What are "super" antibodies? Doctor explains cells found in less than 5% of COVID-19 patients

Researchers in California have identified what they are calling a super-strength antibody that blocks the coronavirus' most infectious elements. The discovery comes amid an international race to find a vaccine, which internal medicine specialist Dr. Neeta Ogden warns "may not be perfect" in terms of immunity from the disease.

"What is important for researchers is to see how we can effectively use these neutralizing antibodies now that we know what they do," Ogden told CBSN anchors Vladimir Duthiers and Anne-Marie Green.

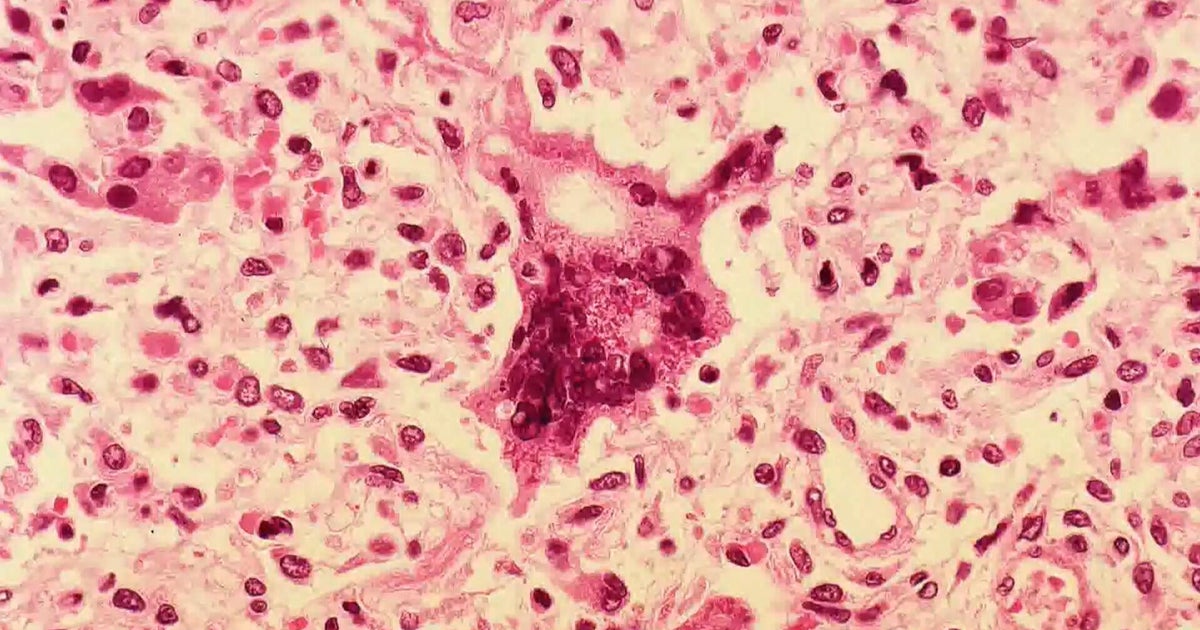

The neutralizing antibodies, or "super" antibodies, work by targeting what is known as the spike protein of the coronavirus, Ogden said. Named for its spike-like appearance, the protein populates the outside of the coronavirus and is "essential" for the virus to attach itself to human cells.

"These neutralizing antibodies effectively keep the virus from entering human cells and could essentially knock out the infection," Ogden explained.

Non-neutralizing coronavirus antibodies are found in 75% of patients. Neutralizing antibodies are only found in fewer than 5%.

The scarcity of these antibodies is leading researchers to try and clone the cells responsible for producing them in the hopes of mass producing the particles in order to re-inject them into sick patients, Ogden said.

While researchers have figured out the antibodies occur 11 to 21 days post-infection, it is still "not clear" how long they remain active, Ogden said.

"The problem is we don't know enough about how these neutralizing antibodies work in terms of how long they last," Ogden said. "What levels do we need to have a protective immunity, and do they prevent reinfection?"

Cloning the antibodies is a step in the push for vaccine development. Ogden said it remains to be seen whether a vaccine will be able to produce the neutralizing antibodies, and what levels are needed to "produce durable immunity."

Ogden warned it would be "very realistic" to expect the first version of a vaccine to not act as a "complete prevention of infection."

Some early vaccine candidates tested on animals have not been foolproof in terms of immunity, but have prevented "infection in the lungs" and "horrible severe pneumonia."

"Perhaps a vaccine means that you get a more mild infection, maybe just a cold. Maybe a very, very milld sinus infection," she said. "It prevents you from ending up in the hospital with that severe pneumonia eventually, or that really severe disease."