Psychiatrist: Colorado shooter never revealed violent plans

CENTENNIAL, Colo. -- The psychiatrist who treated James Holmes before he opened fire on the audience inside a Colorado movie theater said Tuesday that he had complained of homicidal thoughts, but never revealed any specific targets, plans or coherent reasons for carrying them out.

Patients sometimes talk about killing people, Dr. Lynne Fenton said. Therapists should determine if they have a plan: "If they're taking any steps to carry out any action that is related to these thoughts, and if the homicidal ideation is directed at any targets."

He answered "no" to both questions, she said, and this became an ongoing theme during their five sessions together after he came in showing what a social worker described as the worse obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms she had ever seen.

Holmes remained very guarded, deflecting most of her efforts to probe his thinking, and she tried not to ask him questions that would drive him away, she said.

"I thought he had social anxiety disorder," she said. "I was hoping to have a working alliance with him so he would keep coming back ... I was worried that he might drop out of treatment at any time."

At one point, Holmes said he had a "biological problem," and that the solution to it was homicide, "but you can't eliminate everybody, so it's not an effective solution," she said.

District Attorney George Brauchler asked if this eased her mind, and she said yes. But she remained concerned enough about his mental health to up his dosage to 150 milligrams daily of sertraline as well as klonopin and propranolol, she said.

The prosecutor repeatedly quizzed Fenton about whether Holmes revealed anything about the arsenal of weapons he was buying, the gas mask he would use, or whether he showed signs of depression, mania or suicidal behavior. She kept answering "no."

But he did show his temper, she said.

When Holmes couldn't refill his prescription at one point because she miswrote his name on the form, Holmes sent her an email with an emoticon that he said signified him punching her, to vent his anger for the inconvenience.

She apologized, but carefully noted the exchange.

By the time Holmes met with Fenton on May 31, he had already bought a gun and tear gas, but he didn't mention it. He did say that he hated "sheeple and shepherds," but Fenton said she didn't know what that meant.

During another session, "He angrily was asking me, 'Why won't you tell me what your philosophy of life was? I told you all of my ideas.'" Fenton's notes that day said Holmes might be engaging in "psychotic level thinking."

Defense attorneys say Holmes is schizophrenic and was in the grips of a psychotic episode as he carried out the July 20, 2012 attack. Two other psychiatrists appointed by the court to examine Holmes concluded he was legally sane when his gunfire killed 12 people, wounded 58 and left 12 others injured in the chaos.

In the end, Fenton saw Holmes five times in 2012 while he was a neuroscience graduate student at the University of Colorado. By pleading not guilty by reason of insanity, he waived his patient-client privilege and opened the door for her testimony.

Worried that Holmes wasn't communicating with her well, Fenton asked if she could bring in a second psychiatrist, Dr. Robert Feinstein. Holmes' reaction was, "Oh, it'll be to lock me up," but he eventually agreed.

Their final visit was on June 11, when he told Fenton and Feinstein that he had just failed his final exam and dropped out of the neuroscience program.

"Most students who failed a test like this would be very upset, and he seemed relaxed ... inappropriately nonchalant," she said. "We asked if he had a plan," and he described some logical steps, like meeting with an adviser and finding a job.

"It was all sounding like he was functioning well and looking forward to the future and had plans to get by," she said.

Fenton has directed the Student Mental Health Service at the University of Colorado's Anschutz Medical Campus in suburban Aurora since 2009. She oversees the psychotherapy and medication of 15 to 20 graduate students a week, teaches psychiatry and is a researcher with a particular interest in schizophrenia, according to the school's website.

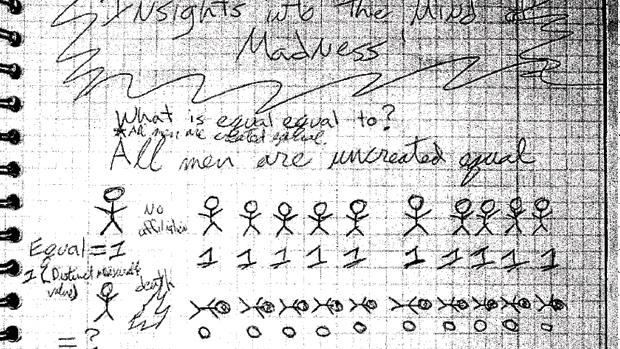

But Holmes said he pointedly kept Fenton uninformed of his murderous plots, and he quit seeing her when he withdrew from school more than a month before the attack. His elaborate schemes and to-do lists were kept in a journal that he didn't mail to her until hours before the assault.

That notebook - including $400 in burned $20 bills to show that he could no longer afford her therapy after withdrawing from school - lingered in a campus mailroom for days thereafter.

His list for their sessions included: "Prevent building false sense of rapport ... deflect incriminating questions ... can't tell the mind rapists plan."

Others have testified that Fenton contacted a campus threat assessment team in June 2012, and told a campus police officer about her concerns after the threatening email, but decided against the officer's offer to arrest Holmes and place him on a 72-hour psychiatric hold, according to a civil suit that accuses her of not doing enough to prevent the attack.

Two years after the shooting, Holmes told a court-appointed examiner, Dr. William Reid, that he kept Fenton in the dark. "I kind of regret that she didn't lock me up so that everything could have been avoided," he said in a video that was played for the jurors.