Document points to Nixon in My Lai cover-up attempt

By: Evie Salomon

This past week marked the 46th anniversary of the My Lai massacre, in which 504 unarmed Vietnamese civilians were massacred by U.S. troops in 1968. It's one of the most shameful chapters in American military history, and now documents held at the Nixon Presidential Library paint a disturbing picture of what happened inside the Nixon administration after news of the massacre broke.

The documents, mostly hand-written notes from Nixon's meetings with his chief of staff H.R. "Bob" Haldeman, lead some historians to conclude that President Richard Nixon was behind the attempt to sabotage the My Lai trials and cover up what was becoming a public-relations disaster for his administration.

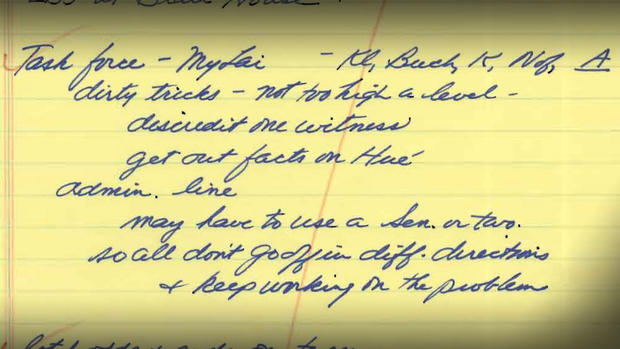

One document, scribbled by Haldeman during his Dec. 1, 1969, meeting with Nixon, reads like a threatening to-do list under the headline "Task force - My Lai." Haldeman wrote "dirty tricks" (with the clarification that those tricks be "not too high a level") and "discredit one witness," in order to "keep working on the problem."

The question is, was anyone actually on the receiving end of those "dirty tricks" in Haldeman's My Lai action plan? According to Trent Angers, author of newly updated book "The Forgotten Hero of My Lai," Nixon's targets were the star witnesses of the My Lai trials: pilot Hugh Thompson and gunner Larry Colburn. They were the two surviving members of a U.S. helicopter crew that was flying a reconnaissance mission over the South Vietnam village of My Lai when they saw the massacre in progress that March day in 1968.

If not for the actions of the helicopter crew, the death count at My Lai could have been far higher. Thompson and Colburn were so horrified by the sight of American soldiers slaughtering unarmed civilians, they put their own lives at risk to try to stop it, even saving a boy from a corpse-filled ditch and delivering him to the hospital.

Mike Wallace told the helicopter crew's story in the gut-wrenching 60 Minutes segment called "Back to My Lai" (posted in the video player above), which was first broadcast in 1998. That same year, the U.S. military officially honored the crew's actions in My Lai. Not present was the crew's third crew member, Glenn Andreotta, who was shot and killed in action three weeks after the massacre. It had taken 30 years for the U.S. government to recognize the three men.

But when Thompson and Colburn first returned home after Vietnam, it was a much different story. They weren't received as heroes, but as traitors.

Thompson testified about the massacre in the U.S. government's military trials, but according to author Trent Angers, two Congressmen who were working in concert with Nixon, managed to seal that testimony in order to damage the cases against the culprits of My Lai. Whether it was one of the "dirty tricks" Nixon prescribed in Haldeman's 1969 meeting note is a matter of debate for historians.

James Rife, a senior historian at History Associates Inc., helped author Trent Angers find the Haldeman meeting notes, which are described in detail in "The Forgotten Hero of My Lai."

"I would not characterize [the "dirty tricks" note] as a smoking gun, but it's pretty strong," Rife says. "I don't think we'll ever find an actual document that can make the absolute final link between Nixon and Hugh Thompson."

According to historian Ken Hughes, it's the historical context that makes for a convincing argument. He calls My Lai "a political threat to Nixon," and points out that a substantial part of Nixon's support base refused to believe that killing civilians in a war zone was a crime. According to Hughes, Nixon's approval rating dropped by 10 points after Lieutenant William Calley received a life sentence for murdering civilians at My Lai.

Nixon intervened, and Lt. Calley's sentence was reduced. He was paroled after only three years under house arrest.

The gunner on Hugh Thompson's chopper, Larry Colburn, told 60 Minutes Overtime that he and Thompson learned of the Nixon meeting notes long ago. (The documents were made available to the public in 1987.) Aside from a brief mention in the 1992 book "Four Hours in My Lai" by Michael Bilton and Kevin Sim, the "dirty tricks" note has received almost no attention from journalists or historians over the years. Colburn says he's surprised it wasn't a bigger story.

"There was no reaction at all," Colburn says. "I was amazed. I thought, 'Are you kidding me?'"

Colburn and Thompson remained friends throughout the years, speaking regularly on the phone and traveling back to My Lai together in 2001. On that trip, Colburn says they were reunited with the 8-year-old child they saved from the ditch.

Thompson died in 2006, and Colburn says he was in the room with him during his final moments. With his friend gone, Colburn says he feels an obligation to carry the torch, and speak publicly about what happened in My Lai that day. But he misses having Thompson at his side.

"There were times you start thinking, 'Why are so many people against what we did? What we did was morally correct-- why don't they understand?' It was always nice to have one other person who did understand," says Colburn. "We were therapeutic for each other."

Although Colburn says he has no regrets about his own actions at My Lai, he has doubts that the U.S. military took the lessons of the massacre to heart.

"The U.S. claims to be concerned with collateral damage with civilians that are caught up in war zones, but I don't believe that," Colburn says. "That's lip service."

When Colburn considers the actions of the U.S. in military conflicts of recent years, he says: "It makes me wonder about 46 years of testimony, and interview, books and lectures. I know it's had some impact, but on a larger scale, does it really matter what we say?"

The 60 Minutes segment "Back to My Lai," produced by Tom Anderson and reported by Mike Wallace, aired March 29, 1998.

Correction: A previous version of this article erroneously referred to the child that was saved by Hugh Thompson and Larry Colburn as "wounded."