Meet the diabolical ironclad beetle, which can survive being run over by a car

Scientists are unraveling the mystery of a bug with one of the coolest names in the animal kingdom: the diabolical ironclad beetle.

Phloeodes diabolicus has one of the toughest natural exoskeletons scientists have ever seen. According to research published Wednesday in the journal Nature, the insect's armor is so durable, few predators have successfully made a meal out of it — and it can even survive getting run over by a car.

This is a bug that scientists famously need to drill a hole into before they can stick a pin through it.

A team from Purdue University and the University of California, Irvine (UCI) have deduced that when an extreme amount of pressure is put on the beetle, its "crush-resistant" shell adapts to the situation by stretching, rather than shattering. Its nearly indestructible shell, coupled with its convincing acting skills when it comes to playing dead, leave the beetle with few predators.

"The ironclad is a terrestrial beetle, so it's not lightweight and fast but built more like a little tank," lead author David Kisailus, a UCI professor of materials science and engineering, said in a news release. "That's its adaptation: It can't fly away, so it just stays put and lets its specially designed armor take the abuse until the predator gives up."

In compression tests, researchers found the beetle can withstand a force of about 39,000 times its body weight — the equivalent of a 200-pound man enduring the weight of 7.8 million pounds.

So, how does the seemingly indestructible bug manage to survive against all odds?

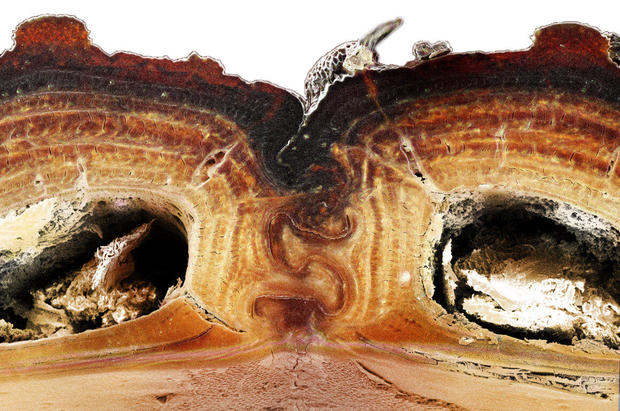

Scientists have found that the shell of the bug, which is native to desert habitats in the Southwestern U.S., has evolved to protect it. Specifically, its elytra — the blades that open and close on the wings of aerial beetles — have fused together to act as a solid shield for the beetle, which can't fly.

Analysis of the elytra revealed that it's made of layers of chitin, a fibrous material, and a protein matrix. Its exoskeleton contains about 10% more protein by weight than that of a lighter, flying beetle.

Under compression, the jigsaw puzzle-like structure of the elytra doesn't snap as expected, but rather, fractures slowly.

"When you break a puzzle piece, you expect it to separate at the neck, the thinnest part," Kisailus said. "But we don't see that sort of catastrophic split with this species of beetle. Instead, it delaminates, providing for a more graceful failure of the structure."

Scientists believe that understanding just what makes the iron beetle so tough will have practical applications for humans, too. Kisailus said that new, extra-strong materials based on the bug's characteristics will drastically improve the durability of aircraft, automobiles and more.

Kisailus and his team mimicked the structure of the bug's exoskeleton using carbon fiber-reinforced plastics. The result was both stronger and tougher than current aerospace designs.

"This study really bridges the fields of biology, physics, mechanics and materials science toward engineering applications, which you don't typically see in research," Kisailus said. "Luckily, this program, which is sponsored by the Air Force, really enables us to form these multidisciplinary teams that helped connect the dots to lead to this significant discovery."