Could your DNA help solve a cold case?

Do you know your third cousins? What about your fourth?

Chances are you may have never met them — or even know who they are. But your DNA could be used to catch them in a crime.

This week on 60 Minutes, correspondent Steve Kroft reports on a powerful new law enforcement tool called genetic genealogy. It compares the DNA of an unknown suspect left at a crime scene with DNA from family genealogy databases to find, if not a direct match, a distant relative that may lead to one. It's the first clue genetic genealogists use to identify a suspect.

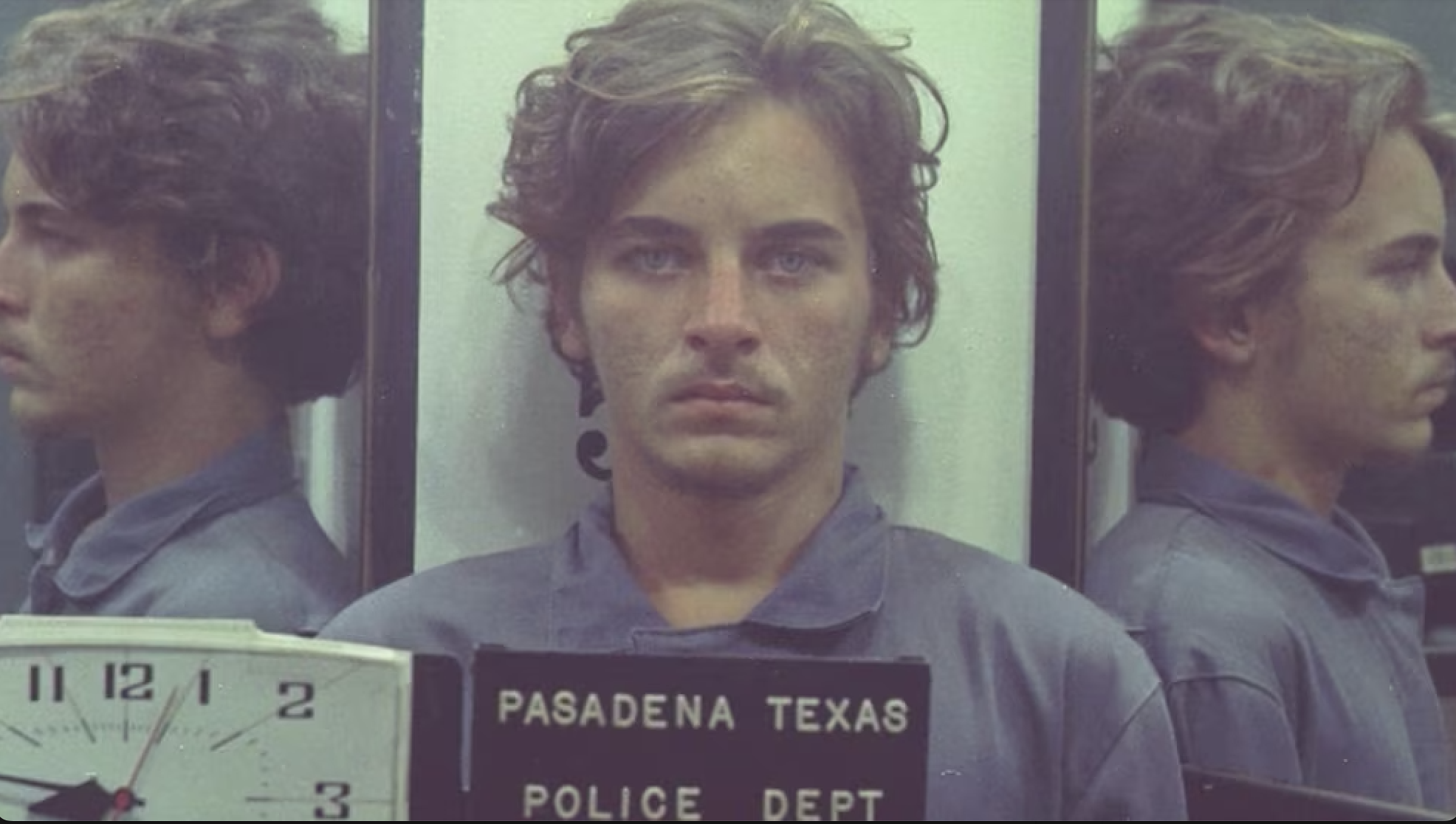

Law enforcement agencies around the country say they have used the technique at least a dozen times to crack cold cases, including arresting the man they believe is the Golden State Killer, a suspect that had frustrated law enforcement for decades.

In the case of the Golden State Killer, investigator Paul Holes uploaded the killer's DNA to an obscure public database called GEDmatch, a site popular with genealogy enthusiasts for finding family members. It worked. After months of research, detectives say they figured out exactly who left the DNA behind at rapes and murders 40 years ago.

After the case broke, news came out that GEDmatch had been the catalyst. Users on the site didn't seem to mind the thought that their DNA may be used for crime solving; the number of DNA kits uploaded to the site has remained steady since police released the information.

"I think that most people would say, 'Fine, I'll sign on for that if it helps catch a serial killer,'" Kroft tells 60 Minutes Overtime's Ann Silvio in the video above.

They may help, but they'll likely never know. Kroft says people whose DNA helps inform an investigation will probably never find out that their genetic information helped crack a case.

The report may have viewers wondering: If law enforcement could potentially access their genetic information, should they willingly give it up to a website? Kroft notes that commercial sites like 23andMe and Ancestry.com have strict privacy standards, and they don't make their databases available to law enforcement without a subpoena.

GEDmatch, however, is a different case. Many people who upload their data to GEDmatch originally had their DNA analyzed by companies like 23andMe or Ancestry.com, then uploaded it to GEDmatch to see if they could find a family connection they that didn't turn up in the other searches. Because GEDmatch is public, law enforcement can access the database by uploading DNA from a crime scene to see if they get family matches.

Kroft says the decision whether or not to upload personal DNA may come down to whether or not you've got proverbial skeletons in your closet.

"I think some of it probably has to do with whether or not you have anything to hide," he says. "If you have something to hide, then probably it's a good idea not to upload to Ancestry, and 23andMe, and GEDmatch."

But even if you choose not to, your distant cousin may. And because law enforcement is virtually unanimous in their support of using a DNA database to solve decades-old crimes, the technique may take precedent over users' privacy concerns.

"Who is going to be the person who is going to say to the family of those victims, 'No, I'm sorry, we can't do this,'" says Michael Karzis, the 60 Minutes producer who produced this week's story. "The horses have left the stable. I don't think they're going to go back in."

The video above was produced by Ann Silvio and Lisa Orlando. It was edited by Lisa Orlando.