Cryptocurrency "miners," utilities look for ways to get along

Electric producers aren't sure whether cryptocurrency "miners" are friend or foe.

The miners, who use powerful computers to generate bitcoin, ethereum and other cryptocurrencies by solving complex computational problems, are power hogs that can bring new sources of revenue for energy producers. But that revenue generally comes at a price: millions of dollars of investment in new power stations and lines.

For their part, utilities hesitate to commit those funds for fear the bottom will fall out of the cryptocurrency market, leaving them stuck with the bill for facilities no longer in use.

- Cryptocurrency: Virtual money, real power, and the fight for a small town's future

- Watch: Making money off your data

- Watch: Should the U.S. get rid of cash for cryptocurrencies?

"Getting power companies to take cryptocurrency mining seriously has been a struggle," said JohnPaul Baric, chief executive of the MiningStore, which makes cryptocurrency mining technology. "Mining is still in its early days, and power companies say they aren't sure of its longevity."

It's not as if the power companies don't want the additional revenue. But in the case of Grant County in Washington State, more than 100 cryptocurrency miners are requesting power. Combined, they are asking for 1,700 megawatts of new power -- that's the equivalent of two nuclear power plants, or 1.5 times the power needs of the city of Seattle. Grant PUD's average electric load is about 600 megawatts.

"We, like any other utility, aren't set up to handle that kind of new demand," said Kevin Nordt, general manager for the Grant County Public Utility District, known as Grant PUD. "Trying to get that kind of infrastructure built would take many, many years and require millions if not billions of dollars in investment. There's a lot of risk involved because it's an nascent industry with a lot of unknown variables."

Cryptocurrency miners use large numbers of computer servers – which use massive amounts of electricity -- to solve complex mathematical puzzles needed to create virtual currencies like bitcoin and ethereum. Bitcoin miners alone use more power than the entire country of Ireland. There are more than 2,000 different types of cryptocurrencies.

Grant PUD's popularity with cryptocurrency miners stems in part from its low price for electricity generated from power plants on the Columbia River, Baric said. Electrical expenses are often the highest costs for cryptocurrency miners.

"We are the most power-intensive business ever – we use crazy amounts of power," Baric said. "Electricity costs matter."

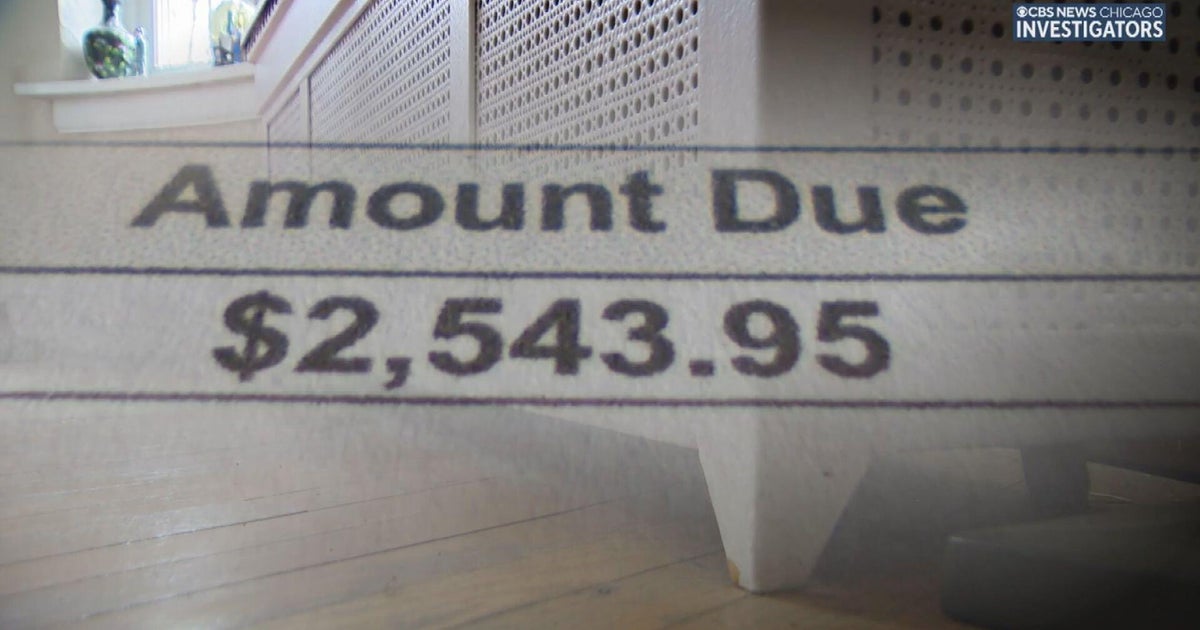

The average cost of electricity in the U.S. is about 12 cents per kilowatt-hour. But Grant PUD sells its electricity for only 1 to 2 cents a kilowatt-hour, Baric said. Grant PUD is a nonprofit, community-owned hydropower utility based in Moses Lake, Washington, about three hours southwest of Seattle. Its power generation facilities cover 2,800 square miles.

Because of the intense demand, Grant PUD temporarily stopped accepting cryptocurrency mining customers so that it could develop new policies around the industry. The PUD decided to create a new customer class called the "evolving industry" class. The class wasn't meant only for cryptocurrency, but for any other radical, disruptive type technology that may take shape in the future, Nordt said.

The evolving industry class would price in the risk associated with creating new infrastructure for an industry without a long track record, he said.

"We needed to look at this differently," he said. "We don't know how regulatory and other issues are going to break for mining."

Miners, in the meantime, are also suggesting ways they can be of benefit to utilities. One example is for miners to use a utility's "peak load" capabilities that often sit idle. Most utilities build their facilities so they have capacity even for those very hot days in July and August, when everyone is running their air conditioners.

The miners could use that unused peak load capabilities throughout the year and stop mining when the utility needed the extra electricity on those hot summer days. Baric sells products that would automatically shut down the mining operations when the peak load was used.

"The actual physical mining units would just sit there idle and the staff would have the day off," Baric said. "The miners would know for those four or five hours on that hot July day, they will be disconnected."

Miners are also happy to take extra, unused electricity off the hands of producers, Baric said. Utilities inevitably create more energy than they use and generally allow that power to be burned off. Miners are instead willing to buy that access energy which is a benefit to producers, he said.

"Years ago people wondered if the internet would stay around, but suggesting that today would seems silly," Baric said. "That's the way it is with cryptocurrency; it's brand knew and people don't yet understand it yet. But it's here to stay."