Chinese researcher claims to have genetically altered babies using CRISPR

A Chinese researcher has created an international controversy over science and ethics, after claiming he helped make the world's first genetically-edited babies. According to The Associated Press, the doctor, He Jiankui of Shenzhen, who trained in the United States, altered embryos for seven couples undergoing IVF, with one pregnancy resulting in the birth of twin girls.

This kind of gene editing is banned in the United States. The changes can be passed to future generations and could harm other genes.

His claims have not been independently verified. They also were not published in a medical journal, where they could be vetted by experts.

On Monday Dr. David Agus, who is an oncologist and leads the USC Westside Cancer Center, explained the doctor's procedure on "CBS This Morning."

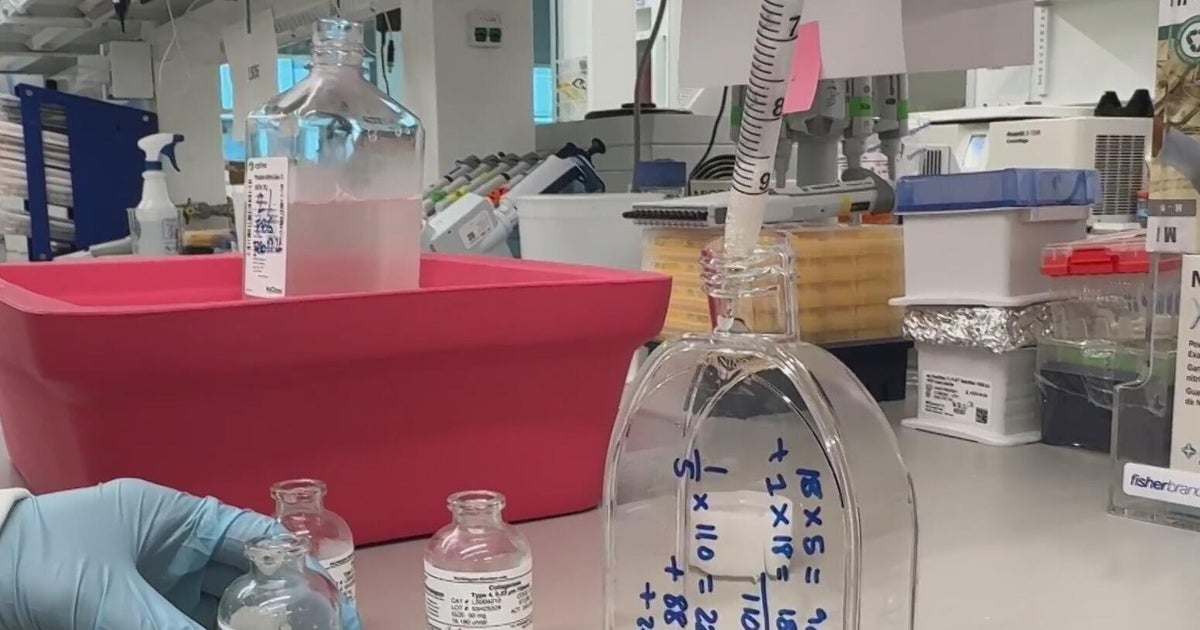

After creating an embryo via in vitro fertilization, the doctor used the gene-editing tool CRISPR (short for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) to surgically change one out of 3 billion letters of the embryo's DNA code, in order to build in a resistance to HIV infection. "He changed the code for the HIV receptor, for the AIDS receptor, into the cell and then that embryo was put into a woman," Agus said.

The process is being promoted as a means to eliminate the threat of HIV (the father of the children has HIV, though the mother does not). Agus said that such gene editing may potentially eliminate HIV. "But in these twins only one had it fully taken out; the other one had it partially taken out. But at the same time, it raises the risk of death by flu, and it increases the rate of getting West Nile virus, so it's not a perfect treatment.

"And the problem is, there's a lot of off-target effects. This enzyme is promiscuous. Even though it could change one letter, it happens to maybe change other things in the DNA."

Agus said that when gene editing is used with adults, genetic changes aren't passed down, unlike when the DNA of a child is altered.

He called the procedure an experiment on children, and that while the parents gave consent, Dr. Agus noted, "On the consent it said 'HIV vaccine,' it didn't say 'gene editing experiment.' This is something [that] can get rid of in-born errors of genetic disease potentially, but a lot more science needs to be done. It's way too premature to put it in kids, because we're not going to know the answer for 10, 20, 30 years whether it works."

Dr. Kiran Musunuru, a University of Pennsylvania gene editing expert and genetics journal editor, told the AP that He's experiment on human beings "is not morally or ethically defensible," and called it "unconscionable."