Citigroup admits its predecessors likely benefited from slavery

Citigroup has grown into the nation's third-largest financial institution in part because its predecessors in the 1800s indirectly profited from slavery, the company acknowledged in a blog post this week.

The admission came as the Wall Street firm, JPMorgan Chase and other big banks have re-examined their roots in years, looking to unearth what roles they may have played in creating today's racial inequities.

Citi first explored its historic ties to slavery 20 years ago but "did not find records providing evidence of any direct involvement," Edward Skyler, Citigroup's head of public affairs, wrote in the post. But a second initiative conducted last year found that the bank's predecessors "likely profited from financial transactions and relationships with individuals and entities ... involved in or connected to the U.S. slave trade," according to Citi's research summary, which Skyler linked to in his post.

One such predecessor was Moses Taylor, who served as director and president of City Bank of New York — Citi's name at the time — for much of the mid 1800s. Taylor amassed a large fortune from Cuba's sugar plantations, which used slave labor, according to Citi's research.

Many of the nation's biggest banks, including Citi, are conglomerations of financial institutions that have merged or bought each other over the years. Citi traces its founding back to 1812 as City Bank of New York. What today is known as Citigroup grew from more than 400 predecessor companies, of which 21 were created before 1866. Slavery as a legal institution in the continental U.S. formally ended on June 14, 1866.

Citi conducted its most recent review of the company's legacy using archives from Cornell University, a historic society in Mobile, Alabama, the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress and the Alabama Supreme Court.

- Florida's new Black history curriculum says "slaves developed skills" that could be used for "personal benefit"

- Wells Fargo to rethink diversity policy after former employees speak of fake interviews

- Report links history of slavery to racial inequalities in Philadelphia's criminal justice system

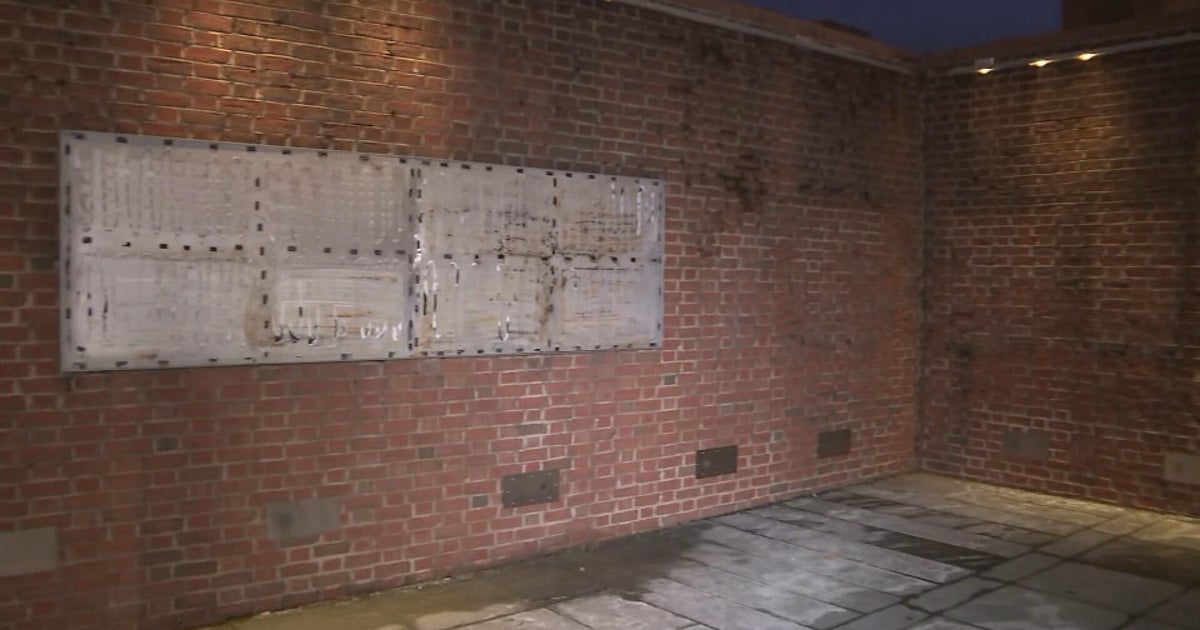

The review also found that Farmers' Loan and Trust Company, which later became Citibank (a part of Citigroup), accepted a trust application in the amount of $600,000 for property owned by Henry Hitchcock, Alabama's first attorney general, a man who enslaved 24 unknown people.

The property, valued at $1.9 million at the time, raised concern among Citi's researchers team that the assets held under trust by Farmer's Loan "may have included persons enslaved by Hitchcock." While they ultimately concluded that the trust transaction did not result in Citi's predecessor "owning" any people enslaved on the property, it did acknowledge the bank's financial benefit from its dealings with Hitchcock.

"Although the focus of our historic records review was Citi's own activity, we acknowledge that people who played important roles in Citi's history had ties to the slave trade," Skyler wrote. "Additionally, other founding or early directors of City Bank of New York likely owned enslaved persons. None of this changes the past but it can help make for a more equitable future."

Citi also found that the company held bank accounts for individuals and companies that operated in slaveholding states.

The bank is hardly alone in its connection to U.S. slavery. JPMorgan in 2005 acknowledged that two of its predecessor banks had links to the slave trade, with two banks in Louisiana receiving thousands of slaves that were used as collateral.

Wachovia, the Charlotte, North Carolina-based bank that failed in the 2008 financial crisis and was subsequently bought by Wells Fargo, also admitted in 2005 that its history has ties to slavery. Wachovia found that its predecessors — the Bank of Charleston and Georgia Railroad and Banking Company — both owned slaves.

—The Associated Press contributed to this report.