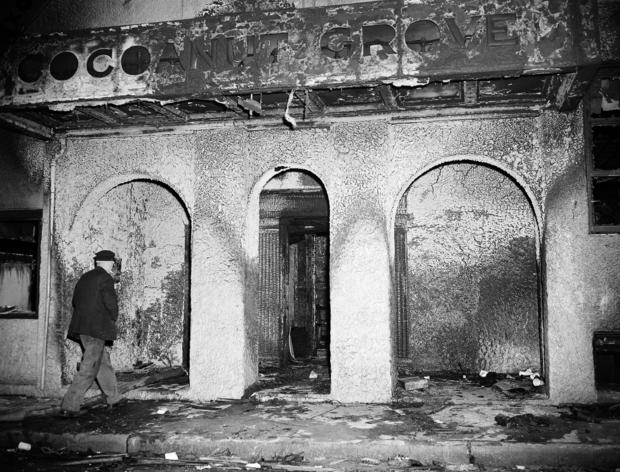

Deadliest U.S. nightclub fire influences safety codes, burn care

BOSTON -- In the blink of an eye the Cocoanut Grove — one of Boston's swankiest nightclubs — became an unimaginable inferno, trapping hundreds of panicked victims as they jammed the club's exits.

In less than 15 minutes, 492 people were dead and another 166 injured, making the blaze the deadliest nightclub fire in U.S. history.

While no one knows exactly how the fire started 75 years ago on Nov. 28, 1942, its influence on fire and safety codes and on the medical treatment of burn victims still resonates.

First flames

The fire started at about 10:15 p.m. as revelers packed the club near the city's South End on the Saturday after Thanksgiving, hoping to forget about the early days of World War II for a few hours.

The first flames broke out in a basement portion of the club, known as the Melody Lounge. From there, the fire rushed through the lounge and above the heads of people trying to race up a stairway, which acted as a chimney. A side exit door and a second door that opened onto a neighboring alley were locked.

Minutes after the first flames were seen in the lounge, the fire had reached the street floor lobby. The club was plunged into darkness when the lights went out, adding to the panic. A few people managed to escape before the front door became jammed, trapping hundreds.

Firefighters had the fire out in a little over an hour, but the horror was just beginning to dawn.

Cause unclear

An initial Boston Fire Department report written the day after the tragedy said the fire was "evidently" caused by a "young employee" who lit a match and accidentally ignited a fake palm tree.

From that day on, blame would most often fall on the shoulders of Stanley Tomaszewski, then a 16-year-old bus boy. Tomaszewski told investigators that he lit a match to help him change a light bulb hidden inside the tree, but immediately stamped out the match with his foot.

Some eyewitness accounts suggested the fire started in the ceiling, and others recalled the inside walls feeling hot even before any flames were seen.

Other possibilities have been examined, including shoddy wiring; gases from a refrigeration unit; and even vapors from the considerable liquor being consumed.

No official cause was ever determined and speculation abounds to this day.

Generations of Bostonians would also hear the story of a tragedy averted.

On the day of the fire, the Boston College football team was set to play rival Holy Cross College at Fenway Park with a postgame victory party planned for the Cocoanut Grove that evening. Boston College lost and the celebration was canceled.

Building codes

Anyone leaving a department store may have wondered why a central revolving door is often flanked by hinged doors on either side.

That's one legacy of the Coconut Grove fire, where so many died as they tried to exit the club's single revolving door.

The revolving door was only part of the problem. Adding to the death toll was the club's crowded conditions (with estimates of about 1,000 people in the venue when the fire broke out), locked doors and decorations that helped feed the flames.

Casey Grant, executive director of the Fire Protection Research Foundation, said the fire was a milestone event that prompted a national re-examination of fire prevention.

Massachusetts Fire Marshal Peter Ostroskey said the toughening of building codes — and ensuring they are enforced — may be the best tribute to the fire's victims.

"We have to make sure we are vigilant and follow those codes because they are based on experiences that we have gained sadly through tragedies like the Cocoanut Grove," Ostroskey said.

Treating the burned

After the fire, 166 people, many suffering burns, were rushed to two nearby hospitals — Boston City Hospital and Massachusetts General Hospital — offering a real world test of the treatment of burns.

Pearl Harbor had occurred a year earlier and the federal government had pumped money into Mass General for burn research.

The idea of blood banks and reserves of plasma was still relatively new, but Mass General had begun to build up its stocks, which were critical to reviving victims, according to Dr. John Schulz, medical director of the hospital's burn unit.

Schulz said, at the time, one of the preferred methods to treat victims was to paint burned areas with tannic acid. He said MGH decided, instead, to keep the victims as sterile as possible to avoid infections and to cover the burned areas with gauze and Vaseline. Victims were also given intravenous drips of antibiotics.

Schulz said the fire also prompted researchers to better understand the effects of smoke inhalation on the lungs, still something of a medical mystery.

"It got a lot of smart people interested in burns," he said.

Marking the site

There are few visible reminders of the fire, and that in itself has been a source of controversy over the years.

In 1993, a memorial plaque was placed on a sidewalk in the city's Bay Village neighborhood, at the site where the nightclub once stood, honoring "the more than 490 people who died as a result of the Cocoanut Grove fire on November 28 1942."

The plaque, however, was later moved about a block away to make room for luxury condominiums, angering some survivors and relatives of those who died.

In 2013, a small side street that now runs through the site was renamed Cocoanut Grove Lane.

The fire's embers

The blaze has continued to resonate through the years.

In 2004, then-Republican Gov. Mitt Romney signed into law a bill, which supporters called the state's toughest fire regulations since the Cocoanut Grove, requiring sprinklers in all nightclubs, bars, discos and dance halls with occupancy limits of 100 or more.

More than six decades after the Cocoanut Grove, however, a blaze at The Station nightclub in West Warwick, Rhode Island, killed 100 people, injured some 200 others and exposed troubling new gaps in fire protection protocols.

Combustible soundproofing material at the club was blamed for the rapid spread of the fire.

"It seems like every time we turn around there is some new issue, some new hazard that people didn't expect, people circumventing the requirements," said Grant. "We are safer in the United States than we were in 1942, but we still have a lot of work to do."