Two men jailed for murders they didn’t commit join forces to serve others

Two men imprisoned for murders they didn’t commit are getting a new taste of freedom. They’re now business partners in a new Brooklyn restaurant in New York. But their ambitions stretch beyond the food they serve.

The two didn’t know one another growing up in Brooklyn. Their bond was developed behind bars, where both men worked together for more than 20 years as jailhouse lawyers to exonerate the wrongfully convicted, including themselves. Now they’ve opened a restaurant, where every day is a celebration of their efforts, reports CBS News correspondent Michelle Miller.

At Brooklyn’s Brownstone, Derrick Hamilton is growing accustomed to celebrity. It’s an adoration that has little to do with running this restaurant, where the bar is often packed and spicy Jamaican dishes like Rasta Pasta are making the two month-old business a popular destination.

“What did you two know about the restaurant business?” Miller asked.

““I knew nothing,” Hamilton said.

“And I still know nothing. But we’re learning as we go along,” said his partner, Shabaka Shakur.

Hamilton and Shakur may be new to this competitive business, but both have faced steeper odds for success.

“I spent a total of 30 years in prison, 21 straight the last time,” Hamilton said.

““I did 27 and a half years straight,” Shakur said.

“He had came in for a double homicide, said he was innocent,” Hamilton recalled.

“Did you believe him?” Miller asked.

“Yes, absolutely,” Hamilton said.

“Why?” Miller asked.

“‘Cause I was convicted of a crime I didn’t commit,” Hamilton said.

While in prison, they discovered they had something else in common; both men believed they were framed by the same New York City police detective: Louis Scarcella.

“I believed him when he said the police officers had framed him,” Hamilton said.

“Because it happened to you,” Miller said.

“Yes,” Hamilton said.

But proving they were wrongfully convicted would take decades. Nearly every day behind bars, they dedicated their time to studying law.

“When did you say, ‘I’m going to the law library?’” Miller asked.

“Day one for me,” Hamilton said. “Day one. I mean, I knew that one day I would be getting out of prison, ‘cause the evidence spoke louder than me.”

“So how did you essentially free yourself?” Miller asked.

“Studying. It was refusing to accept decisions from judges that were wrong. And I just went back every time. I said, ‘Judge, you were wrong,’” Hamilton said.

“Derrick Hamilton is just a brilliant guy,” said Barry Scheck, co-founder of the Innocence Project. “He is as good a lawyer as you’ll find and certainly among jail house lawyers, you know, the best.”

Since co-founding the Innocence Project in 1992, Scheck helped exonerate 190 former inmates. He was not one of Hamilton or Shakur’s lawyers. He said it was their own grasp on the law that afforded their freedom.

“The odds are enormous and it takes people of remarkable resilience, intellect, and character to succeed and that’s who these guys are,” Scheck said.

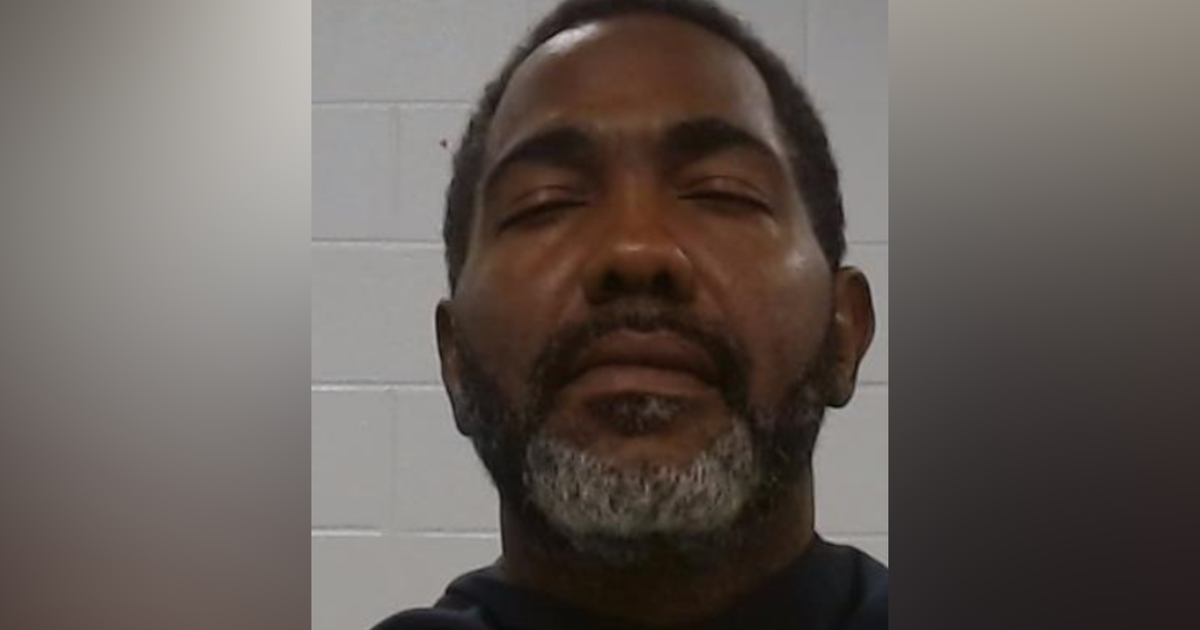

Louis Scarcella, the New York City police detective who helped imprison both men, is now retired. But allegations including “evidence manipulation” led judges to overturn 11 of his convictions and settlements have cost the city more than $30 million.

The Brownstone is where Shabaka Shakur and Derrick Hamilton chose to invest some of their settlement. But it’s not where they spend most of their time; like they once did from the prison library, Shakur and Hamilton continue to work full-time on behalf of the wrongfully convicted.

“They say two percent at the very minimum of two million people that’s in prison is innocent,” Hamilton said. “So when you look at that percentage, to me that’s too high a number to just turn your back and walk away from.”

So why go into the risky restaurant business? Because it offered an opportunity to re-connect with their old neighborhood -- one they hadn’t seen in more than 20 years.

“We knew that once we were released, that people are always going to have that stigma against you that you were in prison,” Shakur said. “So we wanted to prove that we were assets and not liabilities, that we could go back into the community and be productive citizens.”

The men also hire many employees who have trouble finding jobs because of past felonies.

“If your ego doesn’t stop you from picking up a broom and a mop and you want to work, we got you,” Shakur said. “The kids in this neighborhood, they come in here, we give them a few dollars to help us clean the windows or wash dishes to keep them off the streets.”

“See, I didn’t want to say that part. I don’t want all the kids knocking here,” Hamilton said, laughing. “But we do do that.”

“We do do that and they know because they come and hustle us every day,” Shakur said, laughing.

“So you both fought a very, very long time for this kind of an opportunity. What’s the best part of living it?” Miller asked.

“Just living free,” Shakur said. “Every day is a blessing, and now I’m here and not only am I here, but I’m able to provide a service and a place for other people to come in here and enjoy their lives.”

The two men have worked on dozens of cases apart from their own, and Hamilton said he helped free five other men, including his friend, Shabaka.

Both agree the restaurant has been a worthwhile adventure for the past two months. But fighting for the wrongfully convicted has become their calling.

Former NYPD Detective Louis Scarcella denies any wrongdoing in his conviction cases that have since been overturned.