Deep Springs College brings rigorous academics to a ranch in the high California desert

Ahh college... Lazy afternoons on the quad, parties, homecoming games and, too often, crippling student debt. Tonight, we'll take you to a school that has none of those. In terms of class size, it's one of the smallest colleges in the country. In terms of landmass, one of the largest. For two years, around 26 of the world's brightest come to California to live in seclusion, govern their own affairs and submit to rigorous coursework and hard labor on a working ranch. As we first reported last fall, it's an experiment in education designed to forge the leaders of tomorrow, dreamt up by an eccentric industrialist a century ago. Think your school was rigorous? Think your school had its quirks? Join us on a visit to Deep Springs.

In the shadow of eastern California's High Sierra, hemmed by twisting mountain passes, Deep Springs College is an oasis of green set amid a no man's land of sage-brush and endless sky.

Here, students from around the world labor in the classroom and on the grounds, where there is no football field, but there is an alfalfa field. And the syllabus includes philosophy, calculus and pre-dawn cow milking. Student-farmers grow the produce that student-cooks prepare.

There are student mail carriers, student mechanics...

And student ranchers who drive some 300 head of cattle across a valley almost twice the size of manhattan.

Jon Wertheim: had you ever ridden a horse before you came here?

Ziani Paiz: Ah like a pony ride once or twice. [laugh]

When we visited, Ziani Paiz was one of two students assigned to work as a Deep Springs cowboy.

Jon Wertheim: You could have gone to a school with-- with concerts and parties, and football games. Do you ever feel like you're missing out?

Ziani Paiz: No. [laugh] Not at all. I feel like never again in my life am I gonna have an opportunity to live in a place like this.

Like everybody here, Ziani was an academic all-star in high school. People back home in east LA. Found her choice of college mystifying.

Jon Wertheim: What'd your friends say when you told them where you were going to school?

Ziani Paiz: Oh, they thought I was so stupid.

Jon Wertheim: What do they think you should have done?

Ziani Paiz: Taken a four-year scholarship to a real school.

Jon Wertheim: Was that-- was that an option?

Ziani Paiz: Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: C-- can I ask what school?

Ziani Paiz: Berkeley. [laugh]

Jon Wertheim: you had a four-year scholarship lined up to Berkeley.

Ziani Paiz: Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: You said, "Nah. I'm-- I'm gonna come to the desert and-- be--be a cowhand"

Ziani Paiz: Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: What-- what is this feeding in you? What-- what are you getting out of this?

Ziani Paiz: At base level, you know, fun. It's a lot of fun to, like, run on a horse and chase a cow, you know. But I think you-- you also do genuinely learn life skills from that. I think you-- you can't quit when the work gets hard you know.

Deep Springs was built on a kind of formula: take a handful of the best and brightest, put them in the middle of nowhere. Add rigorous academics, labor, and autonomy and you'll get future leaders.

It's not for everyone. A particular type of person finds all this appealing. Content practicing Brahms and bailing hay. Casual, brainy, indifferent to sleep.

Jon Wertheim: What else typifies a Deep Springs student?

Ziani Paiz: We're typically pretty awkward. In the real world, we're definitely not the cool kids. What else? We're not delicate, usually. We're not usually some delicate people.

They can't be. Students are required to perform at least 20 hours of labor a week on top of a full college course load.

Alice Owen took us through her routine maintaining irrigation lines. As we quickly learned, summer camp, this ain't.

Jon Wertheim: This is significant hard, potentially dangerous labor. When people make mistakes, inevitably, what is the consequence of that?

Alice Owen: If I can't grow a field of alfalfa, then the cows will not have anything to eat. If you can't get dinner ready on time you have to apologize to people, and sometimes the mistakes are really hard to fix, or they're unfixable and then you just have to take the weight of, "well I, I messed up really big."

Jon Wertheim: It seems sometimes today that colleges do everything they can to shield kids from discomfort, from hardship. That doesn't seem to be the philosophy here.

Padraic MacLeish: No, it-- it absolutely isn't.

That's Padraic MacLeish - a student here 20 years ago who was so entranced by the place, he came back to work as director of operations.

Padraic MacLeish: If you want to finish the job before dinner you need to put some hustle in and work a little bit harder.

Jon Wertheim: But why? What's the reasoning behind that?

Padraic MacLeish: What we are doing is trying to prepare them to live lives of service.

Padraic MacLeish: When they see a problem, when they see something that needs to be done, you shouldn't go looking over your shoulder for somebody else to do that.

Jon Wertheim: There's a self-reliance you get here.

Padraic MacLeish: Exactly. I hope so anyway.

Padraic is part of a motley crew of more than a dozen faculty and staff. The salary is modest compared to other schools, but food and housing are included and many live here with their families. Some come armed with Ph.D.s.

Others with high school diplomas. Tim Gipson showed up here with his guitar six years ago, after running cattle from Montana to Texas.

Jon Wertheim: These are some of the smartest kids in the country. Can you tell that when you're out here on the ranch?

Tim Gipson: Sometimes no [laugh].

As ranch manager, he fills a variety of roles. Among them, cowboy coach.

Jon Wertheim: These kids could go to college almost anywhere in the country. Why would you do this?

Tim Gipson: One thing they have in common, almost all of the students that come here, is that they're searching for something different and unique. And they're really searching for a deeper meaning of life.

It's a two-year school, after which, students usually transfer to finish their degrees at the most selective universities. Alumni include diplomats, Pulitzer Prize winners and famed physicists.

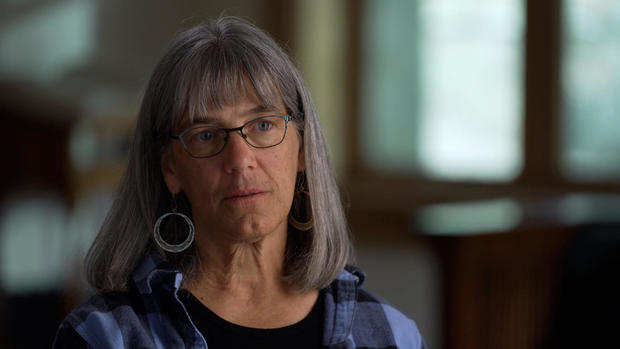

Sarah Stickney: One of the classic things that happens to students when they come here is, they've been the best wherever they were. And suddenly, they're with 15 other people who have also been the best. And I think that's a hard moment for students.

When we met her, Sarah Stickney was Deep Springs' dean.

Jon Wertheim: I can't imagine they're easy to teach?

Sarah Stickney: Oh my gosh, they're magnificent to teach! They're much better than easy you know um, they have high standards. And they want a lot of attention, but not in a needy way, more like their own voraciousness and interest.

Like everyone else, Stickney wasn't just teaching these students, she was part of their lives and lived just steps away, not that there are many options out here.

It's hard to exaggerate the remoteness of this place, but here's one indication: For years, the nearest drop point for students arriving by bus was about 50 miles away, on the other side of the Nevada state line, in front of a brothel. This extreme isolation formed one of the core principles for the school's founder LL Nunn, an eccentric electricity and mining baron who believed the desert held spiritual qualities and lacked the distractions and seductions of the real world. He bought an old ranch down in this valley and in 1917 christened Deep Springs College.

Nunn, whose presence here is still ubiquitous, put up money for the school but specified the student body should be all male. It took a century, but four years ago, Deep Springs finally went coed and today, men women, everyone gets access to the free education at Deep Springs -- that's right, all the students here get a full ride.

Among her many duties, President Sue Darlington raises money from alumni needed to keep this experiment going.

Jon Wertheim: Does this place work if you charge tuition?

Sue Darlington: No.

Jon Wertheim: Why not?

Sue Darlington: The students are not consumers. Therefore they're not turning around and saying, "I have the right to this because I've paid for this." Everybody is getting the same deal. And that levels a certain kind of playing field.

The tradeoff: while other schools offer five-star amenities, here the trappings are, well, spare.

Jon Wertheim: A lot of colleges and universities, they pride themselves on their facilities and the high tech and gym. You're laughing before I even finish the question.

Sue Darlington: Yep.

Jon Wertheim: That description does not apply here.

Sue Darlington: Does not apply here. [laugh]

Jon Wertheim: Describe the decor.

Sue Darlington: [laugh] It's worn by the sand, the wind, the people. So we prioritize that everything works. And that the students also take some of the responsibility for the upkeep.

And they take responsibility for running the school.

Some rules are firm: students at Deep Springs can't drink or, except in rare circumstances, leave this valley during the semester. But just about everything else comes up for exhaustive debate, then a vote, in weekly student meetings that can make the U.S. Senate look efficient.

Alice Owen: We spend our Friday nights having student body meetings.

Alice Owen: We really do govern ourselves And-- and that can be-- tense, but ultimately it-- it can be a really exciting space, because the conversations that go on there are ones that have really high stakes for us.

Students vote on matters essential and not. Dormitory decor and whether to allow 60 Minutes on campus.

Also, which courses are offered and what professors they want to hire.

And they sift through the 200 to 300 applications every year to pick the dozen-or-so students they'll accept for the incoming class.

Jon Wertheim: Handing over power and authority to 18 and 19-year-old kids, it could lead to-- to "Animal House?" It could lead to "Lord of the Flies." But that doesn't seem to have happened here?

Sarah Stickney: Yeah. Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: Why?

Sarah Stickney: Why do we imagine that giving people who are becoming adults authority and power in their own lives, why do we imagine that's a bad thing?

Jon Wertheim: The knee-jerk answer would be "life experience." And their-- and their response here might be, "Life experience?"

Sarah Stickney: Right.

Jon Wertheim: "I-- I'm out here with an irrigation contraption."

Sarah Stickney: Exactly.

Jon Wertheim: "What's your life experience?"

Sarah Stickney: Exactly.

But from time to time, the adults have to step in. When COVID first hit the U.S., some students wanted the school to continue as usual in spite of California's lockdown. Administrators intervened, Padraic MacLeish among them.

Jon Wertheim: Difficult conversation?

Padraic MacLeish: It wasn't an easy one, but it was an important one. You know, defining the limits of self-governance are part of talking about what self-governance actually means at Deep Springs.

And speaking of experiences not offered at State-U, Ziani Paiz was preparing for an adventure: driving cattle on horseback up a remote mountain top for summer grazing.

Ziani Paiz: We're gonna chase them up. We'll keep them where they need to be. We'll work long hours. We'll read sometimes.

It fell to Tim Gipson to get her ready for that journey.

Jon Wertheim: We talked to Ziani She'd never been on a horse, barely, before she-- she got here.

Tim Gipson: [laugh] She's from East LA…

Jon Wertheim: How'd you swing that one?

Tim Gipson: Now, she had a lot of try, a lot of determination. She has a lot of desire. And that's what it takes.

Jon Wertheim: When these kids go off to Harvard and Yale.

Tim Gipson: Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: What can they bring with them they learned on the ranch?

Tim Gipson: Work ethic. Diligence. Responsibility.

Skills that will transfer when the students transfer as well, taught as they are by Socrates, Shakespeare and singing cowboys.

Produced by David M. Levine. Associate producer, Mabel Kabani. Broadcast associate, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Sean Kelly.