Details on infamous O.J. Simpson glove revealed in new documentary

NEW YORK -- What more is there is to say about O.J. Simpson and the age of race relations he helped define?

Turns out there's at least 7 1/2 hours more as crafted by filmmaker Ezra Edelman in his breathtaking documentary, "O.J.: Made in America."

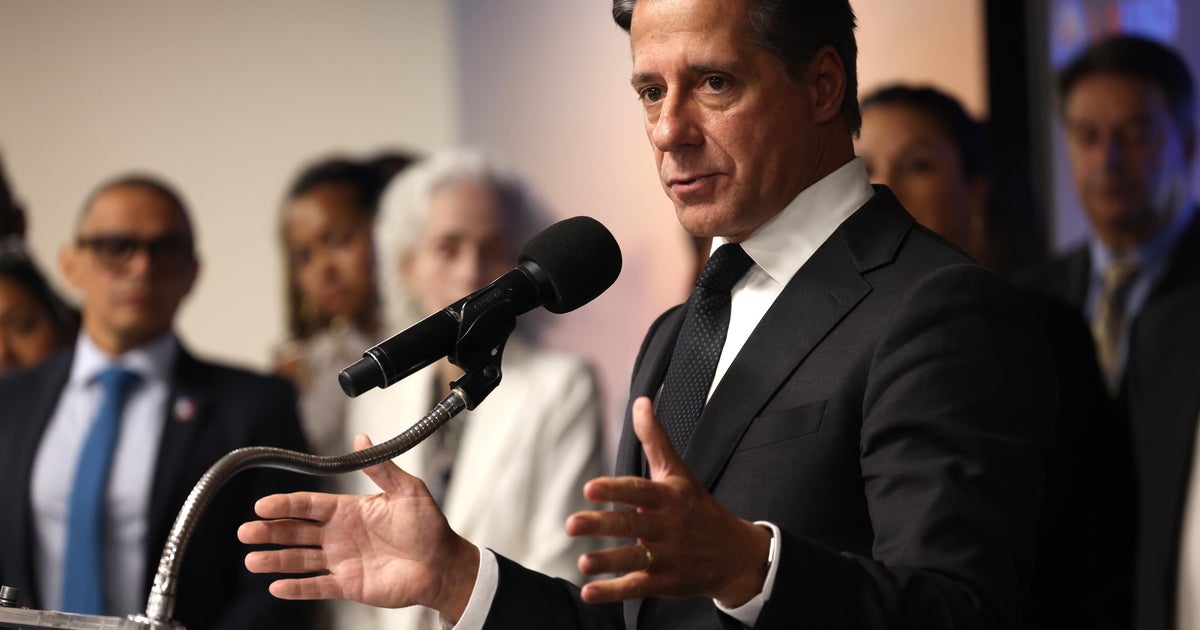

On "Good Morning America" Thursday, Gil Garcetti the Los Angeles District Attorney during the O.J. trial, reacted to the new film, and particularly, the infamous O.J. glove.

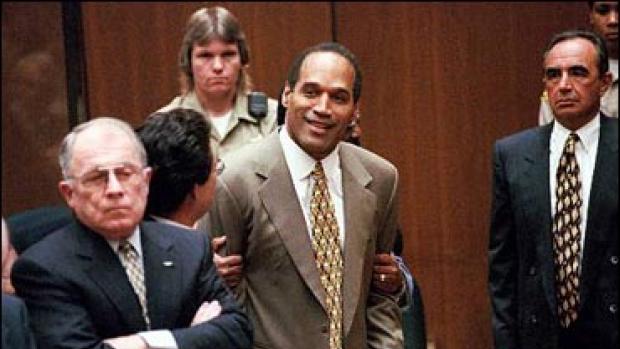

During his trial, Simpson famously tried on a bloody glove discovered at his house. That evidence was dismissed by his attorney Johnnie Cochran after the gloves were shown to be too small.

"If it doesn't fit, you must acquit!" Cochran told the jury.

"What we didn't know until I saw it on this film was that O.J. Simpson was taking arthritic medication for his hands and he was told, 'If you stop taking this arthritic medication, your hands will swell. Your joints will stiffen.' My God," Garcetti said on GMA.

Arriving two decades after Simpson was acquitted of murder charges for the death of his ex-wife Nicole and her friend Ronald Goldman, the film covers the slayings and the ensuing Trial of the Century in you-ain't-seen-nothing-yet detail.

But it goes beyond that, framing Simpson's life and career against the racial turmoil and Civil Rights struggle from which he was largely insulated by the warm embrace of the white mainstream.

His fame and public adoration flourished while, across town, black neighborhoods burned. He was raised to exalted heights as a one-of-a-kind celebrity whose transgressions (including a pattern of spousal abuse) were overlooked as incompatible with his All-American image.

Then came the murders and the trial, when Simpson, who had successfully disavowed his blackness as a canny career move, reversed course. In the film, you hear him declaring that, for the trial, "The system has forced me to look at things racially."

"Made in America" premieres its opening segment on ABC on Saturday at 9 p.m. EDT, then moves next week to ESPN, where all five parts will air on June 14, 15, 17 and 18.

It is thick with archival footage and personal video penetrating far beyond the media circus the trial became. It hears anew from 66 people, both familiar and obscure, from Simpson's life -- though not from Simpson himself. It teems with information you've forgotten by now if you ever knew it, as it draws connections you would never think to make. It's illuminating, gripping and, at times, downright astonishing.

A BROAD CANVAS

"I'm very much a product of my black mother and my white Jewish dad," says Edelman, noting that, like "Made in America," his previous films (including "Requiem for the Big East" on ESPN and "Magic & Bird: A Courtship of Rivals" on HBO) "have been about race and historically based, as much as they are about sports."

But he dismisses the facile suggestion that such a pedigree qualifies him to tackle racial issues from a neutral vantage point. His particular knack, he says: "I'm an observer."

For his current project, he was invited to observe a subject on a larger scale than he had ever had before.

"The canvas ESPN was offering meant that I didn't have to go straight to the thing that I wasn't interested in, which was the murders and the trial," he says. "I could tell a story about Los Angeles, and about race in America, and about identity.

"All O.J. had to do to get recognized is to run a football. And almost concurrent to that you have a community of people whose only way to get recognized is to burn their community down during the (1965 Watts) riots. Those were the two tracks I was trying to home in on, knowing that they will intersect 30 years later."

REACTING TO THE VERDICT

Intersect they did. But Edelman, a busy Yale student at the time, says he didn't really follow the trial.

Then, when the verdict was announced on Oct. 3, 1995, "I was hoping that this person, who I held in certain regard, was not capable of doing those things." And he understood those who greeted the verdict as belated payback for a justice system and police force long stacked against them.

But as he researched the film, Edelman was bowled over by the mountain of evidence against Simpson.

"I was pulled by emotion, but I'm an intellectually driven person," he sums up. "I see this in a bifurcated manner."

GUILTY OR NOT GUILTY?

Prior to the double murders of June 12, 1994, Simpson, who rose from the San Francisco projects, had enjoyed a brilliant athletic career. He pioneered as a black pitchman for Chevrolet, RC Cola and, of course, Hertz car rentals. He appeared in hit movies.

Then the murder trial "reduced all that had gone before to one line: football star, Hertz, 'Naked Gun.' The story suddenly became: Is this guy a murderer?

"But I knew his previous life made him a relevant figure to explore other, larger themes."

But was he guilty?

"I don't care. That relieved me as a filmmaker from any burden of, 'This is what you're supposed to think.'"

Edelman knew the larger truths he was seeking would supersede the guilt or innocence of one man - even The Juice.

SCOOPED?

Yes, Edelman felt a certain queasy feeling when he learned of FX network's drama miniseries, "The People vs. O.J. Simpson," which concluded its 10-episode run in April.

"We wondered: With all the work that we put into our project, is this going to render ours obsolete?"

But ecstatic early response to "Made in America" may well result in FX's miniseries serving as a warm-up act for Edelman's film.

"I have to acknowledge that maybe it's a good thing," he says. "I certainly underestimated the hold that O.J. and his story has over our culture in a way that I find to be fascinating and depressing and disgusting at the same time."

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

The film follows Simpson into the present day, as, at age 68, he is serving 33 years for a 2007 hotel-room heist (covered in the film in tragicomic detail).

In an audio recording from jail, he is heard to say, "I don't know how I ended up here."

By any measure, he's a fallen man whose life took a bizarre turn at age 46. And a man no one will ever forget.

"The guy had one ambition in life from the time he was a kid: He wanted to be famous," says Edelman, wondrous at the irony of how it came true. "Nothing could have made him more famous than being put on trial for murdering his ex-wife."