Climate change and overfishing are increasing toxic mercury levels in fish, study says

Mercury levels in the seafood supply are on the rise, and climate change and overfishing are partially to blame, according to a new study. Scientists said mercury levels in the oceans have fallen since the late 1990s, but levels in popular fish such as tuna, salmon and swordfish are on the rise.

According to a new study by Harvard University researchers in the journal Nature, some fish are adapting to overfishing of small herring and sardines by changing their diets to consume species with higher mercury levels.

Based on 30 years of data, methylmercury concentrations in Atlantic cod increased by up to 23% between the 1970s and the 2000s. It links the increase to a diet change necessitated by overfishing.

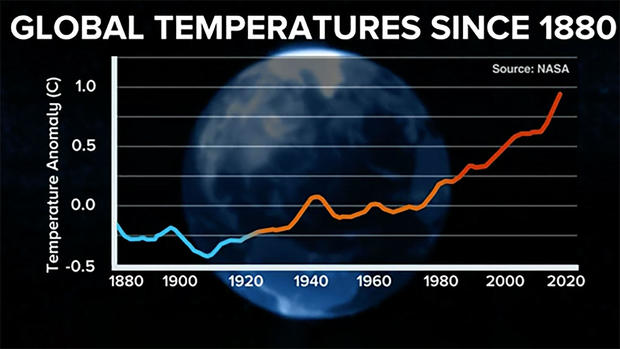

But overfishing isn't the only contributor to higher mercury levels in fish. Climate change — and the rising ocean temperatures that come with it — means fish are more active and need more food to survive. Consuming more prey means consuming more mercury.

The study also found that mercury levels in Atlantic bluefin tuna have increased by an estimated 56% due to seawater temperature rise since 1969.

Climate change "is not just about what the weather is like in 10 years," said lead researcher Amina Schartup. "It's also about what's on your plate in the next five."

Scientists said human exposure to methylmercury — the compound created when mercury enters the ocean — is especially risky for pregnant women, as it has been linked to long-term neurological disorders when fetuses are exposed in the womb. It is considered a major public health concern by the World Health Organization.

"It's not that everyone should be terrified after reading our paper and stop eating seafood, which is a very healthy, nutritious food," senior author Elsie Sunderland told Reuters. "We wanted to show people that climate change can have a direct impact on what you're eating today, that these things can affect your health ... not just things like severe weather and flooding and sea level rise."

Since the late 1990s, mercury concentrations have declined overall following increased regulations and decreased coal-burning power plants. In 2017, a global treaty was introduced to reduce mercury emissions.

But mercury levels in fish have not fallen as expected. The treaty failed to account for overfishing's massive effects on marine ecosystems or climate change's impact on the diets of fish. So, much of our current seafood supply actually contains more mercury than before.

According to a recent report by Australian climate experts, the world's oceans will likely lose about one-sixth of its fish and other marine life by the end of the century if climate change continues on its current path. If the world's greenhouse gas emissions stay at the present rate, that means a 17% loss of biomass — the total weight of all marine animal life — by the year 2100. But if the world reduces carbon pollution, losses can be limited to only about 5%, the study said.

But our regulations against mercury pollution could be weakening under the Trump administration. In December, the Environmental Protection Agency targeted an Obama-era regulation credited with helping dramatically reduce toxic mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants.

In the U.S. coal power plants are the largest single manmade source of mercury pollutants. As coal combustion emits mercury into the atmosphere, the ocean absorbs it, converting it into methylmercury. The EPA proposal argued that savings for companies were greater than any increased perils to safety or the environment.

The carbon we release into the atmosphere has a direct correlation to the toxins that end up in our food supply.

Methylmercury levels increase when an animal eats its prey — accumulating in larger doses as it goes through the food chain. So when a human consumes tuna, for example, it is also consuming all of the mercury consumed by its prey, all the way down the food chain.

According to the study, about 80% of exposure to Methylmercury in the U.S. comes from seafood, and 40% from tuna alone. Scientists said stronger regulations are needed for greenhouse gases and mercury emissions in order to keep our fish supply healthy and thriving.