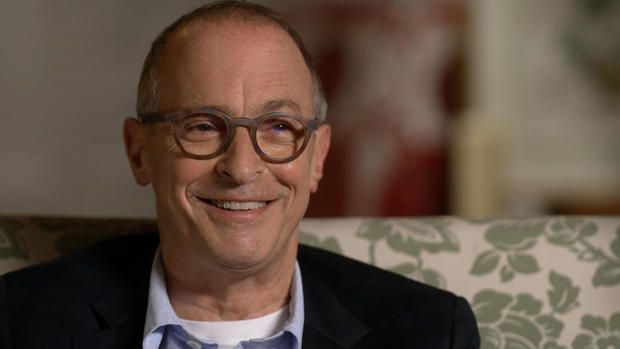

David Sedaris on finding a story anywhere and everywhere

The best stories happen to those who can tell them. It's a fundamental rule of writing - maybe of life. And for decades now, David Sedaris has taken his offbeat experiences and unfiltered observations and turned them into rollicking essays - which he not only writes masterfully, but then performs as he threads the globe on tour. It's made him among the world's bestselling authors. It's made him rich enough to buy a Picasso. It's made him a humorist on the order of Mark Twain - if Mark Twain had been discovered after writing about his job as a department store Christmas elf.

David Sedaris: I'm in show business. And I-- I love the show business life. (LAUGH) I really do. It's the laziest form of show business there is. But yeah, I think of it as showbusiness, I do.

Writers tend to be a solitary, introverted tribe. Showbusiness, the readings, appearances, book signings, often mark the worst part of the job. Not so for David Sedaris.

He turns his tours into performances, drawing big crowds to hear him hold forth on topics petty and profound. And reliably funny.

David Sedaris at one of his readings: That's what makes me unworthy of a biography, not just that I'm dull and have never been unfaithful, but that I'll zone out and think about Dumbledore, or a TV show I like called "1000-Pound Sisters."

And it's not just in front of the urban hipster crowd…

When we first met up with Sedaris, he happened to be headed to Skagway, Alaska, population 1,100, for a show at the local Eagle lodge.

Followed by a line to experience that Sedarian satire one-on-one.

He loves the interactions, stays for hours, but Sedaris also gets something practical out of this: potential material.

David Sedaris: One time I said to this woman, "when was the last time you touched a monkey?" And she said, "Can you smell it on me?" And she worked for a center in Boston that trains monkeys to act as helpers for paralyzed people.

Jon Wertheim: You had no inkling this w--

David Sedaris: I had no idea. None whatsoever. And then she invited me to the center. And so I went to the center and I had monkeys all over me.

Sedaris's ability to find a story anywhere and everywhere has helped make him a runaway success, with more than a dozen books and counting, nearly every one a bestseller, 15 million copies sold.

Jon Wertheim: Why do you think so many people relate to your work?

David Sedaris: Every night, I am on stage, and I look out, and I see people, and I wanna say, "Why are you here?"

Jon Wertheim: "Why are you here"?

David Sedaris: Yeah Because I'm thinking like, "Surely, you had stuff to do at home" the thing is I'm nobody, you know what I mean? Maybe what happens in the theater is just a celebration of our shared ordinariness.

David Sedaris at a reading: All writers are thieves, poaching a bit of one person's life, and stitching it to part of another's…

His subject matter traces the human experience, visits to the doctor, struggles in the TSA line and of course the comedy and complexities of family.

David Sedaris at a reading: "Well, I'm 100 years old," my father tells us. "Can you beat that?" "98," Amy corrects him.

Including his sister, Amy Sedaris…

Amy Sedaris: Tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick tick. (LAUGH)

Amy Sedaris: That's our 60 Minutes -- whenever we would say something serious, we went, (TAPPING) "Tick, tick, tick, tick, tick, tick."

She's a comedian and actor, a showbiz type herself, and remains her brother's closest confidant.

There were six Sedaris siblings growing up in suburban Raleigh, North Carolina. A typical middle class household, that is until you flipped the page as it were, and ventured inside.

David Sedaris: It just felt like-- we weren't sentimental. I don't know, it was almost like we were hard-bitten alcoholics children.

Amy Sedaris: "Hard-bitten."

Jon Wertheim: Wasn't corny, but it doesn't sound like you were arch or judgmental, either.

David Sedaris: Judgmental, yeah.

Amy Sedaris: Judgmental, for sure. If you're wearing a toe ring and you're gonna come to our house, then we will rip you to shreds.

Spend time with a Sedaris, you'll notice they share a certain sensibility. A legacy of their mother, Sharon, who also gave them their first lessons in storytelling.

David Sedaris: Something would happen and she'd get on the phone, and then tell a friend about it. And then she'd get on the phone a while later and tell another friend. And you'd think, "Oh, it changed," you know? Like the story--

Amy Sedaris: She'd work the story, which is where he gets it from, you know?

David Sedaris: And then she would do it again, and again, and again. And by the end of the day, she had this little, polished gem. But I do that same thing. Like, Amy never does that. Amy never repeats herself.

Amy Sedaris: Oh, yeah, I do, yeah, I do.

Their father, Lou Sedaris, they say, was never quite in on all the stories and jokes and could be cruel to his children, particularly to David.

David Sedaris: I just feel like my dad bet all his chips on me being a failure. You know, my father said a million times, "You know what you are? A big, fat zero." I mean, how many times did dad say that to me?

Amy Sedaris: Yeah, a lot--

David Sedaris: "And everything you touched turns to crap." I mean, over and over and over and over again.

Jon Wertheim: You heard this--

David Sedaris: And so, as a kid, I thought, "You know what? I'll show you." But you never show them.

David's early years were a struggle. He wrestled with obsessions and compulsions and with his father's refusal to accept that he was gay. He drank too much and dropped out of college —twice— before finally getting a degree in visual arts. In the early 90s, sedaris moved to New York, where he took a series of odd jobs, chronicling his life in a diary, but publishing no essays until he wrote about his time working as a department store Christmas elf. He read us an excerpt.

David Sedaris: There was a line for Santa and a line for the women's bathroom. And one woman after asking me 1,000 questions already, asked which is the line for the women's bathroom. And I shouted that I thought it was the line with all the women in it. And she said, "I'm gonna have you fired." I had two people say that to me today, "I'm gonna have you fired." Go ahead, be my guest. I'm wearing a green velvet costume. Doesn't get any worse than this.

Jon Wertheim: Let-- let's be clear, you-- you didn't take this job as an elf for-- for irony, or because you thought you were gonna write about it one day?

David Sedaris: No. I don't have any skills. I applied for all sorts of jobs-- and I got this job because I'm short. You know? I'm short and I didn't have a criminal record.

In the history of unlikely literary breaks, this might take the prize. What started as a journal entry became a National Public Radio essay, "Santaland Diaries," which, when it aired in 1992, did the equivalent of going viral.

Jon Wertheim: This would be your breakout hit? This is what put you on the map?

David Sedaris: Yeah.

Jon Wertheim: Did you know that at the time?

David Sedaris: No. Nope. It just seemed like everyone was listening to the radio that day. And it really-- I went from somebody -- with no opportunities to someone-- having to weed them out.

Since then, his subject matter expanded, but his form has remained consistent. No novels or sweeping narratives. He starts with a notebook he brings everywhere and turns the jottings into personal essays, that mix memory, observation and, he admits, some exaggeration in service of humor. The final product usually begins with the mundane and ends with the meaningful.

And while the literary celebrity may be an endangered species, Sedaris not only plays the part, but dresses the part. He contributes essays to the New Yorker, the BBC and, on occasion, CBS News. And at age 65, he is on the road more than 200 days each year, good for his brand, but also his process, he writes for the ear as much as for the reader's eye, which makes audiences not simply his fans, but his most important editor.

David Sedaris: The audience isn't wrong, right? You can't convince some-- somebody that something is funny. Either they laughed at it or they didn't. Either they paid attention to it or they didn't. And the audience is telling you all of that. so it's my job to listen to them.

For all his success, his approach to the job can still leave him feeling like an imposter.

David Sedaris: That's when I worry, though, because I think, "Well, what if I'm not really a writer?" Because-- what if I'm-- you know, there's certain ways you can cheat with your voice. Right? You can make your voice--

Jon Wertheim: You-- you really have that concern? A dozen plus books into this, millions and millions sold, you really have that, "I'm-- I'm not a writer?"

David Sedaris: Yeah, because look I'm cheating here. Look. I-- I'm saying-- "He's afraid of a woman. Angela repli–" "A woman." I'm not describing her voice. I'm doing her voice. Right? So can-- can a reader hear her? Right? Or am I cheating? Am I cheating by using my voice?

Still, his readings drive book sales, which drive ticket sales, a virtuous cycle that's afforded Sedaris multiple homes, including a cottage in southeast England where he spends part of the year with his partner of more than 30 years, Hugh Hamrick, an artist who appears in many essays as the sensible, centering ballast, to David's flights of fancy.

David Sedaris: In my mind it's sort of a classic domestic story, one character is, you know, kind of hapless and the other person is reliable and capable. And that's Hugh all over, right? I don't know how to do anything. I don't know how to look at our bank statements online. I don't open any envelope unless it looks like fan mail.

Hamrick hates the limelight as much as Sedaris craves it, and it took some convincing to get him to sit down with us. We wondered what it was like living with someone for whom everything is a potential story.

Jon Wertheim: Do you have any veto power? "Whoa, whoa, whoa, I-- I don't want this one--"

Hugh Hamrick: I think he would know what I'd accept and what I wouldn't accept.

Jon Wertheim: You've never had to say, "No, no, no, no. This can't go out to the readers of The New Yorker or the millions of people reading your books?"

Hugh Hamrick: I think I mighta tried a few times just saying, "Do you have to say that?" He says, "Yeah, everyone thinks it's funny." And I was like, "Okay."

These days going for the biggest laugh can be risky, especially for someone like Sedaris who, proudly, doesn't much traffic in boundaries.

Jon Wertheim: Are you sensitive to "Man, this is gonna make me look bad when people read this?"

David Sedaris: Everything is such a landmine now. I don't wanna sit at my desk with my hands and feet tied together.

Jon Wertheim: "You offended me."

David Sedaris: "You offended me." I-- I think, "Great. There is other stuff for you to read. Go somewhere else."

Out here in England, far from the Twitter mob, mornings are for writing, while afternoons are for going on walks or, well, remember we mentioned Sedaris's childhood compulsions? The adult version, he says, is this: picking up trash on the side of the rural roadways. We naturally wanted to tag along.

Jon Wertheim: How many hours a day?

David Sedaris: Between four and six usually. I go out-- after midnight I'll go out-- I know, it sounds so crazy.

Jon Wertheim: You'll go out after--

David Sedaris: I go out with a headlamp on and do busier roads.

This is also where he says he does a lot of thinking, which recently has centered on his father, Lou, who died last year. Their unhappy relationship left unresolved, David wrote about one of their last conversations.

David Sedaris: Then he turned to me: "David," he said, as if he'd just realized who I was. "You've accomplished so many fantastic things in your life. You're-- well, I want to tell you, you-- you won."

Jon Wertheim: When he said, "You won," you think it was this cosmic, "You won the game of life?" Or do you think it's, "You won-- you defeated me"?

David Sedaris: I'd go back and forth. I mean, that's what-- part of what made it compelling to write about, is that I don't know. That's a question I'll be asking myself, I don't know, for the rest of my life.

Produced by David M. Levine. Associate producer, Elizabeth Germino. Edited by Patrick Lee.