How China developed its first large domestic airliner to take on Boeing and Airbus

As China moves closer to mass production of its first large passenger jet, details are emerging that reveal how a state-owned aircraft manufacturer was able to build a plane that looks remarkably similar to a Boeing 737.

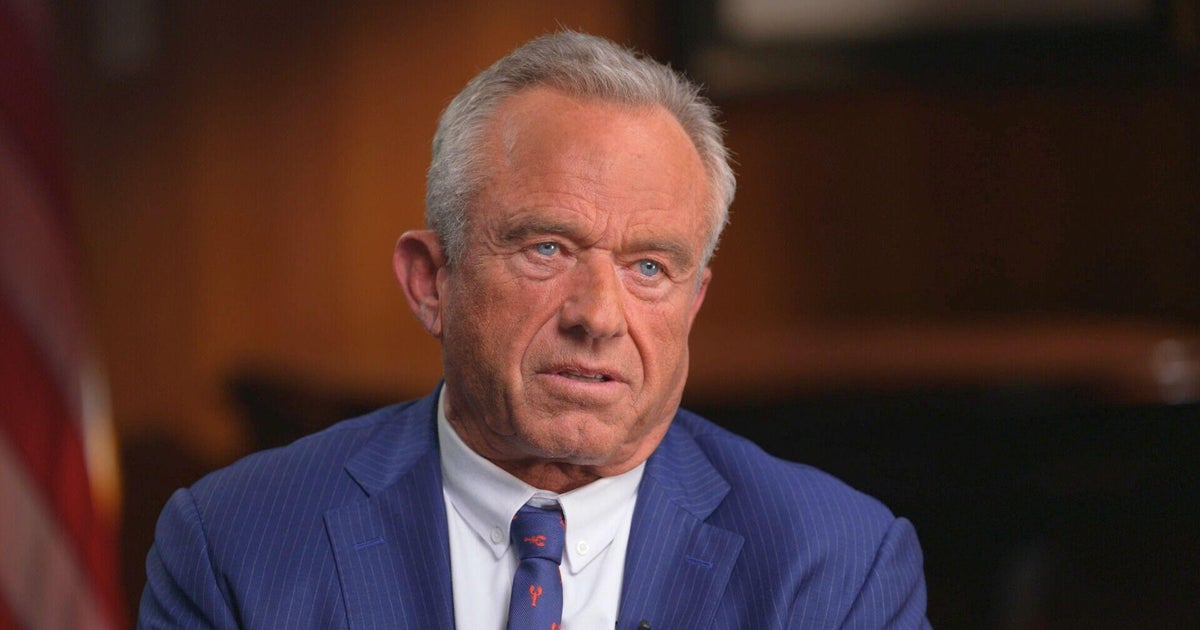

"It really looks like a knockoff," said Matt Pottinger, former deputy national security adviser during the Trump administration, describing the Chinese-built C919.

Together, the duopoly that is Airbus and Boeing have dominated the skies for decades, cornering the plane manufacturing market globally. While these Western-based companies have maintained their hold on the industry, China — which has never been able to manufacture anything like a 737 — is seeking to change that. And to do so, U.S. national security experts point to a combination of economic pressure and espionage.

Critics argue that China's C919, the aircraft made by state-owned company, COMAC, is not only a threat to the U.S. economy and an effort to elbow Boeing out of the huge market in China, but also a chance for the Chinese military to benefit from access to American-made technology.

The C919 is so important to the Chinese Communist Party it's been called a source of national pride. The development of a low-cost large domestic airliner has been a top strategic goal for over a decade, as it could position China to eventually dominate one of the world's largest markets for jets. That possibility could end up costing the U.S. economy up to $1.5 trillion over the next 20 years.

Jon Ostrower, editor of The Air Current, a news site that covers the aviation industry, told CBS News that "aerospace is part of the game of nations" and that China has been working towards mastery of the field and eliminating competition.

"It ultimately represents self-reliance, modernity, the desire to engage with the world," Ostrower said. He adds, over the next 20 years, "you're talking about a market [in China] of about 8,000 airplanes and if China wants a chunk of that, that fundamentally means fewer airplanes for Boeing and Airbus to deliver."

In 2015, China unveiled the C919 prototype to much fanfare, literally rolling out the red carpet. However, after lengthy delays, the first completed C919 was finally delivered to China Eastern Airlines four months ago.

The C919 looks similar to its competition, the Airbus A-320 and the Boeing 737. The familiar look is by design, according to current and former national security officials like Pottinger.

"China has a lot of different varieties of ways of relieving people of their intellectual property," Pottinger said.

Sixty percent of the plane's components are the result of deals with America's top aerospace companies like Collins Aerospace, GE Aviation and Honeywell. Entering into these joint ventures with China's industry is the steep price paid by American companies for admission into the nation's massive market.

"If you want to sell stuff to 1.3 billion people in China, you're gonna have to give us the blueprints for your goods or you're gonna have to go into a joint venture with us, where you're going to train our engineers," is how Pottinger explained China's strategy. "This is what we call 'forced technology transfer.'"

National security experts say there's another means by which China works to acquire American innovation: espionage.

Bill Evanina, who was America's top counterintelligence official when, beginning in 2017, the Department of Justice exposed an intricate scheme targeting American aviation technology, says the C919 is "proof" of the Chinese government's espionage, adding "they've been very successful at it."

A 2019 report by the cybersecurity firm Crowdstrike revealed one major focus of Beijing's spycraft: components of the C919.

"A major focus of this strategy centered on building an indigenous Chinese-built commercial aircraft designed to compete with the duopoly of western aerospace," the report states. "That aircraft would become the C919 — an aircraft roughly half the cost of its competitors, and which completed its first maiden flight in 2017 after years of delays due to design flaws."

Evidence gathered by the U.S. investigators and shared with CBS News shows a Chinese intelligence officer, Xu Yanjun, "used aliases, front companies, and false documents" as well as an intense hacking effort to obtain corporate secrets. Xu targeted a GE aviation engineer who specialized in jet engine design.

Xu's outreach to the engineer caught the attention of the FBI, which orchestrated a sting operation, directing the GE employee and listening to his communications as they planned to meet in person.

Speaking in Chinese, Xu asked the GE engineer to bring his company laptop and "carry the stuff along," so Xu could "look over the stuff." The employee assured him, "I certainly will have the computer."

Two months later, Xu traveled to Belgium to meet the employee, but the FBI was waiting. He was brought to the U.S. to stand trial and late last year, sentenced to 20 years for spying.

A spokesperson for China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs referred to the charges against Xu in 2018 as "something made out of thin air." Evanina called the prosecution "monumental."

"It's the first time ever where we arrested, indicted, convicted in a jury, and sentenced a known intelligence officer running a cell, collecting aviation technology to benefit the civilian and military apparatus of the Communist Party of China," Evanina said.

GE officials told CBS News that the espionage effort targeting their engine design was detected early, and the company fully cooperated with the federal investigation that followed.

"Intellectual property is among our most valued assets, and the impact to GE Aerospace was minimal thanks to early detection, our advanced security systems, and our cooperation with the FBI," the company said in a statement.

The sentencing memorandum submitted by prosecutors in Xu's case revealed two state-owned companies involved in building the C919 were "the intended recipients of his spycraft."

"Do you remember Alcatel, Marconi, Nortel?" Pottinger asked, referring to the Western companies that once manufactured telecommunications products. "Those companies don't exist anymore. They're dead. And Airbus and Boeing are on the kill list now."