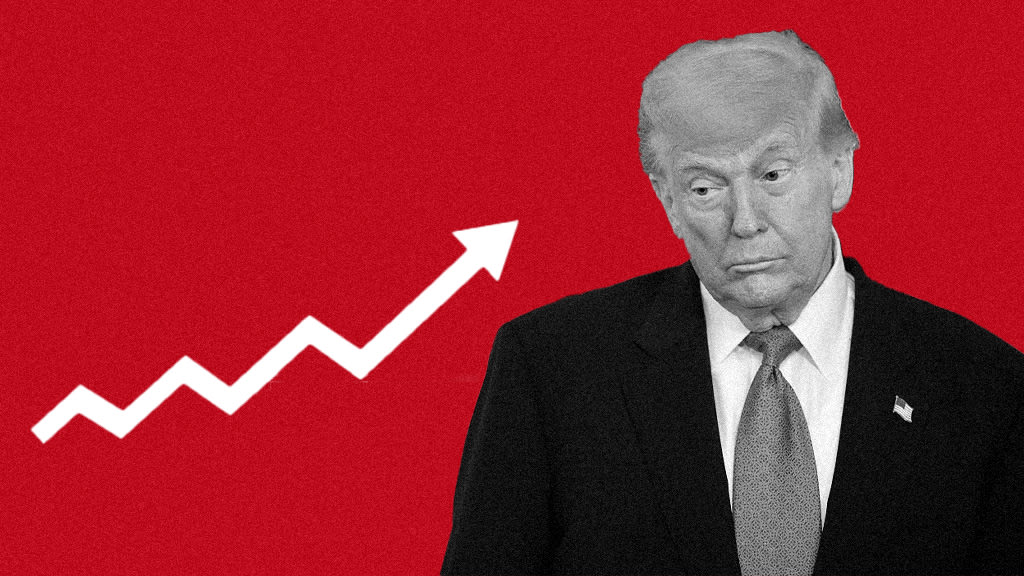

Consumer confidence index: Why Trump's favorite economic stat doesn't mean much

President Donald Trump is touting the growing confidence of the all-important American consumer, citing its rise toward an 18-year high as evidence of his administration's economic achievements.

"A big jump from last 8 years," he tweeted on Wednesday. "People are excited about the USA again! We are getting Bigger and Richer and Stronger. WAY MORE TO GO!" Mr. Trump has also previously said that how Americans feel about the economy "means a lot about jobs" and "means a lot about everything."

Is he right? Yes and no. Mr. Trump is correct in saying that Americans are generally optimistic about their economic prospects. The Consumer Confidence Index numbers released this week show that sentiment is approaching its highest level this century, and is within striking distance of the peaks it reached in 2000.

That's obviously good news in an economy largely driven by consumer spending. Happy shoppers tend to spend more; if someone is uncertain about the future, by contrast, they might be more inclined to save money and put off larger purchases. If enough consumers do this, spending will fall and slow down economic growth.

What such gauges of confidence data don't tell you is how long the good times will roll.

"The bottom-line question with these consumer surveys is, can they divine future household spending? Not very well, unfortunately," economic analyst Bernard Baumohl wrote in a textbook on the topic. "No methodology, mathematical construct, or statistical model can successfully predict how human beings will behave in a given circumstance," he added.

Nor are confidence measures all that useful to investors, according to Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer at Bleakley Advisory Group. After all, he pointed out in a recent note, Americans were feeling especially bullish in 2000, when the economy was also riding high -- and just before it slammed into a wall in the form of the dot-com crash.

Feelin' groovy?

Three main surveys are use to track the mood of consumers. There's the Consumer Confidence Index, issued by the nonprofit Conference Board. The survey is mailed to 5,000 families and asks people how they feel about business and employment conditions both in the present and six month in the future.

The Consumer Sentiment Survey, put out by the University of Michigan, asks similar questions, though the sample size is smaller. Then there's Bloomberg's Consumer Comfort Index, which every week asks a random sample of people about their finances, the state of the economy and whether it's a good time to spend money.

Despite such tools, economists have long debated whether assessments of confidence are particularly meaningful. A paper from the New England Economic Review, written a full two recessions ago, concluded that consumer sentiment doesn't have a great deal of predictive power when it comes to forecasting spending.

"The evidence suggests that sentiment is no more closely linked to expenditures in the 1990s than it has been in the previous 30 years," the authors wrote.

Still, there may be at least one reason to pay attention to sentiment—some analysts say it's an effective early warning when the economy is about to head south.

Consumer surveys are "really good at identifying turning points in the economy," said Brett Ryan, senior U.S. economist at Deutsche Bank. In other words, when a given confidence index is moving steadily up (or down), it doesn't mean much. But when public confidence is at a high point and then suddenly plunges, that can spell trouble.

For some professional readers of the economic tea leaves, that's a reason to take a more measured look at Americans' current exuberance.

"[E]xtreme levels of optimism are associated with impending recessions," Albert Edwards, an analyst with Societe Generale, wrote in a research note Wednesday, adding, "The U.S. consumer has gorged on optimism until they are fit to burst."