The heart of "The Cloud" is in Virginia

Plenty of us talk about "The Cloud," that enigmatic entity at the heart of the internet. But how many people really know anything about it? David Pogue of Yahoo Finance knows, and he takes us there in our "Sunday Morning" Cover Story:

These days, you can't walk through an airport, read a magazine or open a computer without seeing ads for "The Cloud." The ads clearly suggest that the Cloud is desirable. But what they don't say is what the Cloud is!

Well, here's the basic idea:

In the beginning, we all kept our own stuff on our own computers. In the new world of the Cloud, though, your computer files don't have to be on your computer; they can be stored out on the internet -- alongside everyone else's -- in huge, centralized buildings called data centers. Your computer or phone can then fetch your files on the spot, wherever you happen to be.

You may have encountered the Cloud as a synchronizing service. If you edit a photo on your Apple laptop, you see it a couple of seconds later the same way on your iPhone. There's no direct connection between the two devices. Instead, the data makes an intermediate hop.

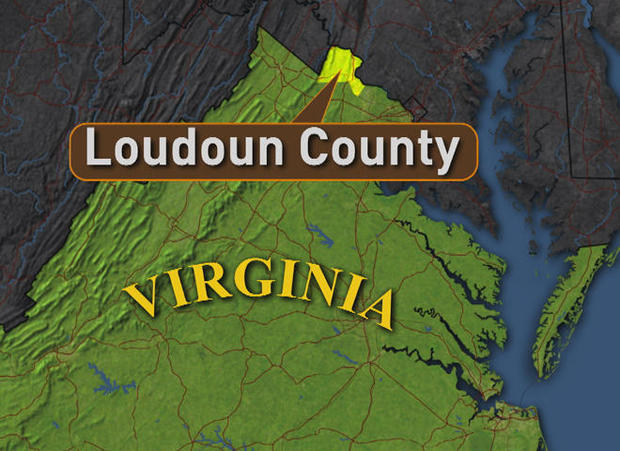

In a fraction of a second, it comes to a massive data center in Loudoun County, Virginia, and then goes to your phone.

Most of the time, though, you use the Cloud without knowing it, because most of those Cloud data centers exist to serve companies.

"It could be retail, it could be real estate, healthcare, life sciences, oil and gas -- everything from small initial startups right through to the very, very largest enterprises," said Matt Wood, a general manager at Amazon Web Services, or AWS. It's by far the biggest Cloud service company in the world -- bigger than its next 14 competitors combined.

So, what do all of these industries and companies hire AWS to do?

"Let's say you're a brewery," Wood said. "They don't want to manage computers; they want to brew beer. They don't want to be going through the expense and the upfront cost and all the complexity of managing these large amounts of computers."

"What you're saying is that Cloud companies like AWS are basically renting computers, storage, power, security, all the stuff that technicians would have normally had to do on site?" asked Pogue.

"That's right, yes. And so today, very large organizations such as GE, Shell, Phillips, Netflix, all run on top of AWS."

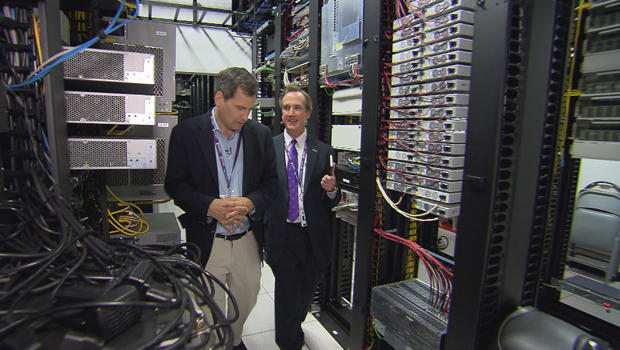

If you'd like to see what the Cloud looks like, all you have to do is visit a data center, like one belonging to RagingWire in Virginia. But good luck getting in! A retinal scanner will check your eyeball before letting you enter (and it will detect if the eyeball is still alive, in case you try to swipe a dead body).

"Well, darn, 'cause I was sort of hoping to kill you and sneak in," laughed Pogue.

"It's not gonna work here," said marketing director Jim Leach, who agreed to give Pogue a tour.

They had to pass through a "mantrap," in which one door has to close and lock before the next door could open.

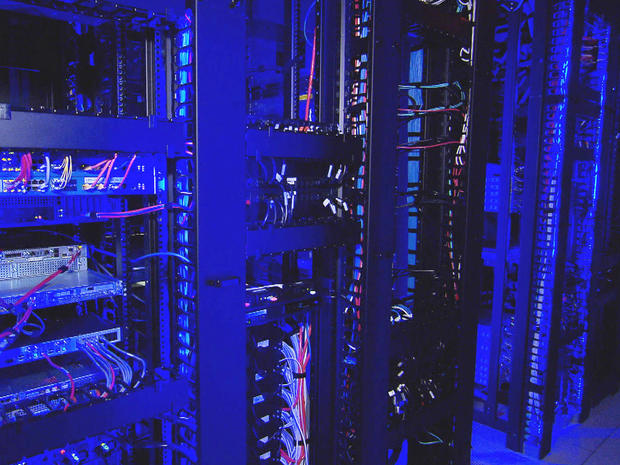

Once you get past the concrete barriers, the armed guards, the retina scanner, the mantrap, and nine password doors, you find out what's inside a data center: just racks and racks and racks of powerful computers.

This is the internet?

"This is the Cloud," Leach said. "Basically, in this room, ballpark, there's about three million websites running right now."

For security reasons, they'll never tell you whose websites. But every site and app you've ever heard of -- Facebook, Twitter, Netflix, Uber, AirBnB, The New York Times, even CBS News -- lives in data center cages like this one.

And what happens in a power failure? Leach said, "It's backed up by batteries that can run the entire facility for about ten minutes," as massive, diesel-powered generators are fired up.

This data center is in Loudoun County, Virginia. Buddy Rizer, the county's head of business development, helped turn Loudoun County into the largest concentration of data centers in the world -- 10 million square feet in 70 enormous buildings.

According to Rizer, 70 percent of all web traffic from the world, on a daily basis, passes through a Loudoun County data center.

"What do the data centers need?" Rizer said. "It comes down to power and water and fiber and workforce and proximity, and plenty of green space to build. Because these are really big buildings, as you can see."

But hold on a second: If we're concentrating all of our data into data centers, and concentrating most of the data centers in one county, doesn't that make a very tempting target for terrorists?

Amazon's Matt Wood isn't worried: "If something does happen or we have a power event or there's a flood in one specific location, that data is held redundantly in other locations as well."

Pogue asked, "I don't mean to give anyone ideas, but let's say I figured out that one of these unmarked buildings was an AWS data center, and I blew it up. Are you saying that it's so backed up and redundant that you probably wouldn't notice?"

"Yeah, you wouldn't notice. I mean, we might be a bit upset, but you wouldn't notice!" Wood laughed.

OK, so the Cloud offers speed, security, flexibility, and savings to the world's businesses. But that doesn't mean that there aren't skeptics.

"A really obvious example is that the Cloud uses a massive amount of power," said Tung-Hui Hu, a University of Michigan professor and author of "A Prehistory of the Cloud." "Greenpeace calculated that if you added up all these data centers, it would be the fifth-most power-hungry country in the world."

Amazingly, the Cloud is also often idle. "Data centers are just computers sitting around doing nothing for 96% of the time," said Hu. "And that's because they're waiting for a spike in traffic. They're waiting for the next music video to go viral. It's those exceptional moments which they have to build a capacity for it. But most of the time nothing really happens on the internet besides a lot of cat videos!"

And then there's all the secrecy. "We don't know anything about what Amazon or Google really does with their data," Hu said. "We have to take their word for it. In fact, if anything we sign away half of our rights to these data because the Cloud has the strange way of letting the companies decide what happens to the data that you have."

But even Professor Hu admits that the Cloud is here to stay. Amazon's AWS is on track to make $16 billion this year, dwarfing the part of Amazon that most people know, the part that sells books and things.

AWS is growing at 40 percent a year, and Loudoun County can't build data centers fast enough. Buddy Rizer says that seven new ones are under construction right now. A new RagingWire data center will add another two million square feet of data center space.

And even though it will be nearly two years until construction is completed, the space is already 100 percent leased. "It's not getting ahead; we're just barely keeping up," Rizer said. "There's no empty space in our data centers. By and large they are all 100% filled."

For more info:

- RagingWire Data Centers

- Amazon Web Services (AWS)

- Data Centers, at Loudoun County Economic Development

- "A Prehistory of the Cloud" by Tung-Hui Hu (MIT Press), in Hardcover, Trade Paperback and eBook formats; Available via Amazon