Court rules against Education Secretary Betsy DeVos in for-profit college case

Education Secretary Betsy DeVos' move to delay Obama-era protections for students defrauded by for-profit colleges was dealt a setback when a federal judge found her actions to be "arbitrary and capricious."

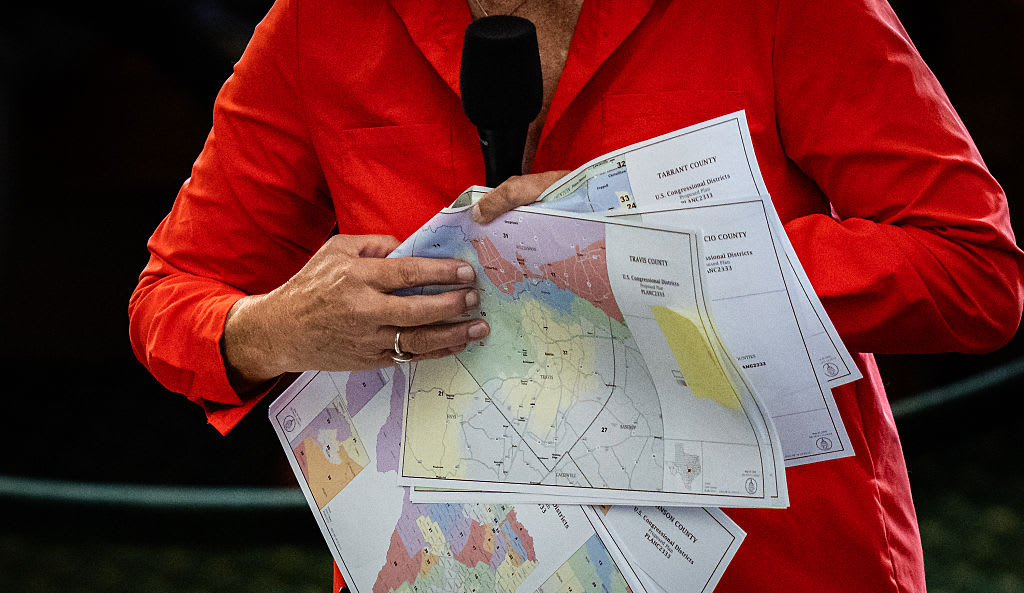

U.S. District Judge Randolph Moss ruled Wednesday in a lawsuit challenging the delay that had been filed by Democratic attorneys general from 19 states and the District of Columbia and former students, finding that DeVos' actions were unlawful.

The case centered on the borrower defense rule, which allowed defrauded students to have their student loans forgiven. The rule was to have taken effect on July 1, 2017. DeVos had argued those rules created "a muddled process that's unfair to students and schools."

But Moss found inconsistencies in DeVos' rationale for freezing the rule.

"When an agency decides to delay the effective date of a rule to save the federal government money or to alleviate confusion or a burden on regulated parties while the agency decides whether to amend or to rescind the rule, its action is 'designed to implement ... policy,'" Moss wrote in his decision .

He said DeVos acted without conducting a rule-making process on whether to postpone the rules. Moss scheduled a hearing Friday to consider next steps.

Department of Education spokeswoman Liz Hill said the agency was reviewing the ruling.

Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, who led the lawsuit, said the ruling was "a victory for every family defrauded by a predatory for-profit school."

Toby Merrill, a litigator at Harvard University's Project on Predatory Student Lending, which represents defrauded students, hailed the decision as "a huge a rebuke to the department."

"It's a really big deal, it's an incredibly important win for student borrowers and really for anyone who cares about having a government that operates under the rule of law as opposed to as a pawn of industry," Merrill said.

After two decades to rapid growth, the for-profit college industry was shaken by the implosion of two major chains of schools that misled students with promises they couldn't keep and left them with large amount of debt they couldn't pay. The Obama administration went hard after the sector, issuing regulations meant to increase student protections and police the schools.

In trying to delay the borrower defense rule, Devos said the regulations were too broad and allowed for potential abuse on the part of students. She vowed to create a new system that would be more efficient and fair.

But critics dismissed the freezing of this and other regulations as an attempt by DeVos to promote industry interests. They point to the fact that DeVos has hired for-profit industry insiders to top position at her agency.

Rick Hess, director of education policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, would not comment on the legal aspects of Wednesday's ruling, but called it "substantively an unfortunate decision."

Hess said the Obama regulation "gives blanket forgiveness to students who may or may not have been mistreated or defrauded in any way, it puts taxpayers on the hook for potentially large payouts for people who were not misled and suffered no harm."

"I think what DeVos is doing is trying to be a responsible steward who is trying to strike a healthier balance between protecting students and ensuring that taxpayers don't get ripped off."

Merrill said she hopes the judge will rule that the delayed rules must now take effect. If that happens, she said, students would win some important protections: not having to sign away their right to sue the school, getting loans automatically discharged if their school was closed mid-program and if they were unable to transfer their credits to a similar program, and being eligible for forbearance when applying for loan discharges.

DeVos also put in place a new system of compensating defrauded students for their losses. In a break with the Obama administration's practice of fully forgiving student loans, DeVos in December rolled out a new tiered relief system, in which students' loans are forgiven based on their earnings.

That practice was frozen as part of a separate lawsuit. It was uncertain whether Wednesday's court ruling would have any effect on the tiered relief system.