China plans a clampdown that could end Hong Kong's dreams of democracy

At the opening of China's once-a-year National People's Congress on Friday, the country's leaders revealed the Communist Party's top two concerns for 2020 and beyond: national security headaches from Hong Kong's defiant pro-democracy movement, and economic growth in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Beijing's 3,000-member rubber-stamp legislature is poised to usher in controversial "national security" legislation that would ban treason, secession, sedition and subversion in the former British colony.

There's mounting fear that Beijing would use the new laws to subvert semi-autonomous Hong Kong's remaining rights, which include freedom of speech and assembly, and the city's independent judiciary. If that happens, it would be a death knell for the "One Country, Two Systems" policy that officially guarantees Hong Kong's semi-autonomy until 2047.

"We will establish sound legal systems and enforcement mechanisms for safeguarding national security," Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, the country's number-two leader behind President Xi Jinping, said at the opening of the People's Congress. He added that Beijing would support Hong Kong in growing its economy, improving living standards and better integrating its development into China's overall development.

Hong Kong "is an inalienable part of the People's Republic of China," said Hong Kong's Beijing-backed Chief Executive Carrie Lam in a written statement late Friday, adding that her administration supports the National People's Congress deliberation.

Late Thursday, as the first reports emerged of Beijing's intent, National People's Congress spokesman Zhang Yesui said the push to enact national security legislation from Beijing was required given the "new situation and demands" in Hong Kong. He said action at the national level was "entirely necessary."

The "new situation"

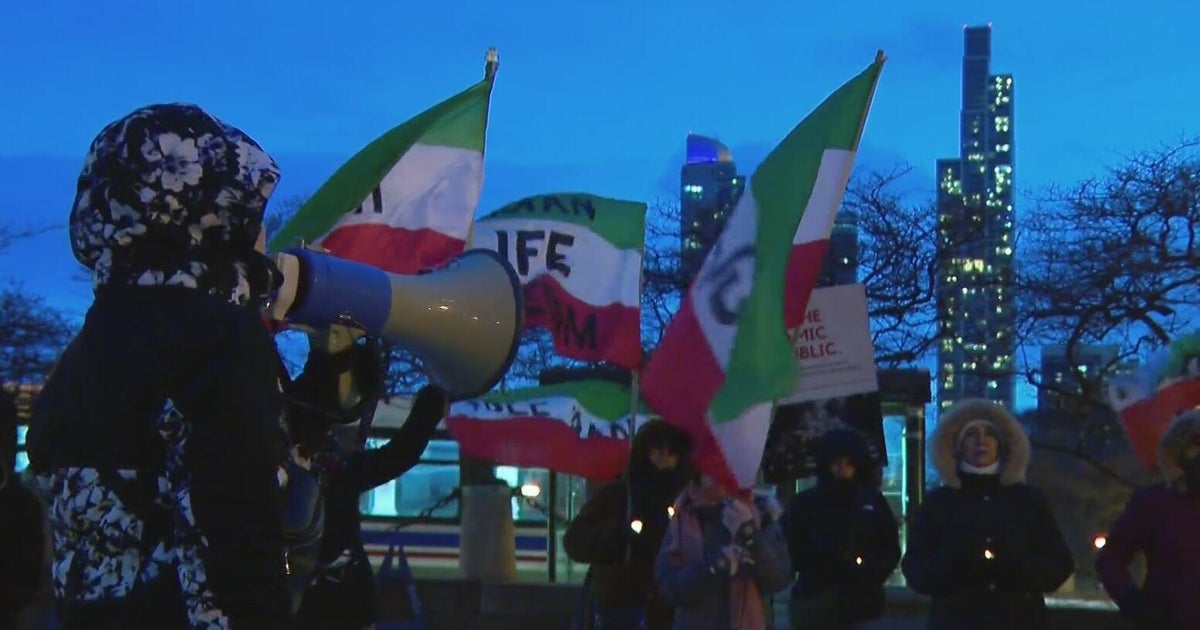

From June to December of 2019, Hong Kong was roiled by record-turnout, peaceful protests that devolved into countless smaller, violent street demonstrations. The unrest was sparked by a despised extradition bill in Hong Kong's legislature, but it morphed into wider demands for universal suffrage, and then into a wholesale rejection of Beijing's power over the semi-autonomous region.

One of the most popular protest slogans of last year was: "Liberate Hong Kong, this is the revolution of our times."

In local district council elections last November, pro-democracy candidates won landslide victories against pro-Beijing politicians, which was seen as a clear referendum on Hong Kong's pro-China administration, and by extension the Communist Party itself.

The broad popular support for the pro-democracy movement has made President Xi Jinping, widely considered China's strongest leader in decades, keen to bring the southern region to heel.

Hong Kong's Civil Human Rights Front, the group that organized many of the city's major protests last year, said it couldn't confirm details of any upcoming demonstrations, noting in a statement posted Friday to Facebook that it was "currently extremely difficult to initiate any action."

Nonetheless, the group called on Hong Kong's citizens to "stand up not only for your job, but for human rights, democracy and the freedom of the rule of law regardless of your political stance. We need each and every one of you to help save Hong Kong."

Warnings from the U.S.

"Any effort to impose national security legislation that does not reflect the will of the people of Hong Kong would be highly destabilizing," said U.S. State Department spokeswoman Morgan Ortagus. She added that such a move by Beijing, "would be met with strong condemnation from the United States and the international community."

Earlier this week, President Donald Trump said Washington would react "very strongly" if Beijing moved to crack down on Hong Kong. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said the White House could reconsider Hong Kong's special trade status, which excludes the city from trade restrictions placed on mainland China.

Washington wielded the same threat during last year's protests: If the State Department concluded that Hong Kong was no longer "sufficiently autonomous," then the status — which hugely benefits the central Chinese government — could be revoked.

The U.K. Foreign Office weighed in more tepidly, saying: "We expect China to respect Hong Kong's rights and high degree of autonomy." Great Britain handed Hong Kong back to China in 1997 after 99 years of colonial rule.

On May 28, the closing day of this year's shortened (thanks to the pandemic) National People's Congress, the new national security legislation is scheduled to be voted on. It's all but assured to pass, as the Congress is effectively a rubber-stamp machine for the will of the ruling Communist Party, and the law could be implemented as soon as August.