"When temperatures do odd things...": How this map reveals a warning for the climate

No matter how you display it, for decades climate data has conveyed the clear and consistent trend of a rapidly warming Earth. But how a climate scientist chooses to visualize that data can really help to communicate vital clues about the climate system.

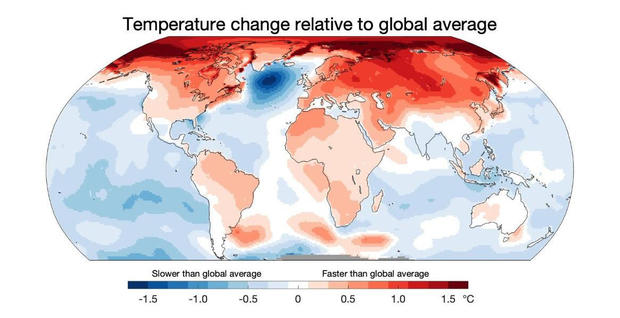

Recently, Ed Hawkins, the professor who created the now famous Warming Stripes visualization (read more about that here), from the University of Reading in the U.K. and the National Centre for Atmospheric Research, tweeted out a clever and eye-opening map, with shades of red and blue representing the amount of warming relative to other parts of the Earth.

Hawkins' color scheme focuses the eye on a few key spots with an important story to tell.

Below the dark red of the rapidly warming Arctic region, there's a big blue bullseye to the south of Greenland, in the North Atlantic, which is often called the "cold blob" or "warming hole." That dark blue bullseye, indicating cooling temperatures, might seem like an encouraging development on a warming planet, but it's actually quite the opposite — a warning sign that a vital linchpin in the climate system is malfunctioning.

"When I first saw this new image, it clicked in my head — wow! I knew it was a keeper that needed to be shown far and wide," said Dr. Jennifer Francis, senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Massachusetts. "So clear, so simple, so disturbing. It puts into a much clearer perspective how unevenly the Earth's temperatures are changing."

Both Francis and Hawkins say the stark contrast between red and blue in the same general area at high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere tells a story of a climate system out of balance. And they say it's all connected: The rapid warming is driving what might seem like an out-of-place cooling spot. But the cooling, they say, is not out of place at all — it is exactly what climate models expected.

It is related to the slowdown in the Gulf Stream System, also known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC — a vital system of ocean currents underpinning the global climate system.

The red is driving the blue

It's clear from Hawkins' map that the greatest warming on Earth is happening in the Arctic Circle area, where temperatures are rising at about 3 times the pace of the global average. Due to rapid warming, Arctic sea ice extent during its yearly minimum has been sliced in half. That floating sea ice does not contribute to sea level rise, but less ice means amplified warming — a warming feedback loop which quickens the pace of global warming.

It's this amplified warming of the Arctic that's causing Greenland's ice to melt 6 times faster than it did in the 1990s. This rapid ice melt from Greenland, scientists say, is what's responsible for that big blue bullseye of regional cooling in Hawkins' image. Here's how it happens.

When ice melts from Greenland, fresh water is flushed into the salty waters of the North Atlantic. Saltwater is dense, heavy, and sinks. But fresh water is lighter and does not sink as readily. This is throwing the Gulf Stream System out of balance. That is because the Gulf Stream System relies on cold, dense, salty water to sink in the northern Atlantic for "overturning" to occur, to drive the circulation and to keep it flowing.

The Gulf Stream is responsible for transporting about 20% of the excess heat gathered at the Equator towards the North Pole, as the Earth works to equalize the imbalance of heating between the tropics and poles. But since 1950, the Gulf Stream System has slowed down by 15% due to the freshening of the North Atlantic from ice-melt induced by human-caused climate change.

It is now moving at the slowest it has in at least 1,600 years, and research shows that the system will likely continue to weaken, perhaps slowing by 45% by the end of the century. This, in turn, may impact weather patterns such as heat waves and storms coming off the Atlantic.

"It is clear that the climate models have consistently suggested this would happen," Hawkins said.

"When temperatures do odd things in one place, you can bet that abnormalities of different sorts will happen in neighboring areas," said Francis. Research shows that this cold blob in the North Atlantic helps drive summer heat waves in northern Europe, heavy precipitation events in the U.K. and very warm waters off the U.S. East Coast.

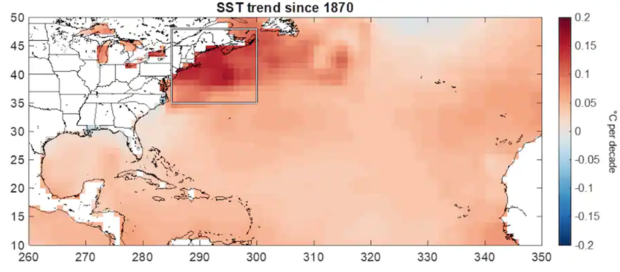

Dr. Andrew Pershing, the director of Climate Science at Climate Central and an expert on warming oceans, especially the Gulf of Maine, says the waters off the U.S. East Coast as a whole have warmed 3 to 4 times the global average over the last 30 years, and the region off the New England coast is warming faster than 99% of the rest of the ocean.

The warming of the waters off the northeastern U.S. coast, and more specifically in the Gulf of Maine, are a direct consequence of the slowdown of the Gulf Stream System. In the North Atlantic, that sinking water east of Greenland typically winds its way southwestward into the Gulf of Maine, known as the Labrador Current. That normally brings with it cold water. But as the North Atlantic freshens and the sinking lessens, the Labrador Current is losing its vigor, pumping less cold water southward.

Pershing says this regional warming has had a big impact on marine life in the region. "The waters off Rhode Island have warmed beyond the comfort zone of lobsters and the fishery there has declined considerably. On the flip side, warming has put Maine in the sweet spot for lobsters, and catches there have surged, at least for now," explains Pershing.

Furthermore, Pershing says cold-water species like codfish and right whales have been faring poorly as the waters off New England have warmed, but warm-water species like black sea bass are expanding northward.

It is not just marine life that is impacted. Pershing says the massive snowfalls that hit Boston during a cold snap in 2015 were likely made bigger by the fact that the ocean was unusually warm that winter. In fact, since 1970 snowfall in Boston has been trending upward, a possible side effect of a warmer ocean adding more moisture to storm systems.

It's also likely that hurricanes will be able to maintain more intensity farther north as they feed off of warmer waters caused by both the direct impacts of climate heating in the area and the slowdown of the Gulf Stream System.

Although a recent study found that by the end of the century there is some chance the Gulf Stream System could hit a tipping point, eventually leading to collapse, both Francis and Hawkins believe a full collapse of the system seems unlikely anytime soon.

"I think it is unlikely that the AMOC will undergo any sort of rapid 'collapse' but we can expect that the circulation will slow further and that the North Atlantic will continue to warm more slowly than most of the rest of the planet," Hawkins said.

Besides the big blue bullseye in Hawkins' visualization, there are some other features on the map that stand out. Hawkins points out that land is warming faster than the global average.

"Although we may talk about, say, 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) [of warming] globally, that really means 3 degrees C (or sometimes more) over land regions," he pointed out. And while a few degrees of warming may not sound like much, it's enough to be catastrophic to Earth's living systems.

Francis notes that the Northern Hemisphere land areas, in particular, really jump out as places warming much faster than the rest of the globe. And because humans are land-dwelling beings, more rapid warming on land means even more impact on everything from human health to growing food.

"All the things most people really care about — food, wildlife, sports, spring allergies, forest fires, their personal comfort — are being affected by human-caused warming much faster than the gradual warming of the globe would imply," warns Francis.