Three scientists give their best advice on how to protect yourself from COVID-19

Over the past several months, there has been controversy over the way SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, travels from an infected person to others. While official guidance has often been unclear, some aerosol scientists and public health experts have maintained that the spread of the virus in aerosols traveling through the air at distances both less than and greater than 6 feet has been playing a more significant role than appreciated.

In July, 239 scientists from 32 countries urged the World Health Organization (WHO) to acknowledge the possible role of airborne transmission in the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Three days later, WHO did so, stating that under certain conditions, "short-range aerosol transmission, particularly in specific indoor locations, such as crowded and inadequately ventilated spaces over a prolonged period of time with infected persons cannot be ruled out."

Many scientists rejoiced on social media when the CDC appeared to agree, acknowledging for the first time in a September 18 website update that aerosols play a meaningful role in the spread of the virus. The update stated that COVID-19 can spread "through respiratory droplets or small particles, such as those in aerosols, produced when an infected person coughs, sneezes, sings, talks or breathes. These particles can be inhaled into the nose, mouth, airways and lungs and cause infection. This is thought to be the main way the virus spreads."

However, controversy arose again when, three days later, the CDC took down that guidance, saying it had been posted by mistake, without proper review.

Right now, the CDC website does not acknowledge that aerosols typically spread SARS-CoV-2 beyond 6 feet, instead saying: "COVID-19 spreads mainly among people who are in close contact (within about 6 feet) for a prolonged period. Spread happens when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks, and droplets from their mouth or nose are launched into the air and land in the mouths or noses of people nearby. The droplets can also be inhaled into the lungs."

The site says that respiratory droplets can land on various surfaces, and people can become infected from touching those surfaces and then touching their eyes, nose or mouth. It goes on to say, "Current data do not support long range aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2, such as seen with measles or tuberculosis. Short-range inhalation of aerosols is a possibility for COVID-19, as with many respiratory pathogens. However, this cannot easily be distinguished from 'droplet' transmission based on epidemiologic patterns. Short-range transmission is a possibility particularly in crowded medical wards and inadequately ventilated spaces."

Confusion has surrounded the use of words like "aerosols" and "droplets" because they have not been consistently defined. And the word "airborne" takes on special meaning for infectious disease experts and public health officials because of the question of whether infection can be readily spread by "airborne transmission." If SARS-CoV-2 is readily spread by airborne transmission, then more stringent infection control measures would need to be adopted, as is done with airborne diseases such as measles and tuberculosis. But the CDC has told CBS News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jonathan LaPook that even if airborne spread is playing a role with SARS-CoV-2, the role does not appear to be nearly as important as with airborne infections like measles and tuberculosis.

All this may sound like wonky scientific discussion that is deep in the weeds — and it is — but it has big implications as people try to figure out how to stay safe during the pandemic. Some pieces of advice are intuitively obvious: wear a mask, wash your hands, avoid crowds, keep your distance from others, outdoors is safer than indoors. But what about that "6 foot" rule for maintaining social distance? If the virus can travel indoors for distances greater than 6 feet, isn't it logical to wear a mask indoors whenever you are with people who are not part of your "pod" or "bubble?"

Understanding the basic science behind how SARS-CoV-2 travels through the air should help give us strategies for staying safe. Unfortunately, there are still many open questions. For example, even if aerosols produced by an infected person can float across a room, and even if the aerosols contain some viable virus, how do we know how significant a role that possible mode of transmission is playing in the pandemic?

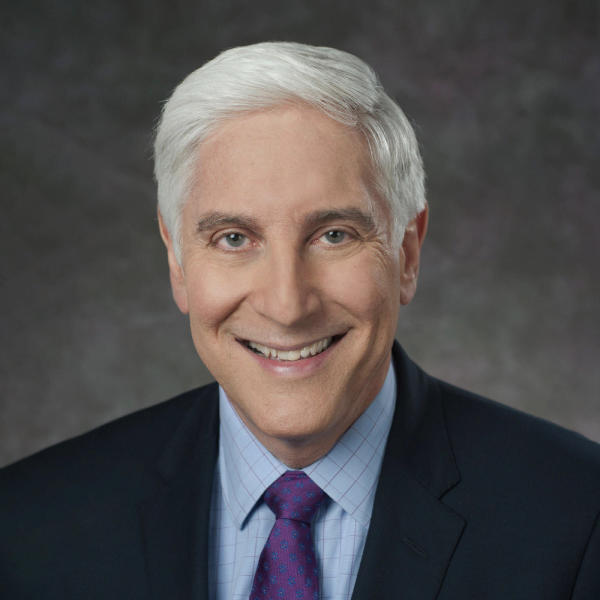

As we await answers from ongoing research, Dr. LaPook turned to three leading scientists to try to clear the air. Acknowledging that the science is still not set in stone, they have generously agreed to give us their best advice on how to think about protecting ourselves, based on their current understanding of the way SARS-CoV-2 can spread.

Below, atmospheric chemist Kimberly Prather, airborne virus expert Linsey Marr and environmental health professor Donald Milton discuss the best precautions you can take to reduce your risk of infection.

Clearing the air

In contrast to early thinking about the importance of transmission by contact with large respiratory droplets, it turns out that a major way people become infected is by breathing in the virus. This is most common when someone stands within 6 feet of a person who has COVID-19 (with or without symptoms), but it can also happen from more than 6 feet away.

Viruses in small, airborne particles called aerosols can infect people at both close and long range. Aerosols can be thought of as cigarette smoke. While they are most concentrated close to someone who has the infection, they can travel farther than 6 feet, linger, build up in the air and remain infectious for hours. As a consequence, to lessen the chance of inhaling this virus, it is vital to take all of the following steps:

Indoors:

Practice physical distancing — the farther the better.

Wear a face mask when you are with others, even when you can maintain physical distancing. Face masks not only lessen the amount of virus coming from people who have the infection, but also lessen the chance of you inhaling the virus.

Improve ventilation by opening windows. Learn how to clean the air effectively with methods such as filtration.

Outdoors:

Wear a face mask if you cannot physically distance by at least 6 feet or, ideally, more.

Whenever possible, move group activities outside.

Whether you are indoors or outdoors, remember that your risk increases with the duration of your exposure to others.

With the question of transmission, it's not just the public that has been confused. There's also been confusion among scientists, medical professionals and public health officials, in part because they have often used the words "droplets" and "aerosols" differently. To address the confusion, participants in an August workshop on airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine suggested these definitions for respiratory droplets and aerosols::

Droplets are larger than 100 microns and fall to the ground within 6 feet, traveling like tiny cannonballs.

Aerosols are smaller than 100 microns, are highly concentrated close to a person, can travel farther than 6 feet and can linger and build up in the air, especially in rooms with poor ventilation.

All respiratory activities, including breathing, talking and singing, produce far more aerosols than droplets. A person is far more likely to inhale aerosols than to be sprayed by a droplet, even at short range. The exact percentage of transmission by droplets versus aerosols is still to be determined. But we know from epidemiologic and other data, especially superspreading events, that infection does occur through inhalation of aerosols.

In short, how are we getting infected by SARS-CoV-2? The answer is: In the air. Once we acknowledge this, we can use tools we already have to help end this pandemic.

Kimberly A. Prather, PhD, Distinguished Chair in Atmospheric Chemistry, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego.

Linsey C Marr, PhD, Charles P. Lunsford Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Virginia Tech.

Donald K Milton, MD, DrPH, Professor of Environment Health at The University of Maryland School of Public Health.