U.K.'s COVID variant hunters warn undetected mutations could be widespread in U.S.

London — British scientists say the fast-spreading COVID-19 variant first discovered in southern England is evolving in a way that could make existing vaccines less effective against it. The U.K. has kept a close eye on mutations of the coronavirus for months, leading the world in tracking changes in the genetic code of the virus.

Authorities in England are trying to test everyone over the age of 16 in many neighborhoods where a few cases of yet another troubling variant — the one first detected in South Africa — have been found. But even as Britain races to find and stop that highly infectious strain, scientists discovered that the U.K. variant appeared to be mutating in a way that mimics the South African one.

The discovery has elevated concerns about the virus' continuing evolution, which some evidence suggests could lead to resistance to the vaccines being rolled out across the globe.

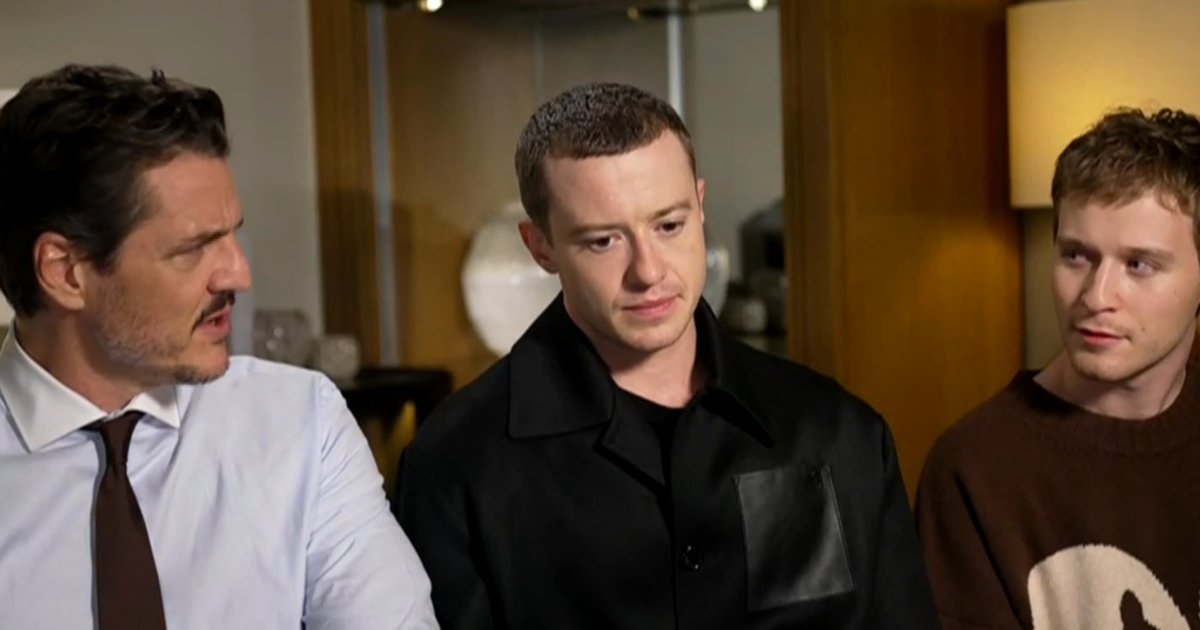

"The virus, over time, is improving itself," Sharon Peacock, who leads a nation-wide network of British scientists tracking the transformations more closely than anywhere else in the world, tells CBS News correspondent Roxana Saberi.

For the coronavirus, Peacock, a professor of public health and microbiology at the University of Cambridge, says, "It's a matter of natural selection. It's the survival of the fittest."

She tells CBS News that her team at COVID-19 Genomics UK hunts every day in labs across Britain for any new mutations, which "really give us a barcode for the virus."

That hunt relies on both robots and human researchers, at sites like the Wellcome Sanger Institute near Cambridge, poring over thousands of samples of COVID-19, mapping mutations in the virus' genetic code.

In November, they spotted something alarming: Mutations, many in the spike protein of the virus, that were allowing it to latch onto cells more tightly, making it much more contagious.

Whereas 10 people infected with the old variants of the virus could be expected to pass it on to 13 others, 10 people carrying the new variant discovered in Kent, southeast of London, could infect around 20.

"That's really important," says Peacock, "because more people can get sick and therefore more people are likely to die simply from the burden of disease."

Quickly dubbed the "U.K. variant," the new strain has since swept across the world, prompting the U.S. and many other nations to tighten their travel restrictions. Germany and Austria now mandate anyone venturing out into most public places to wear medical-grade masks, not just cloth face coverings, and the U.K. has imposed a third nation-wide lockdown.

Scientists in the U.K. say that as COVID-19 continues to mutate, the rest of the world also needs to do more genetic sequencing — and the U.S. has some catching up to do. Right now less than 1% of coronavirus samples in the U.S. are being sequenced, compared to around 10% in the U.K., meaning many dangerous mutations may be missed.

Peacock says it's "very likely" that COVID-19 variants in the U.S. are more widespread than currently known, "and I think that sequencing is going to be vital in detecting that."

Ravi Gupta, a professor of clinical microbiology at the University of Cambridge, tells CBS News that vaccines will likely need to be redesigned by the end of this year to adapt to new mutations. A senior researcher for pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca said on Wednesday that that work would be done "as rapidly as possible."

"We're working very hard and we're already talking about not just the variants that we have to make in laboratories, but also the clinical studies that we need to run," Mene Pangalos said during a media briefing. "We're very much aiming to try and have something ready by the autumn, so this year."