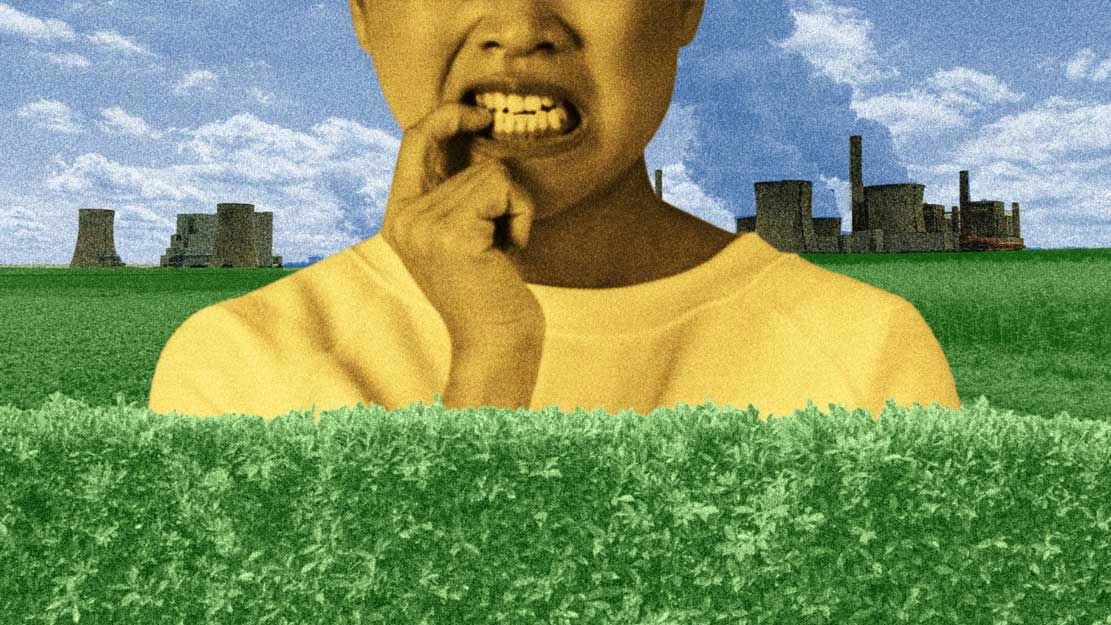

Climate change could mean more pesticides in your wine

- Climate change isn't just creating lower yields in vineyards, it's making them more susceptible to pests and mildew.

- Wine grapes native to Europe, including Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Riesling, are the least resistant to pests—and require the most pesticides.

- New York vintners are experimenting with native grapes that are more hardy—but those aren't as popular with drinkers.

Summer is the perfect time to sit outside and uncork a bottle of chilled white wine or Rosé. But drinkers who prefer European pours, watch out: Much more of it is likely to have been treated with pesticides.

The culprit? Climate change.

Too much greenhouse gas in the atmosphere has led to warmer springs and, in much of the temperate U.S. and in Europe, more humid air and more frequent rain. While warmer temperatures help grapes ripen faster, humidity makes them more prone to pests and diseases, like fungal diseases, mildew and cluster rot.

In Germany's Moselle region, prized for its Riesling, farmers are using more pesticides to cope with increased pests, Deutsche Welle reported. Pesticide use in the country increased from 2010 to today. There is little research on whether pesticides applied to grapes stick around in finished wine. A French study in 2003 found that most French wines contained at least one pesticide, although at levels that were too low to do damage.

More rain and more pests

Warmer temperatures aren't just a problem for European wine areas. In New York State, which produces much of America's Riesling, a destabilized climate means grapes bloom and ripen earlier. "On average, grapes are blooming seven days earlier than in the 1960s," said Tim Martinson, a senior extension associate in Cornell University's agricultural division.

However, it also means unpredictable cold snaps and extreme winters, such as the polar vortex in January. And those cold winters can kill grape vines before they have a chance to bloom. Severe frosts in 2014 and 2015 killed off a great deal of vines at Hunt Country Vineyards, a 38-year winery in New York's Finger Lakes region that emphasizes sustainable winemaking.

"In 2014, it went down to minus 18 degrees Fahrenheit during the vortex," said Suzanne Hunt, a winegrower and sustainability consultant. "We had enormous amounts of damage and very little harvest in our [European grapes] that year."

To head off future frosts, the Hunts have started laying vines along the ground and baling hay around them, keeping them above the minimum temperatures in cold winters. It's a laborious process that adds to the vineyard's costs, Hunt said.

Famous but delicate

European grapes‚ like Riesling, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc and Pinor Noir varieties, are better known and command higher prices -- but are also among the most delicate of thousands of grape varieties, showing susceptibility to cold and needing multiple doses of pesticides to stave off disease.

There is little research on whether pesticides applied to grapes stick around in finished wine. A French study in 2013 found that most French wines contained at least one pesticide, although at levels that were too low to do damage.

Hunt Country Vineyards has gone the opposite route of many conventional vintners, reducing its pesticide use in favor of better soil management through mulching and composting. The vineyard has installed a full complement of green-energy systems, including over 500 solar panels, geothermal heating and cooling and five electric car chargers.

In addition to its European-style grapes, the vineyard is also growing native North American and hybrid grape varieties that are more resistant to disease and cold than European counterparts. But getting consumers to accept them is another story.

"People go for names. People order chardonnay, they don't order white wine," said Martinson. "At Cornell we have an active breeding program, and we've developed some varieties that have an excellent wine quality, but they don't have the name."

Creeping northward

Climate change affects all wine-growing regions, not just the coolest areas. In places like California's Napa Valley, higher temperatures will make some areas too hot for wine cultivation. But it's also expected to open up wine growing possibilities in more northerly latitudes that were previously too cold to grow grapes.

"There are a number of wine producers and grape growers in countries like Norway and Sweden that weren't there before," said Damien Wilson, chair of the Wine Business Institute at Sonoma State University. Southern England is seeing an influx of wine producers, with a number of growers from France's Champagne region -- now too warm for reliable wine -- buying up land and planting grapes on the southeast coast of England.

While many growers find the thought of climate change unbearable -- "another thing they have no control over" -- a sliver of a silver lining is the possibility of expanding wine regions. "We're seeing more climates becoming wine growing-regions," Wilson said, "and you're seeing a lot of innovation."