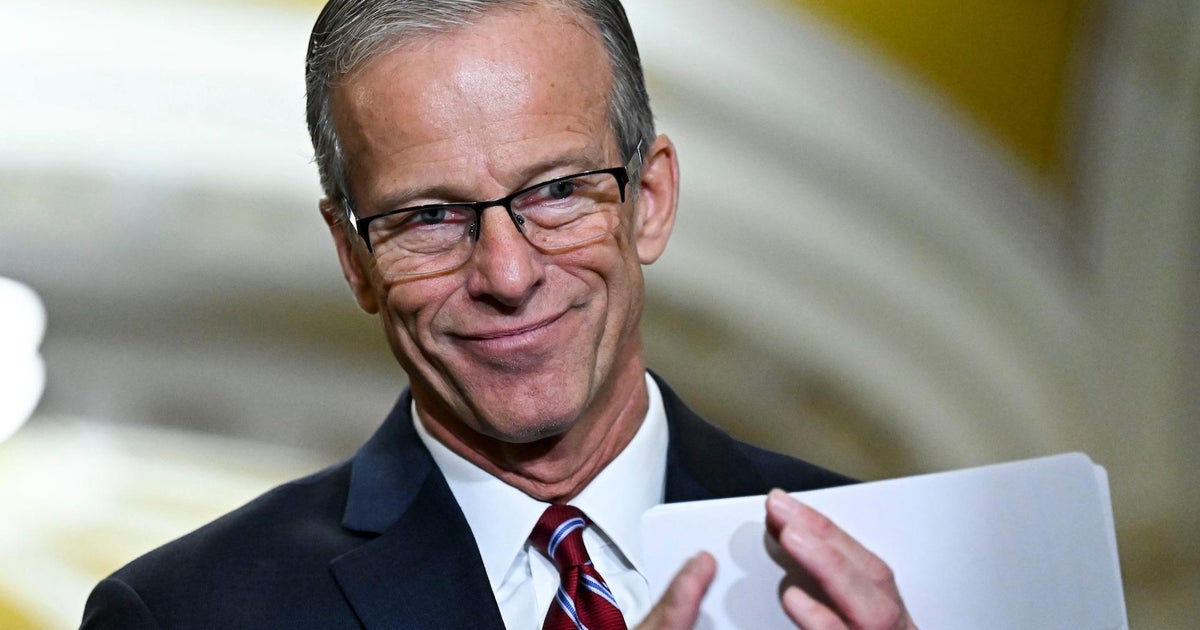

A proposal in Congress seeks to establish a structured system for federal agencies to send records to the NICS database. Sen. John Cornyn of Texas says the legislation — often referred to as "Fix NICS" — will save lives.

"We should start with what's achievable and what will actually save lives, and that describes the 'Fix NICS' bill. It will help prevent dangerous individuals with criminal convictions and a history of mental illness from buying firearms," the Republican said.

Often left out of the debate in Washington is the fact that similar legislation passed after the 2007 Virginia Tech massacre, but many records are still not being sent to the database.

The Justice Department even set up a new grant program that offered states help with their reporting system, but many didn't even bother to apply. In 2016, only 19 states and one tribe received funds totaling $15 million. The number of states currently participating is 31.