Debate over $6B Los Alamos nuke lab

SANTA FE, N.M. - At Los Alamos National Laboratory, scientists and engineers refer to their planned new $6 billion nuclear lab by its clunky acronym, CMRR, short for Chemistry Metallurgy Research Replacement Facility. But as a work in progress for three decades and with hundreds of millions of dollars already spent, nomenclature is among the minor issues.

Questions continue to swirl about exactly what kind of nuclear and plutonium research will be done there, whether the lab is really necessary, and — perhaps most important — will it be safe, or could it become New Mexico's equivalent of Japan's Fukushima?

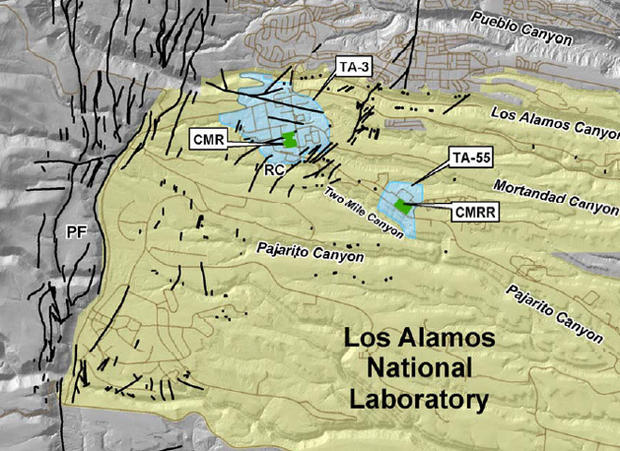

As federal officials prepare the final design plans for the controversial and very expensive lab, increased scrutiny is being placed on what in recent years has been discovered to be a greater potential for a major earthquake along the fault lines that have carved out the stunning gorges, canyons and valleys that surround the premier U.S. nuclear weapons facility in northern New Mexico.

Final preparations for the lab — whose high-end price tag estimate of $5.8 billion is almost $1 billion more than New Mexico's annual state budget and more than double the lab's annual budget — also comes as a cash-strapped Congress looks to trim defense spending and cut cleanup budgets at contaminated facilities like Los Alamos. It also comes as the inspector general recommends that the federal government consider consolidating its far-flung network of research labs.

Despite the uncertainty, the National Nuclear Safety Administration, an arm of the Department of Energy that oversees the nation's nuclear labs, is moving forward on final designs for the lab. Project director Herman Le-Doux says it has been redesigned with input from the nation's leading seismic experts, and the NNSA has "gone to great extremes" to ensure the planned building could withstand an earthquake of up to 7.3 magnitude.

Most seismic experts agree that would be a worst-case scenario for the area. But many people who live near the lab — and have seen it twice threatened by massive wildfires in 10 years — see no reason for taking the chance.

"The Department of Energy has learned nothing from the Fukushima disaster," said David McCoy, director of the environmental and nuclear watchdog group Citizens Action New Mexico, at a recent oversight hearing. That's become a common refrain since last year's earthquake and tsunami in Japan caused a meltdown at one of its nuclear plants. "The major lesson of Fukushima is ignored by NNSA: Don't build dangerous facilities in unsafe natural settings."

Lab officials say CMRR is needed to replace a 1940s era facility that is beyond renovation yet crucial to supporting its mission as the primary center for maintaining and developing the country's stockpile of nuclear weapons. While much of the work is classified, they insist the lab's mission is to do analytical work to support the nearby Plutonium Facility, or PF-4, which is the only building in the country equipped for making the pits that power nuclear weapons.

Watchdog groups, however, call it an effort by the DOE and NNSA to escalate the production of new nuclear weapons and turn what has largely been a research facility into a bomb factory.

And they are not giving up their efforts to halt the project. The Los Alamos Study Group, headed by Greg Mello, one of a number of area activists who have made a career out of monitoring LANL, has two lawsuits challenging the project and what he says is the federal government's refusal to look at alternatives despite the increased seismic threats uncovered in 2007 that have sent the price tag soaring.

Mello spends his days poring over every available public document on Los Alamos and the nation's nuclear program. And he makes frequent trips to Washington to lobby against funding for CMRR, which he says is an unnecessary attempt to "open the door for an overall expansion in intensity and scale" of the nation's nuclear weapons program.

At just about every public hearing related to the labs, Mello lines up with a regular group of aging hippies, retired scientists, former lab employees, residents of nearby pueblos as well as housewives and grandmothers from Santa Fe and other neighboring communities to oppose CMRR and anything and everything related to an expansion or continuation of the nuclear mission at Los Alamos.

While much of the public outcry over Los Alamos in recent years has focused on lagging cleanup efforts of radioactive waste and hazardous runoff into the canyons that drain into the Rio Grande, earthquake danger and the potential for catastrophic releases of radiation from existing facilities was front and center at a recent meeting in Santa Fe of the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, appointed by Congress to oversee the nation's nuclear facilities.

"The board believes that no safety issue problem in (the nation's nuclear complex) is more pressing than the plutonium facility's vulnerability to a large earthquake," the board's chairman, Peter Winokur said in reference to efforts to reinforce PF-4.

The board has worked closely with NNSA to ensure CMRR is designed to withstand a major quake, so Winokur said the board is not concerned about that project — "as long as they follow through."

It's that follow through that has watchdogs concerned.

"Los Alamos doesn't have that safety ethos needed for a facility that will store the bulk of the nation's stockpile of plutonium," Mello said

Winokur agreed that safety remains a concern at the lab.

Since the last contractor took over operations in 2006, he said, "It's fair to say they have improved safety at the sites." But he pointed to two recent memos about deficiencies in nuclear safety programs that he said underscore the fact "that the operations out there are very challenging and that there is plenty of room for improvement."

Asked if he thought it was wise to spend billions of dollars to keep the nation's nuclear weapons operations centered on an earthquake-prone mesa, Winokur said his mandate from Congress is to oversee safety, not second guess major policy decisions.

"I'll leave that to Congress and DOE about whether or not they want to build a facility of that nature in that region of the country where they do have a fairly large earthquake threat," Winokur said.