Did military rules cost a soldier his life?

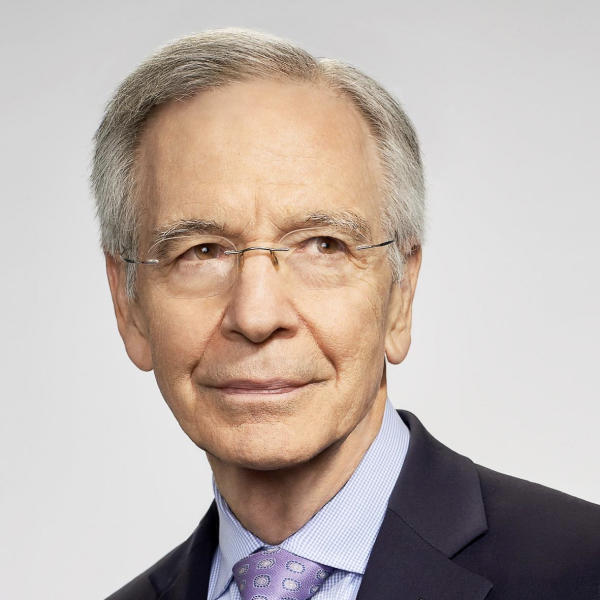

Combat medics call it the golden hour -- the window of opportunity to provide treatment and save a life. On a September night in Afghanistan, the minutes ticked away as an American soldier lay wounded, waiting to be evacuated. CBS News national security correspondent David Martin looked into the problem.

A roadside bomb just went off. A soldier let out that timeless battlefield cry: "Medic!"

Specialist Chazray Clark stepped right on the bomb and lost both feet and his left forearm. The race to get him to a hospital was videotaped by freelance journalist Michael Yon.

"One-two-three lift. Let's go guys we got to get him out of here," said a soldier on the tape.

His commanding officer, Lt. Col. Mike Katona, seemed confident Clark would survive.

"He's going to make it," he said at the time. "He's got three good tourniquets on. I have him stablized. He's doing good."

Medevac helicopters were less than five minutes flying time away. So the odds were with Clark, who seemed fully alert but in pain.

"I need something please," said Clark on the tape. "It hurts."

But the minutes ticked by. Lt. Col. Katona wanted to know what was taking so long.

Katona: "Hey, what time did you make that call?"

Soldier: "It's been over 30 minutes, sir."

Clark's medevac had been waiting for an armed escort but all the Apache gunships were off on other missions. Under the Geneva Convention, medevacs marked with red crosses cannot carry weapons. The red cross is supposed to make them off limits to enemy fire -- but doesn't. In a six-month period last year medevacs came under fire 57 times.

"We're taking fire," a medevac pilot says in footage from a previous incident. "We just got hit in the lower belly just to the northside of the aircraft. (sound of machine gunfire)"

On this night, the wait for an armed escort meant the medevac did not get to the landing zone where Clark was fighting for his life until 47 minutes after the call for help went out. It took another 12 minutes to load him aboard and fly to the nearest hospital. It was the last hour of Chazray Clark's life.

"My husband lay there wondering why nobody's coming to get him -- for how long?" asked Clark's wife Christina. "Like 40 minutes, an hour?"

"It was 59 minutes, according to the logs," said Martin.

"Fifty-nine minutes," said Christina, crying. "Why did it take them that long? There's no excuse."

Clark's wife did not object to CBS News showing her husband's dying moments because she wants an answer.

"I just don't understand why -- can't they take the red crosses off," she said, "and put machine guns on them? Why do they have to wait for somebody to escort them?"

That would be permitted under the Geneva Convention, but Lt. Gen. John Campbell says it would not save more lives.

"I don't think arming a medevac bird or taking a cross off a medevac bird will change whether or not we can get in and save our soldiers," he said.

Machine guns would add weight and reduce the number of patients a medevac could carry and would not bring nearly as much firepower as an Apache escort. Today in Afghanistan, a wounded soldier stands a 92 percent chance of surviving -- the highest rate of any war. Campbell, a former commander in Afghanistan and now chief of army operations, says that is the best argument for unarmed medevacs.

"I lost 235 soldiers in the year that I was there," said Campbell. "You don't think I would do everything I could to make sure that that didn't happen?" he said. "If I thought arming a medevac bird or taking a cross off would save additional [soldiers], I'd do it in a heartbeat."

The odds started out in Chazray Clark's favor. But by the time that medevac with its red cross found an armed escort and picked him up, he was too far gone to save.