Doctors in Italy find link between rare inflammatory disease in children and COVID-19

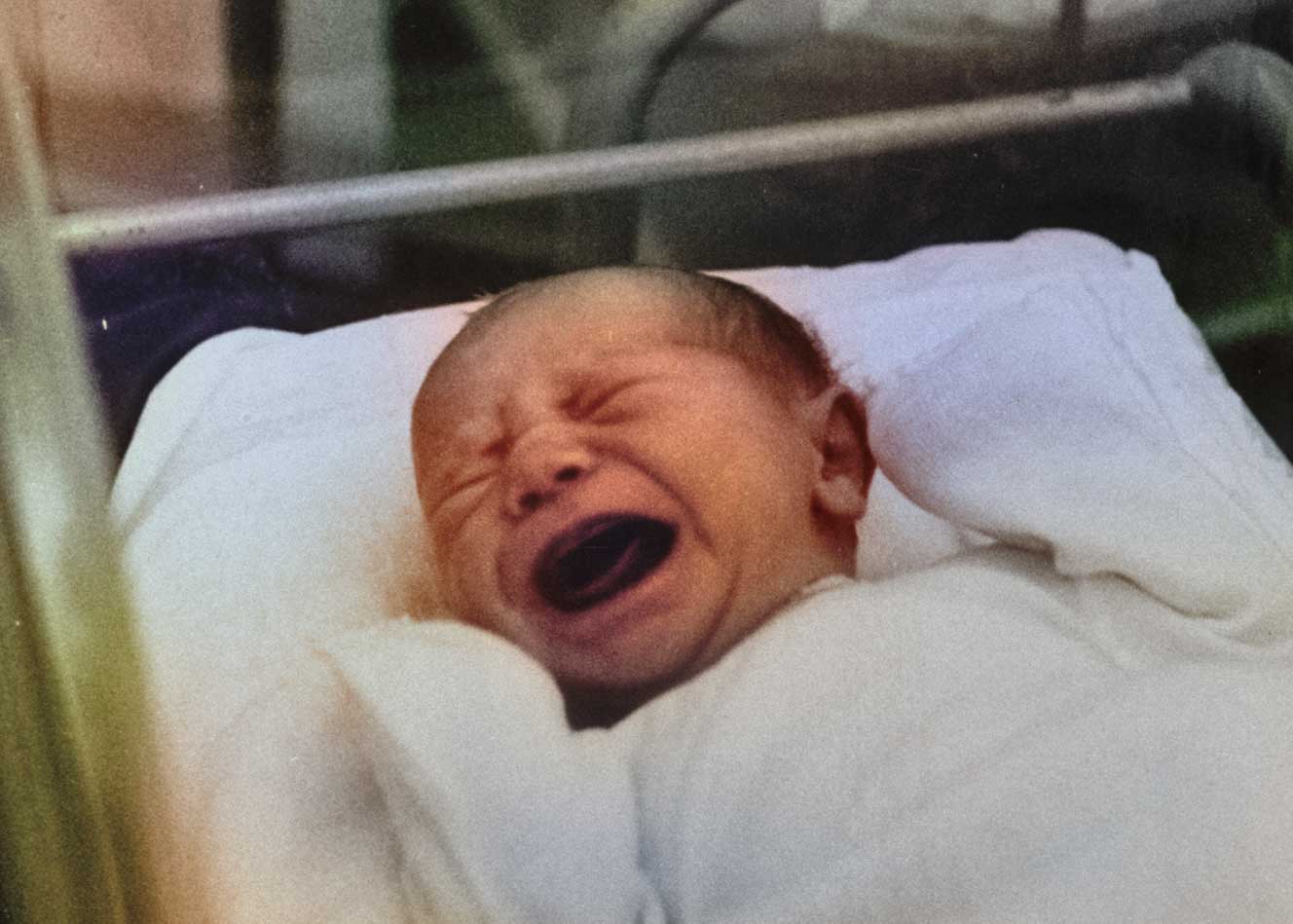

Rome — Italian doctors say they've got the first scientific evidence linking the coronavirus to a rare but deadly inflammatory disease in children. The condition, called pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome, has been reported in more than a dozen states across the U.S., including Louisiana, Mississippi, California and New York. Over 100 children have been affected in New York alone, three of whom died, according to Governor Andrew Cuomo.

Doctors had suspected early on that coronavirus played a role in the new disorder by triggering an excessive immune reaction, but there was no clear proof that the two were linked.

Reported in The Lancet medical journal, the new evidence comes from doctors in Bergamo, the epicenter of coronavirus infections and deaths in Italy, where the nationwide reported death toll is more than 30,000, behind only Britain and the United States.

Doctors at the Papa Giovanni XXIII hospital compared a series of 10 cases of the illness with cases of a similar rare condition in children called Kawasaki disease, finding a 30-fold increase in cases of Kawasaki-like disease in patients between February and April.

The acceleration of cases occurred at a pace of about one every three months, indicating a cluster that was fueled by the coronavirus outbreak, especially, the authors noted, since overall hospital admissions were much lower than usual during national stay-at-home orders.

"Our study provides the first clear evidence of a link between SARS-CoV-2 infection and this inflammatory condition, and we hope it will help doctors around the world as we try to get to grips with this unknown virus," said Dr. Lorenzo D'Antiga, director of child health at the hospital, in The Guardian.

None of the 10 children in Bergamo died, but the authors reported that their symptoms were much more severe than those of the children with Kawasaki disease. Heart complications were more common, as were lower counts of platelets. A type of white blood cell typical of coronavirus patients was also more prevalent.

Five of the children experienced shock, which did not occur in any of the Kawasaki patients.

The researchers also highlighted that eight of the 10 children tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies, indicating that the children had been infected with the virus weeks earlier. They suspect that the two other children may have been false negatives, due to imperfect tests.

While Kawasaki disease tends to strike infants and preschoolers, the 10 children with the mysterious disorder were generally several years older. The average age of the Kawasaki patients was 3; the average age of the children with this condition was 7 and a half.

The doctors warn that the "strong association" between the coronavirus and the inflammatory condition should be taken into account as governments around the world ease lockdown restrictions.

But they also stressed that the disorder is exceedingly rare, diagnosed in no more than one in 1,000 children exposed to the virus. Only a small fraction require intensive care, and even fewer die.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said it will soon issue an alert asking doctors to report cases of children with symptoms of the syndrome.