Life after a wrongful conviction: The challenges of one man's newfound freedom

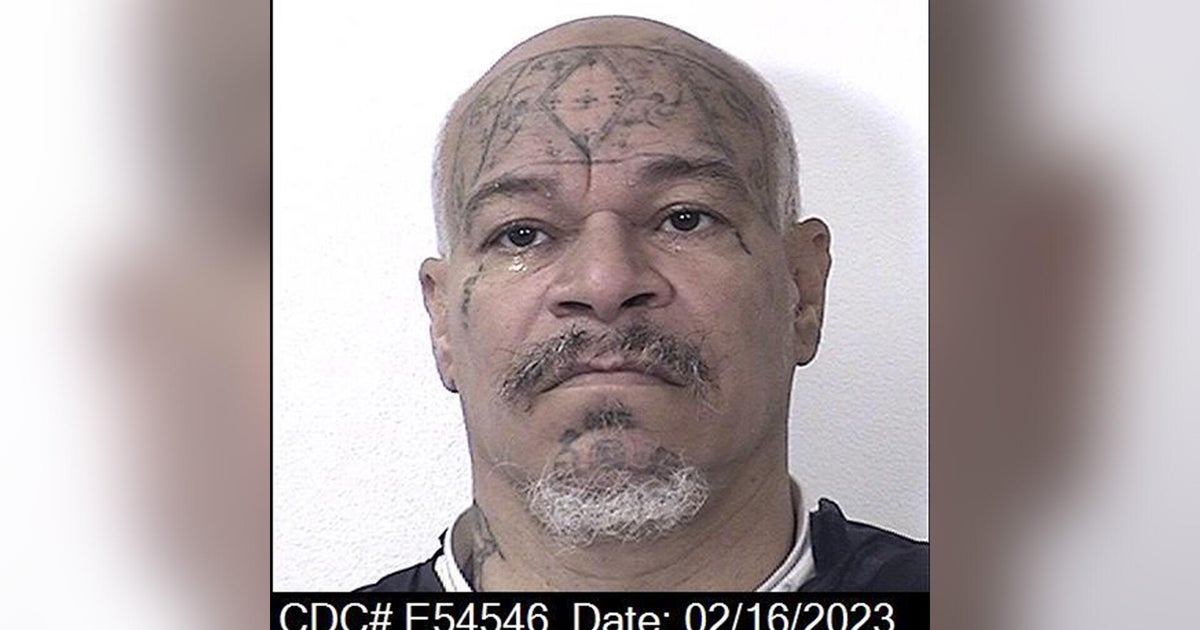

More than 2,000 inmates in the U.S. have been exonerated and released from prison since 1989. On May 15, David Robinson joined them and walked out of a Missouri prison.

Robinson had been given a life sentence, but the Missouri Supreme Court overturned his murder conviction.

So what happens when wrongly-convicted man goes home after nearly two decades in prison? Inmates who are paroled get help with housing and finding employment, but if you are innocent and get released, you are often on your own.

Today, Robinson, who went into prison at 32 and is now 50 years old, is in a world he no longer recognizes. Getting back his life has been tougher than he expected.

"When David was first arrested, Bill Clinton was president and Amazon was a book company," Robinson's lawyer Jonathan Potts says.

Potts says when Robinson was released, he had to completely start over.

"He had no money in his pocket. He didn't have a home," Potts said. "He didn't have credit. Essentially you're being reborn."

One month after his release, Robinson walked down the aisle, cheered on by his lawyers, family and friends. He married longtime girlfriend Pat Jackson who never gave up on him during the 18 years he was incarcerated.

"She could have probably moved on. In fact, I asked her to, but she wouldn't," Robinson said.

She wasn't sure this day would ever come, Robinson had been serving life for the 2000 murder of young mother Sheila Box. There was no physical evidence tying Robinson to the crime, just the testimony of two government informants who later admitted they lied. In 2004, another man, Romanze Mosby, confessed to shooting the victim during a botched drug deal.

This past February, a special master appointed by the Missouri Supreme Court ruled what Robinson had been saying all along: that he was an innocent man.

Robinson and his wife now live in Sikeston, Missouri where Robinson is looking for a job, but applications are all online and it's a little slow going.

Jackson-Robinson, a nurse, says just getting her husband an ID card was a challenge. And a bank account?

"You can't have a bank account because you have to have your residence for six months established," Jackson-Robinson said. "And then you have the other hurdles. Like health insurance, one of the questions that they ask is have they been incarcerated? So you have a harder time getting health insurance."

And while Robinson has left prison, it hasn't quite left him.

"We were in a department store, shopping for something to wear, you know, to the wedding," Jackson-Robinson said. "He had paid for his stuff, but the clerk forgot to take off the sensor. And so once he went to the door the alarm started going off and so he threw his hands up in the air. His instinct was 'I didn't do it.'"

Robinson knows the odds of staying free are against him, but he's determined to beat them.

"Well, like grandpa said, you could call me a young fool, but you ain't gonna call me an old fool," Robinson said. "So I'm gonna start the rest of my life, livin' it differently than I did the other part of my life."

For inmates in Missouri freed because DNA tests prove their innocence, there are state funds.

But for Robinson, released after a judge determined a detective bungled his case, there is nothing.