Debt "impasse" is actually sign of progress

This post originally appeared on Slate.

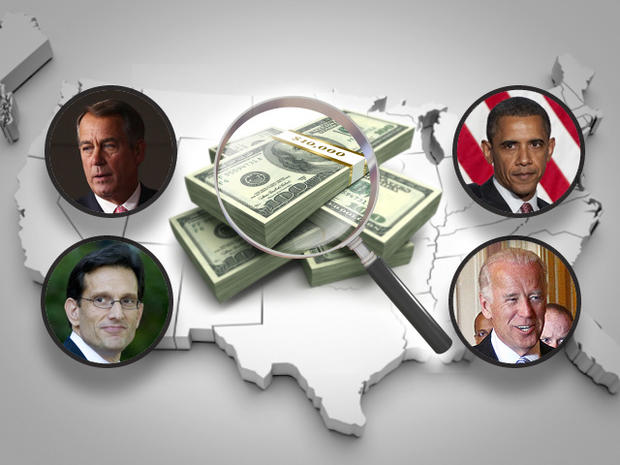

In a sign of progress, Republican appointees to Vice President Joe Biden's debt limit talks announced late Wednesday that they were pulling out of negotiations. House Majority Leader Eric Cantor and Senate Minority Whip Jon Kyl denounced the president and Democrats for wanting to raise taxes. Added House Speaker John Boehner: "The president is going to have to engage."

It sure doesn't sound like progress. But if you view these negotiations using the Saturday serial movie construct, (and all right-thinking Americans should), this is simply the drama necessary to advance the story. When the heroine is tied to the tracks and the train is approaching, the audience's blood starts to race. But in the back of our minds, we know that she's not in real danger. Whether the brakeman steps in or Shazam swoops down to snatch her, we know the situation will resolve itself.

Deficit talks implode as GOP negotiators drop out

Given the state of politics in Washington today, and the stakes in this debate, the breakdown in talks was a foregone conclusion. "We are at the impasse stage," said one administration official. It was always expected that Biden and congressional leaders would work as hard as they could, then cede the final round to President Obama and Boehner. That's where we are now, just as we were in the fight over the Bush tax cuts at the end of last year, and just as we were in the negotiations last spring over the continuing resolution to keep funding the government for this year. The leaders of the two key factions (along with their sidekicks, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell) will now have to work with the wonks doing the math and figure out which final set of compromises will be palatable to their party.

Before the final stage of backroom negotiations, there are always the denunciations, charges of unseriousness, and accusations of ideological rigidity. Why do we always come to this stage? It's a negotiating tactic, an educational exercise, and stage management. Anyone putting together a deal knows the value of seeming inflexible. Maybe you'll win concessions from the other side. Republican leaders must make a show of how difficult they are to impress their members and constituents. If a deal happened with Biden in a room and there wasn't any public outcry, conservatives would have every right to be suspicious that Republicans got rolled.

Democrats need the blow up for similar reasons. The moment allows them to try to paint Republicans as captive of their unpopular Tea Party wing, which might lower the expected level of spending cuts, or at least rearrange them if Republicans feel the heat. Both sides also need the debate to play out in public so that everyone can fully understand why an ultimate deal was the best one leaders could get.

Bob Schieffer: Dysfunctional D.C. back to square one

Throughout this drama there have always been two games to watch--public and private. While members of both parties were being tough on each other in public, golfing buddies Boehner and Obama held an unscheduled and hush-hush meeting at the White House Wednesday night.

At the same time, just because we know the ending doesn't mean there can't be a few plot twists.

The big question is what to do about taxes. According to administration officials, the deal being worked out in the room already includes some tax increases. In that case, we're about to engage in a debate about the definition of a tax increase. Closing a tax loophole increases taxes on someone, but by using a different term--eliminating "tax expenditures"--it doesn't sound as bad.

Republicans didn't have to give in on much during the negotiations over extending the Bush tax cuts and keeping the government running. But there's a bigger chance they will have to give in on something this time. To achieve the $2 trillion in spending reductions both sides have been aiming for--while at the same time protecting defense spending, a GOP priority--without raising some kind of taxes would require huge cuts in the rest of the budget. That might just be too hard to defend. "You can't make the math work without them," says one administration official, explaining why some new tax revenue will be required.

And there is another important way this story is different from the previous two: The deadline is vague. Before, everyone knew when economic doom would supposedly kick in. The tax cuts would expire on Dec. 31, and the government would not be able to pay its bills starting on April 9. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner earlier cited Aug. 2 as the end-date in this drama, but the economic pain could kick in earlier. All involved agree that the market could get spooked about the failure of a deal before Aug. 2. (Some might even say that the market is already spooked.)

A deal is still likely because two key political forces are still in play: Republicans can't risk getting blamed for causing a default on the debt, and the president can't risk getting blamed (or rather, getting any more blame) for the weak economy. Presenting himself as the adult who put together a deal between two political extremes is perhaps the best single thing Obama can do to show that he is doing something to manage the economic mess.

For the moment both Biden and Cantor say the talks are in "abeyance" (apparently SAT preparation is in full swing, though). They could resume, say Republicans, if Democrats stop trying to increase revenue by raising taxes. This takes us back to the debate over what constitutes a tax increase. It may be basic math that's driving the negotiations over the debt limit. But selling an agreement will require some fancy vocabulary, too.

More from Slate:

Supreme Court Year in Review: Sometimes the end-of-term drama obscures the truth.

Whitey Bulger arrested: How does the FBI set rewards for fugitives?

Obama's Afghanistan withdrawal: The case for making the world unsafe