Classified: Keeping close the nation's secrets

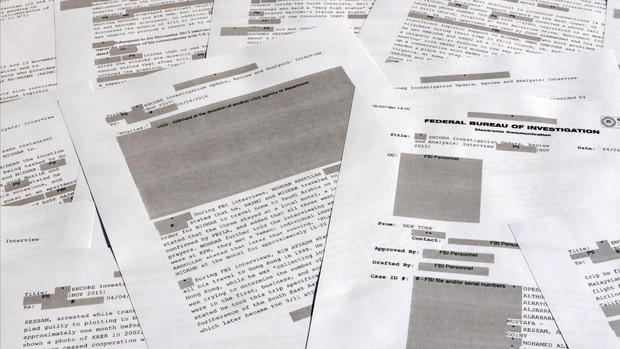

The documents spread out on the carpet at Mar-a-Lago, their classification markings clearly visible, are tiny drops in a tsunami of secrets kept by the U.S. government.

CBS News national security correspondent David Martin asked John Fitzpatrick, who managed the flow of classified documents in both the Obama and Trump White Houses, "Do you have any estimate of how many classified documents there are?"

"That's really unknowable," he replied.

Fitzpatrick said the last reliable count was taken when most classified documents existed only on paper. "They were in the tens of millions of documents a year," he said.

"Has it become easier or harder to classify information?" asked Martin.

"As a practical matter, it has become easier. The proliferation of classified computer networks provides an environment where the proliferation of classified material increases."

The 9/11 attacks and all the subsequent alarms of terrorist plots against the homeland brought with them a surge of classification, which even worries the person in charge of keeping secrets, national intelligence director Avril Haines, who testified to Congress that overclassification is a national security problem. Earlier this year, she wrote, "Deficiencies in the current classification system undermine our national security," by making it difficult to share information with allies and the public."

"It's a fairly arresting statement," said Martin. "The system designed to keep national security secrets is undermining national security?"

"I agree with her," said Fitzpatrick. "There's a culture of classification: Protecting secrets is always better than releasing secrets. It's a false binary, but it's the way people do it."

Tom Blanton, director of the National Security Archive, said, "Most secrecy is not about real damage. It's about preventing one form of embarrassment or another by the government."

For the past 35 years, the National Security Archive has used the Freedom of Information Act to pry loose boxes upon boxes of previously-classified document. "We've seen probably on the order of 10 to 20 million pages of declassified U.S. government documents over the years," Blanton said.

The walls are lined with some of his favorites. He showed one to Martin: "It's a piece of internal CIA email about the torture program, and specifically about how they destroyed the videotapes of the water boarding."

If tapes of the CIA's waterboarding of captured al Qaida operative Abu Zubaidah ever became public, the memo said, "they would make us look terrible; it would be 'devastating' for us."

Blanton said, "This document would have stayed classified indefinitely under the CIA's sources and methods protection."

"Do you file Freedom of Information Acts requests on a daily basis?"

"About 1,500 a year."

"How many people are there out there who can classify documents?"

"Almost 5 million."

Today's classification system grew out of the secret project to build the atom bomb, arguably the greatest secret ever. The head of the project, Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves, later wrote he was keeping it secret from "the Germans," "the Japanese," "the Russians," "all other nations," and "those who would interfere," which included Congress.

"What General Groves created in the national security classification system was a big bang, and that universe is still expanding," said Blanton.

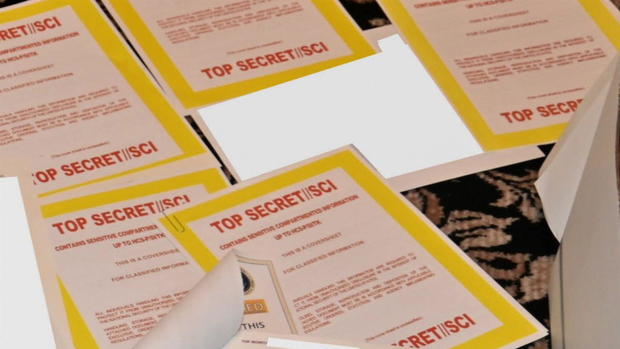

The three basic levels of classification are confidential, secret and top secret. Confidential information would cause "damage" to the national security if it got out; secret would cause "serious damage"; and top secret "exceptionally grave damage."

Beyond top secret there is SCI (which stands for sensitive compartmented information, also known as special access programs). "Those are considered the most closely held secrets of the government," Fitzpatrick said.

"Do you have any idea how many Special Access Programs there are?" asked Martin.

"Ultimately, you're talking about hundreds," he replied.

Each special access program has its own code name. Here's a once-top secret memo directing that "satellite photographs must be handled in a separate compartment known as TALENT-KEYHOLE." A document like this would be kept in a room called a SCIF, or sensitive compartmented information facility. "There are physical standards for locking them, for alarming them, and soundproofing them," Fitzpatrick said.

The best known SCIF is the White House Situation Room, where the president meets with his national security advisors. All the presidential libraries are equipped with SCIFs, but there is no SCIF at Mar-a-Largo.

Martin asked, "Does the President of the United States have a security clearance?"

"The answer is no," said Fitzpatrick. "The president derives his authority to see any classified information from his constitutional authorities."

"Is it assumed that the president has a need to know absolutely everything?"

"It is."

"Can the President just flat out order a document to be declassified?"

"Yes. The president's authority to classify or declassify information is derived from his own constitutional authority."

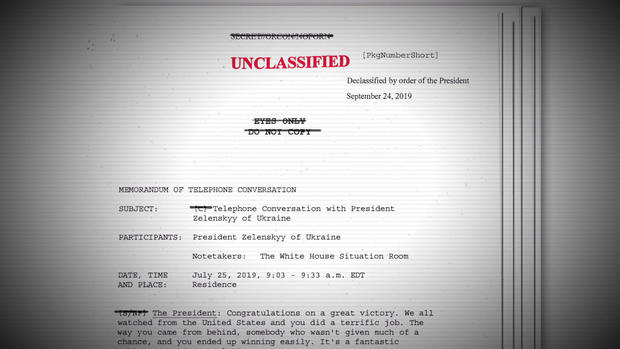

When he was president, Donald Trump declassified the transcript of his phone call with Ukraine's President Zelensky asking for help in digging up dirt on Hunter Biden. All of its original classification markings have been crossed out and it is clearly stamped "unclassified."

Compare that with the documents the FBI spread out on the floor after their search of Mar-a-Largo.

"There's not a line through those markings," said Blanton. "There's not a stamp saying, 'This was released on X-date, authority of somebody.' Even when the president says, 'I want something declassified,' there's a whole process it has to go through."

- The National Archives confirms it found classified materials at Mar-a-Lago

- Washington Post: FBI searched Trump's Mar-a-Lago for classified nuclear documents

- Mar-a-Lago search inventory shows documents marked as classified mixed with clothes, gifts, and press clippings

- Timeline: The government's efforts to get sensitive documents back from Trump's Mar-a-Lago

- Trump claims presidents can declassify documents "even by thinking about it"

Most documents are not declassified until long after they have been shipped to a presidential library, like the Lyndon B. Johnson Library in Austin, Texas, where all the papers of his administration are stored – and where, more than half a century later, some still remain classified.

Blanton recently asked the George W. Bush Library to declassify the notes of the president's prep sessions for his first meeting with Vladimir Putin in 2001: "Great moment in history. You know, this is 22 years ago, when Putin was still our friend. Might even do us some good today in figuring out Putin's grievances, and maybe some off-ramps out of this current tragedy in Ukraine that Putin started."

The National Security Archive filed its FOIA request in January of this year. "Nice people down at the George W. Bush Library in Dallas said, 'Sorry to tell you, Mr. Blanton, but it's going to be 12 years before they get around to it.'"

Martin asked, "Which side is winning? The forces of classification, or the forces of declassification?"

"Oh, the forces of classification have long won!" Blanton replied.

For more info:

- Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines

- National Security Archive

- Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room (cia.gov)

Story produced by Mary Walsh. Editor: Lauren Barnello.

See also: