Colombia rebels' reintegration is focus of new U.N. mission

UNITED NATIONS -- The Security Council unanimously approved a resolution Monday authorizing a new U.N. political mission in Colombia to focus on reintegrating leftist rebels into society after more than 50 years of war -- a task the United Nations calls the most urgent challenge following the FARC rebels' handover of their last weapons.

A British-drafted resolution establishes the United Nations Verification Mission in Colombia for an initial period of one year starting on Sept. 17, when the mandate of the current mission that has been monitoring the cease-fire and disarmament process ends. It asks Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to make detailed recommendations on the size, operational aspects, and mandate of the new mission within 45 days.

Latin America's longest-running conflict caused at least 250,000 deaths, left 60,000 people missing and displaced more than 7 million. After years of thorny negotiations, the rebels reached an agreement with the government last year to transition into a political party, but serious differences remain over the peace deal.

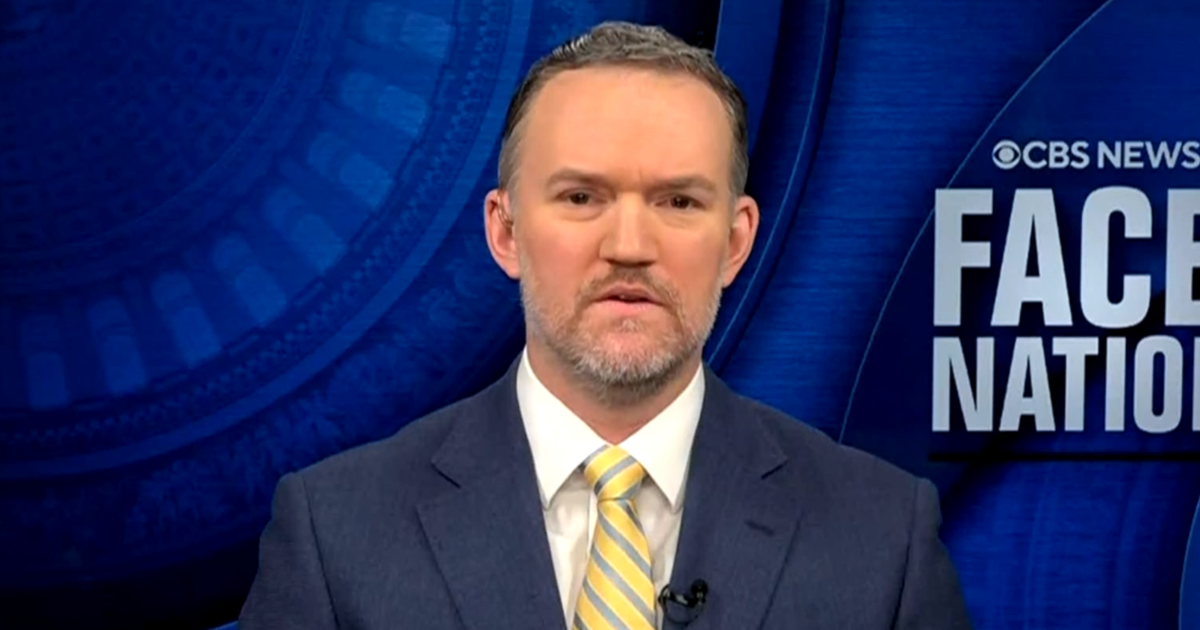

What still remains to be done is dealing with the other armed rebel groups in the country, CBS News' Pamela Falk reports, and that will have to be worked out for Colombia to be clear of civil conflict.

In January 2016, before the agreement, the Colombian government and rebels from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia known as the FARC jointly asked the United Nations to monitor any cease-fire and disarmament process, a rare request to the U.N. for help, which it accepted.

Last month, Colombia's President Juan Manuel Santos again sent a letter to the council on behalf of the government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia rebel group requesting a second political mission for three years, "renewable if necessary." The Security Council also visited Colombia in early May for a first-hand look at peace efforts and the U.N. mission.

Ten days ago, Jean Arnault, the U.N. special representative in Colombia, told the council the most urgent challenge is to reintegrate the 10,000 former combatants into society, a process that he said will be difficult.

Arnault said the FARC rebels have "a deep sense of uncertainty" about their physical security following their disarmament and their economic future.

Colombia's Foreign Minister Maria Angela Holguin said the peace process was developed by and for the Colombian people "so we can all have hope for a better future."

"However, it is surrounded by a dynamic debate, as happens in every strong democracy, but little by little, people are starting to notice the effects of peace and are willing to give it a chance," she told the council.

Britain's political counselor Stephen Hickey expressed delight that the Security Council responded swiftly to Santos' request for a new mission.

Hickey said the world has witnessed "an extraordinary journey in Colombia" that culminated in the end of the war. But Hickey said "experience from our own history in Northern Ireland has taught us that the hardest part remains ahead."

"A sustainable and lasting peace will depend on the FARC's successful reincorporation into civilian life," he said.

France's U.N. Ambassador Francois Delattre said the Colombian peace process "is a true success story" for the country but also for the U.N. and the Security Council.

"Now the goal is to win and entrench a lasting peace," he said. "And for that, the international community, the U.N., must continue to be at the side of Colombia."