What is a discharge petition? How House lawmakers are trying to force a vote on foreign aid

Washington — The Senate approved a $95 billion foreign aid package last month, with a bipartisan group of senators backing the bill that includes assistance to Ukraine and Israel. But House Speaker Mike Johnson has opposed bringing the measure to the floor, resisting calls from President Biden and Democratic leaders.

Accordingly, House Democrats are making a push to force a vote in the chamber through a rarely successful legislative maneuver known as a discharge petition that allows a majority of members to bring a bill to the floor. The discharge petition went live this week, garnering around 170 signatures in the first 24 hours.

"If the speaker is not going to lead, if he is not going to follow us, he should get out of the way and we will do it ourselves with a discharge petition," Rep. Abigail Spanberger, a Virginia Democrat, said Wednesday.

But whether the petition can gain the support of a majority of the chamber remains to be seen. Here are the basics on how a discharge petition could work:

What is a discharge petition, and how does it work?

In the House, the speaker typically works with leaders to set the agenda, and decides which bills or resolutions will or won't get a vote. Most legislation originates in committees, which then vote to send bills to the floor for final approval.

But lawmakers can "discharge" legislation that's been sitting in committee if 218 members, a majority of the lower chamber, sign a petition to do so, effectively bypassing the speaker to bring a bill before the full House for a vote.

"Discharge is generally the only procedure by which Members can secure consideration of a measure without cooperation from the committee of referral, or the majority party leadership and the Committee on Rules," a Congressional Research Service report from 2023 said. "For this reason, discharge is designed to be difficult to accomplish and has rarely been used successfully."

A House rule dating back to 1931 outlines the process. Any member can file a discharge petition with the House clerk, who then makes it available in a "convenient place" for members to sign.

A waiting period of seven legislative days kicks off once the petition gains the signatures of a majority of the chamber. After that, a member who has signed the petition can notify leadership that they'll bring the discharge motion on the floor.

The speaker must then designate a time for the motion to be considered within two legislative days. If a majority approves it, the House then moves to consider the underlying measure.

Discharge petitions don't often succeed, since a petition brought by the minority party requires members of the majority to buck their party leaders. In recent years, members have tried to use discharge petitions to raise the debt ceiling, increase the federal minimum wage and address other issues. In 2015, several dozen House Republicans bucked party leaders to join with Democrats, who were in the minority, to reauthorize the Export-Import Bank. Before that, a discharge petition hadn't succeeded since 2002.

The waiting periods, and the fact that garnering enough signatures can take weeks, often renders the maneuver futile for time-sensitive legislation. And a discharge petition can only be brought to the floor on specific days, further complicating its use.

Getting members of the majority party to sign on remains the biggest hurdle for a discharge petition, according to Matt Glassman, a senior fellow at the Government Affairs Institute at Georgetown University. While there may be a sizable group of Republicans willing to vote for the bill should it come to the floor, they may not be willing to "make themselves targets" by signing onto a discharge petition.

"If 218 people are hell-bent on doing something in the House, they're going to get it done," Glassman says. "You can block them, you can slow them down, but they're going to win. But nobody's hell-bent on doing this in the Republican Party."

House Democratic leaders say they are confident that there are at least 300 votes in favor of the supplemental funding package should it get to the House floor. But with some diminished support among progressives, and skepticism from Republicans, getting to 218 votes to even bring up the measure represents a major challenge.

What's in the foreign aid package?

The legislation would provide tens of billions of dollars in aid to U.S. allies, including about $60 billion for Ukraine and $14.1 billion for Israel, along with around $9.2 billion for humanitarian assistance in Gaza. Last month, a bipartisan group of senators coalesced around the package, propelling it to passage after months of disagreement about how to move forward.

The legislation notably leaves out enhanced border security measures, after congressional Republicans last week rejected a bipartisan border agreement negotiated in the Senate that former President Donald Trump opposed. But House Republican leaders have nonetheless fiercely criticized the foreign aid bill for failing to address the U.S.-Mexico border.

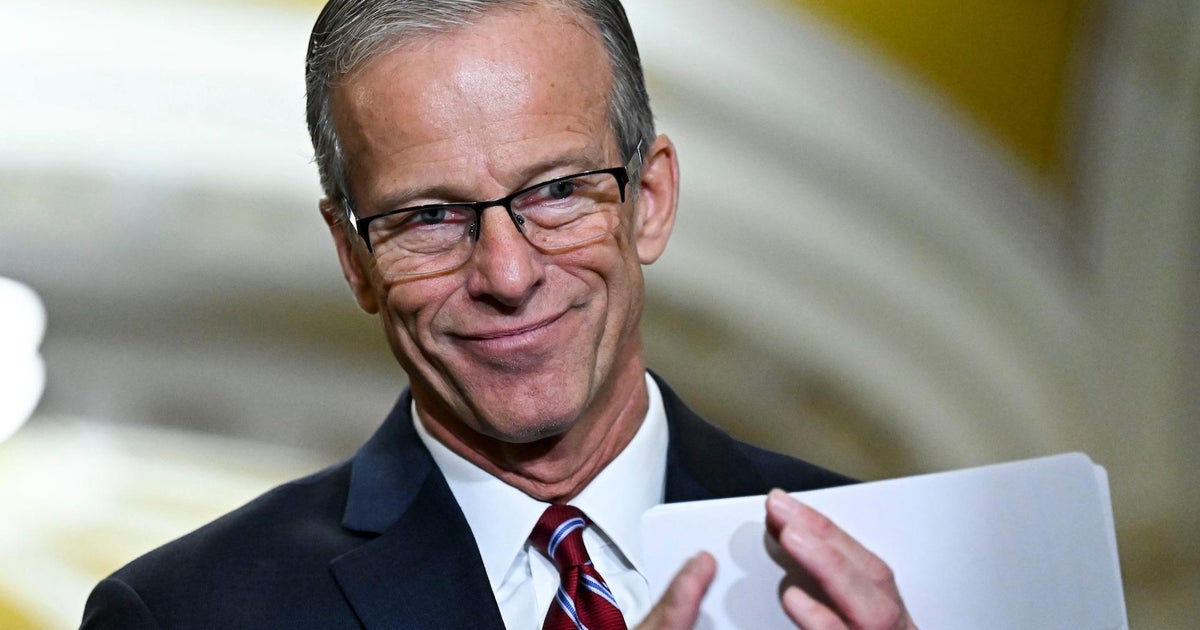

Johnson, the speaker, released a statement hours before the Senate approved the foreign aid bill casting doubt on whether the bill would get a vote in the lower chamber, saying that "in the absence of having received any single border policy change from the Senate, the House will have to continue to work its own will on these important matters."

The Louisiana Republican added during a news conference a day later that "the Republican-led House will not be jammed or forced into passing a foreign aid bill that was opposed by most Republican senators, and does nothing to secure our own border."