More parents deported without their kids may be able to return to the U.S. — if advocates can find them

Los Angeles — Cleivi's youngest daughter, Alison, would not let go of her or the blue welcome poster she made for her father, Fernando Arredondo. Her eldest girls, Keyli and Andrea, scoured the arrivals area for the best vantage point to catch the first glimpse of their father. Cleivi herself was visibly nervous.

Shortly before midnight, Fernando's group of migrant parents, lawyers and faith leaders emerged. Andrea, 14, was the first to see him, but it was 7-year-old Alison who rushed towards Fernando, yelling, "Daddy!" One by one, Fernando hugged his daughters before kissing a teary Cleivi and lifting Alison in the air.

"Thank you, God. Thank you, God," Fernando said in Spanish, raising his hands and looking upward as he embraced his family for the first time in nearly two years.

The Guatemalan family's three-year quest to live together in the safety of the U.S. finally seemed to be within reach with Fernando's arrival at Los Angeles International Airport on January 22, made possible by a court mandate and advocacy groups like Al Otro Lado. While overjoyed to be back with his family, his thoughts immediately went to the other Central American families who had suffered the same plight.

"We all deserve an opportunity in life," he told CBS News. "And to all the parents who are watching us, who are separated from their children, have patience, have faith and pray a lot because miracles exist."

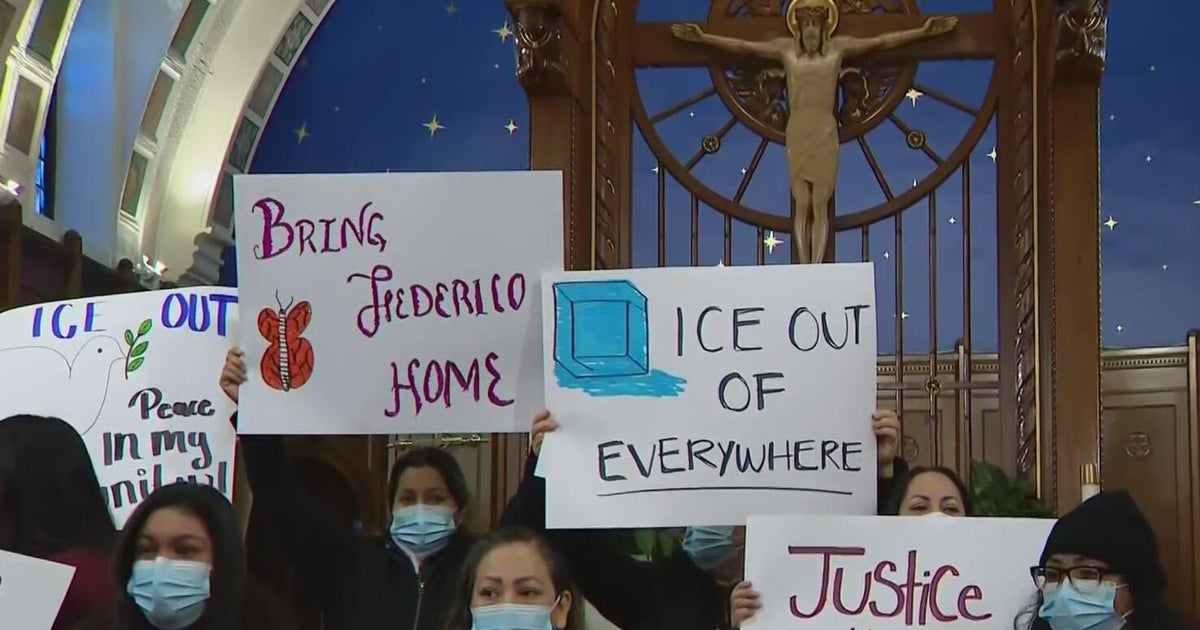

The American Civil Liberties Union, or ACLU, believes a precedent has been established following the court decision that allowed Fernando and eight other migrant parents to make a historic return to the U.S. last month.

In his ruling last September, Judge Dana Sabraw of the U.S. District Court in San Diego said Fernando and 10 other parents could come back to the U.S. to reunite with their children and pursue their asylum cases because he found they had been unlawfully deported after being provided false information by U.S. officials or coerced into waiving their rights.

If it can prove the parents were unlawfully deported, the ACLU believes Sabraw could order the return of some of the hundreds of parents the group estimates were expelled to Mexico and Central America after being separated from their children by U.S. officials.

"If we find out they were misled or coerced into giving up their asylum rights, we will ask the judge to have them be brought back as well," Lee Gelernt, the ACLU's top immigration litigator, told CBS News. "I think these nine are a test case for what may happen going forward."

"Unreachable" parents

In the summer of 2018, the ACLU formed a "steering committee" to locate and interview parents the Trump administration had deported after splitting them up from their kids. Since then, the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison and the non-profit organizations Justice in Motion and Kids in Need of Defense have undertaken what Sabraw has called "Herculean efforts" to locate these families.

Through phone calls and on-the-ground searches, the committee located Fernando and nearly 500 other parents who were deported after being separated from their children in the spring of 2018 under Trump administration' systematic practice of separating families. Most either chose to have their children sent to them in Central America or waived their right to reunification to allow their kids to continue their asylum cases in the U.S.

In October 2019, the U.S. government revealed it had separated an additional 1,556 children from their parents between the summer of 2017 and the height of the "zero tolerance" policy in June 2018. Since Sabraw said these families could potentially be eligible for reunification, the steering committee has spent months tracking them down.

The committee has reached 346 parents or their attorneys. But it has been unable to reach the rest — nearly 700 — since the phone numbers provided by the administration are often stale or outdated.

The committee continues to call 386 of these parents, but it has deemed the rest "unreachable." Justice in Motion has led the campaign to find them, dispatching 22 team members to conduct on-the-ground searches in cities and remote villages across Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

The group has tracked down at least 113 parents, and continues to scour the region for the rest, sending 1,100 letters to addresses provided by the government and establishing hotlines for separated parents. When U.S. immigration files don't include a home address, advocates have turned to local public records.

"Defenders are using all manner of transport. Some use motorcycles, motorbikes and scooters. Some need to rent four-wheel drive vehicles, and others are going on foot or bike," Nan Schivone, Justice in Motion's legal director, told CBS News. "There's a lot of effort to actually reach the community of origin, whether it is listed by the government or listed on public record documents."

Out of the families it has reached and interviewed in their home countries, Justice in Motion said it has identified parents who are still without their children and could be eligible for the same relief Fernando and 10 other parents were granted last September. The non-profit has been referring such cases to the ACLU for future litigation.

"We're finding similar situations, for sure: Families who are still in need of protection, who suffered a due process violation at the moment of separation and in the process of seeking asylum in the U.S.," Schivone said.

Fernando said he wants the same opportunity for other parents because he's sure some families have endured ordeals similar to the one experienced by his family before last month's reunification.

"Mommy, they're going to kill us"

After hearing more than a dozen loud, piercing bangs that sounded like explosions, Cleivi immediately worried about her children.

"When I went outside, my son was lying on the ground," Cleivi told CBS News in Spanish, breaking down into tears while recounting a tragic episode from April 2017 that has become etched in her memory.

Her 17-year-old son, Marco, was gunned down outside his grandmother's home in a working-class neighborhood in the outskirts of Guatemala City. Standing next to Marco as his body was pierced by bullets was his sister, Keyli, who was getting ready to celebrate her quinceañera, a traditional Latin American rite of passage for girls commemorating their 15th birthday.

"Keyli was next to him. They were together," Cleivi said. "And Keyli witnessed that."

Cleivi's husband Fernando, then a taxi driver, raced to see his family. "The scene was horrific when I got to my mother-in-law's house," Fernando later wrote in a court filing. "Everyone was still screaming, and I saw Cleivi holding Marco in her lap. Marco was already dead."

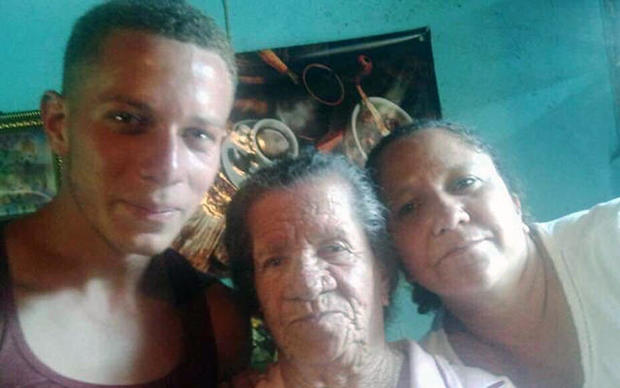

Two young men had shot Marco multiple times in his head and abdomen, according to a report by Guatemalan police. A photo shows Cleivi on the ground, clinging to her son's body with onlookers and police surrounding her.

"That day changed my life," Cleivi said. "Drastically."

The family is certain Marco was killed because he and his father were part of a neighborhood watch created to protect their community from gangs.

The day after Marco's burial, Fernando said two armed men warned him that they would kill the rest of his family if he continued talking to the police. "They knew all our names, where we lived, and how to find us," he wrote in a court declaration.

The family said Guatemalan authorities were unable or unwilling to fully probe Marco's murder and could not ensure they would not be harmed. They left their home of 12 years and moved from place to place, but never felt safe.

Cleivi said she realized they had to leave Guatemala when a neighbor was having a birthday celebration. "They started to set off fireworks. This girl was traumatized," she said, referring to Alison. "She yelled, 'Mommy, they are going to kill us. Mommy, let's get out of here.'"

In February 2018, the family set out for the U.S. through Mexico. But two hours away from reaching the U.S. southern border, Mexican officials escorted Fernando and Andrea off the bus they were traveling in.

Cleivi said she had promised Fernando she would push forward in the event they were separated. So she continued the journey with Keyli and Alison, telling U.S. officials at a Texas border crossing in May 2018 they feared returning to Guatemala.

The family was detained together in a hielera, or icebox, what many migrants call Border Patrol holding cells where they are issued Mylar blankets and sleep on concrete floors. The conditions were particularly difficult for 5-year-old Alison. "I grabbed a roll of toilet paper and wrapped her from head to toe, like a mummy," Cleivi said, remembering one sleepless night inside the cell.

Cleivi, Keyli and Alison spent three days in Border Patrol custody before being released to a local shelter. Fernando and Andrea had reached the same U.S. border crossing less than a week after the rest of the family. But the two met a different fate.

"We all pounded on the cell door"

The father and daughter were separated during the administration's "zero tolerance" border crackdown. "They separated us out of nowhere," Andrea told CBS News, adding later, "They took me to a place with other children. The younger kids were crying and that scared me even more."

Border officials separated more than 2,800 migrant families before a court ruling in June 2018 brought an end to the practice. Some families, like Fernando's, were separated even after asking for asylum at an official border crossing.

Fernando said his pleas to find out why he had been separated from Andrea went unanswered. "Around 3:00 am on the day that Andrea was taken from me, all the children who were in detention were lined up outside," he wrote in a court filing. "We could see them through the window of our cell. We all pounded on the cell door, to ask what was happening. None of the officials responded to our questions."

Andrea spent about two weeks in a government shelter in San Antonio before reuniting with her mother and sister in Los Angeles. Fernando, however, remained detained for three months and was shipped between four different detention centers in Texas and Georgia.

In Georgia, according to court filings, Fernando suffered symptoms of dengue fever and from a urinary tract infection. He lost eight pounds. Growing increasingly desperate, Fernando tried to find solace reading the Bible. "I prayed a lot to avoid thinking about suicide," he wrote.

After weeks in detention, Fernando was told he had failed his "credible fear" interview, the first step migrants need to pass to request asylum. "I was feeling desperately sick, psychologically and physically, and the ICE official made it very clear that there was nothing I could do to get asylum in the U.S.," Fernando wrote in a legal declaration. "I did not know how long they were going to keep me in that dreadful place."

Fearing prolonged detention, Fernando signed a document reviewed by CBS News in which he declined to request that an immigration judge review the credible fear assessment. He was deported to Guatemala in August 2018 and immediately went into hiding.

Fernando's deportation occurred roughly a month after Sabraw, the judge overseeing the main family separation case, ordered officials to reunite families and to halt the deportation of separated parents. "Fernando was deported in violation of Judge Sabraw's own order," Linda Dakin-Grimm, the family's attorney, told CBS News.

"We're safe here"

While Fernando hid from the gang members who killed his son, Cleivi and her daughters found some stability. She rented a home in the predominantly Latino Florence neighborhood of Los Angeles, where the girls enrolled in local public schools.

Still, Cleivi never stopped worrying about Fernando's safety: "A part was missing to complete our happiness." With his return last month, Cleivi said the family's "puzzle" is now complete.

The family's lawyer has merged their different asylum cases into one, and their next hearing in immigration court is scheduled for July. Though there is still some uncertainty regarding the fate of their asylum petition, 7-year-old Alison is happy her family is finally living together on American soil.

"We're safe here," she said.