Inside an American coronavirus containment zone

Coronavirus is the greatest disruption to American life since 9/11. Efforts to contain the spread are triggering a cascade of cancellations, travel bans and the threat of a recession. As of this afternoon, there were about 3,000 known cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., but responsible, conservative, estimates say many millions of Americans may become infected. The idea behind the restrictions is to let that happen over the course of a year, not in a matter of weeks. For a preview of what might be coming to your community, we went to a hotspot: Westchester County, New York. The spread, there, began two weeks ago when an infected 50-year-old man went to a religious service, a funeral and a party. Since then, he's been in a hospital, too ill to speak. That has propelled teams of courageous nurses to visit hundreds of homes on the frontline.

- COVID-19: New York's health care system contingency plans

- Fighting coronavirus: What we can do... together

Westchester County is home to a million residents, about a half hour's drive from America's largest city. Chevon Jones, Caitlin Doyle-Goldsmith, and Cathy Gomez are nurses in the county department of health. They're suiting up to enter the home of a couple who had contact with that first patient. A few minutes before they put on their equipment, they had introduced themselves on the doorstep.

Chevon Jones: I want people to see who I am first. It's very important. I want them to see my face before I put on all the equipment. So, we go, knock on the door, introduce ourselves. "We're from Westchester County Health Department. We're nurses. We're here to do the testing."

Cathy Gomez: When this first started, we would ask them also, "Do you want us to go around the back so that your neighbors don't see this and they don't get alarmed." But then as it started becoming more public they were--

Chevon Jones: They were okay.

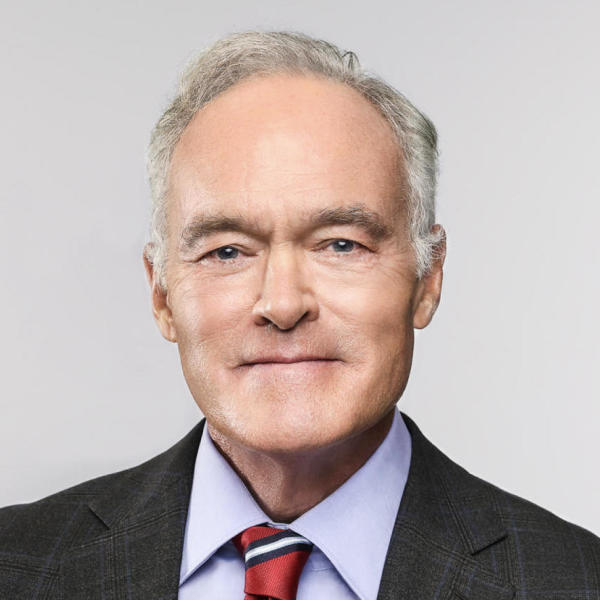

Scott Pelley: How do people react to your visits?

Cathy Gomez: Grateful. That's all I can say. They're all kind, grateful.

Scott Pelley: Not fearful?

Cathy Gomez: Not fearful. Not fearful at all of us.

The nurses collect one swab from the nose and another from the throat. A few days ago, the swabs were being carried by state troopers, three hours, to the only lab in New York certified to do the tests. Since then, another 28 labs have been approved.

Scott Pelley: What are some of the questions, Chevon, that you get from these families that you're visiting?

Chevon Jones: The number one question is, "When will I have my test results? When will I be off of quarantine?" You know, a lot of them was, like, "Is there a letter that you can give to me for my employer?"

The answers are up to three days for the results, 14 days in quarantine, and a patient can show his employer the official quarantine order left by the nurses.

Scott Pelley: There must be people who say, "Oh, I can't be quarantined for 14 days. I have a business trip to Detroit next week." And you tell them?

Cathy Gomez: You must.

Scott Pelley: You must.

Caitlin Doyle-Goldsmith: We're asking you to stay home for 14 days, also pending the results of your labs. We're asking you not to go to work, not to go to school, not to go food shopping. Really, just to stay home. If you need to get a breath of fresh air, you're allowed to go in your backyard, but don't go within six feet of anyone.

This past week, the governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, closed Broadway theaters and all venues with more than 500 seats. He ordered bars and restaurants to operate at half capacity.

Andrew Cuomo: We have to get down the rate of infection. And the only two ways to do that is test, test, test, find the positive, isolate the positive, stop the contagion by reducing the density. Just reduce the ability of the virus to spread.

Scott Pelley: From the early data, it appears that the vast majority of patients have mild symptoms. So why is it important to take these severe measures?

Andrew Cuomo: If we did nothing, yes, 80% would contract the virus. They would self-resolve. Some people would require hospitalization. And we could overwhelm the hospital system and those vulnerable people who needed the intensive care wouldn't get it.

But part of the cost is an economic crisis. Markets rose Friday, but not before the Dow Industrials suffered its most rapid fall from a record high to a bear market since November, 1931—The Great Depression.

Scott Pelley: The airplanes are flying empty. I was at JFK Airport yesterday. It was almost abandoned, it looked to me. You have cut the capacity of every restaurant in New York City in half. These are real costs to the economy.

Andrew Cuomo: What value do you put on human life? What value do you put on human life? And we say here it's invaluable. And if you say, "Well, we're gonna lose 5,000 more people." I say close the restaurants. I say close the stores. I don't wanna lose 5,000 more people. If you do not slow the spread, the health care system can be overwhelmed. And more people will die.

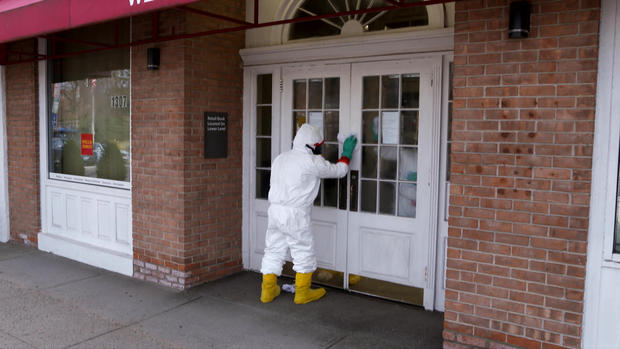

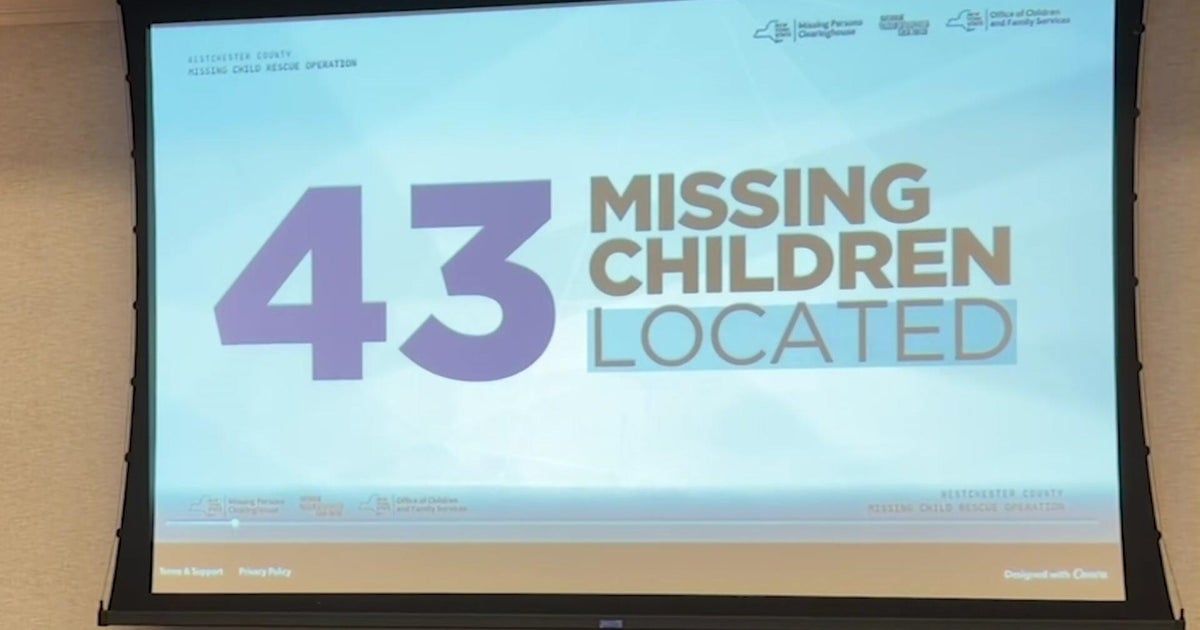

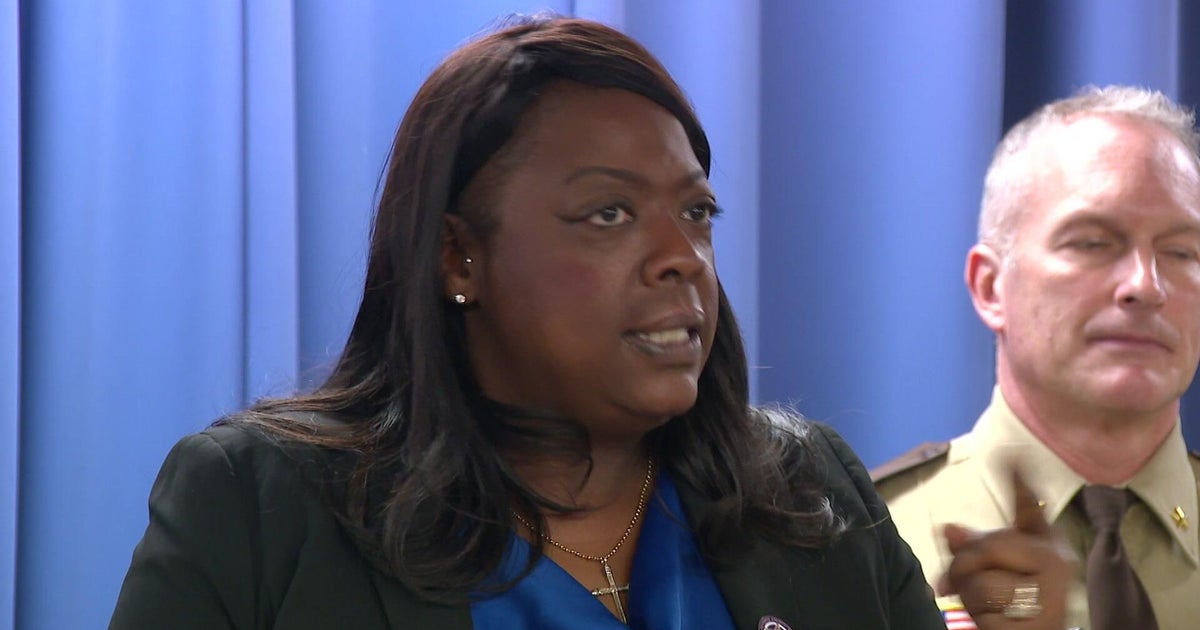

New York state spent $30 million just this past week on its virus mobilization. In Westchester County, 60 nurses and EMTs are dispatched from a center hastily set up by the state in vacant office space. They're pulling in staff from 20 state agencies, including forest rangers. When we were there, 222 homes had been visited, 639 were waiting with more added all the time. County health commissioner Dr. Sherlita Amler told us investigators are questioning everyone who may have had contact with that first patient.

Dr. Sherlita Amler: Where have they traveled to? What do they do for a living? Who do they work with? Where do they work? What kind of work do they do? If there are children in the family, where do they go to school? Then, what about their social life? Were they at any parties? Did they go to any business organizations' meetings? Did they travel?

In Italy there were too many patients too fast. The hospitals were overrun. This is what Amler is trying to avoid. Slowing the virus in America buys time.

Dr. Sherlita Amler: Why do we need time? Because we do not have a vaccine currently to prevent this disease. We do not have an antiviral to treat this disease. So, if we can slow it down and there are fewer people infected, we'll have fewer deaths.

Most of Westchester County's quarantined are in the city of New Rochelle. Here, the state has imposed what it calls a "containment zone."

Mayor Noam Bramson: it is primarily residential.

Mayor Noam Bramson told us the center of the zone is the synagogue visited by that first patient.

Mayor Noam Bramson: So the containment zone has a one-mile radius. To be very clear, because there's a lotta confusion about this-- it is not a quarantine zone. It's not an exclusion zone. It is an area in which large gatherings within large institutions are prohibited.

Which means no gatherings of more than 50 people.

Mayor Noam Bramson: So it effects schools, both public and private. That's houses of worship. It affects the local country club. It doesn't have an effect on residents, it doesn't have an effect on businesses. No one is prohibited from entering or leaving. It's not as though this area's on lockdown.

Maybe not the 'area,' but this lock is on the gate of New Rochelle's high school. The nearby middle school is being sanitized.

Tamar Weinberg: It's very difficult when you have young children, but, yeah…

Tamar Weinberg had contact with the county's first patient. She's quarantined at home.

Scott Pelley: How old are your children?

Tamar Weinberg: Three, five, seven, ten.

Scott Pelley: How long have you been behind the gate here?

Tamar Weinberg: For a week.

Scott Pelley: What is that like?

Tamar Weinberg: A little stir crazy, but thankfully I love them, so we're good, we're good there.

Scott Pelley: I'm usually much friendlier than this is ten feet or so and we're told that's what we have to do in order to avoid any contact.

Tamar Weinberg: Right.

She shot pictures for us of her online life. Online school for the kids, online support from the community.

Tamar Weinberg: The community at large has-- they've been amazing at just offering to do any types of errands, shopping for us. And what they do is they come to our house. They drop off food at our doorsteps.

Scott Pelley: What are you gonna do the first day you can open the gate?

Tamar Weinberg: I'm gonna go to the gym. I'm gonna run. running around in circles around my driveway, even though it's nice and all, I almost die of boredom.

Friday, the state opened a drive through testing center in New Rochelle. Swabs are passed through the window, nose and throat samples are passed back out. The driver will get a call in a couple of days. The state hopes to process 6,000 tests a day.

By this morning, Westchester County reported tests on more than 1,300 people, of those 14% have come back positive, so far, 4,000 in Westchester County have been under quarantine. George Lattimer is the county's top elected official.

Scott Pelley: When you have someone in a mandatory quarantine for 14 days what if they don't have 14 days-worth of groceries? What if they don't have their prescription drugs?

George Lattimer: That's our job. Our job is to figure out how to get them the food that they need. If there are medicines or anything else under the sun, you know, any of the necessities of life, we have to figure out how to deliver that.

Lattimer is also thinking ahead to a worse case.

George Lattimer: Civil unrest is always a possibility depending on how large a group you have to quarantine. So, the real question is how many more New Rochelles will we see in the nation? How large will this get? And will government at every level, from the federal government on down, be prepared to deal with these things?

Nothing seems normal. Even in preparing for our interview with Governor Cuomo at the state capitol

The New York Department of Health required we sit 10 feet apart because the state is monitoring the 60 Minutes office where several colleagues have the virus. After the interview, one of the governor's daughters went into self-isolation after being near someone who might have been exposed.

Scott Pelley: It's bound to get worse?

Andrew Cuomo: It will get worse. It will get much worse before it gets better.

Scott Pelley: Can you imagine a quarantine of New York City?

Andrew Cuomo: No. I can't imagine a quarantine of New York City. I can imagine additional density reductions. We're at 50% occupancy. Italy went to closing stores entirely besides-- grocery stores and pharmacies. I think actually the more successful you are early on, the less dramatic efforts you have to take later on.

Scott Pelley: When does this end?

Andrew Cuomo: Months. Months.

Scott Pelley: We have been following public health nurses in Westchester County who are putting on all the protective gear, going into the homes of people who are believed to be infected. I wonder what you think of their effort.

Andrew Cuomo: God bless them. God bless them. God bless them. I marvel at their courage and their dedication. You can't pay a person enough to do that. It's a character statement of who they are.

Scott Pelley: You know, a lotta people watching what you do would think that it's heroic.

Chevon Jones: This is what public health is and so this is what we do. This is our job.

Caitlin Doyle-Goldsmith: For me, I think you feel like the whole community is your patient.

Scott Pelley: You know, I'm curious, knowing what you know, what do you tell your own families?

Cathy Gomez: Wash your hands.

Caitlin Doyle-Goldsmith: Maybe no unnecessary travel. Don't go to big events if they could be avoided.

Chevon Jones: You know, there's panic out there. And it's really, like, I tell 'em, "Until I become hysterical, don't really worry."

Scott Pelley: You're talking about being in these people's homes wearing those hazmat suits of your san saying don't be concerned.

Chevon Jones: Be concerned, but don't panic and don't be hysterical.

Produced by Guy Campanile. Associate producer, Lucy Hatcher. Broadcast associates, Ian Flickinger and Annabelle Hanflig. Edited by Warren Lustig.