Cyber thieves target new victims with more sophisticated card-skimming devices

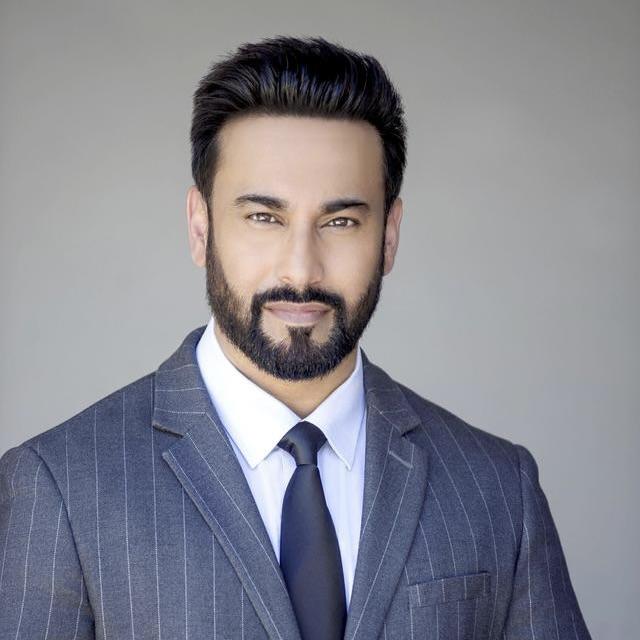

Michael Perez never planned on becoming a cybercriminal.

In the 1980's, as personal computers were just starting to appear in homes across the country, Perez was a young boy who found tinkering with technology much more entertaining than toys. By the time he was 12 years old, he was building his own computers.

"My uncle would bring the parts, buy them and [I'd] start building it," said the Miami native. "I've always loved computers. I've been fascinated by programming, but I never had the time to actually dedicate to educate myself on it or learn it."

But growing up in a poor, mostly Hispanic neighborhood, Perez says he found little financial opportunity outside of the occasional electronics or cell phone repair job.

"I would micro solder stuff and fix the components on the boards. And I got to a point where I started doing these things, but I wasn't being profitable at the time," said Perez.

The "mechanic" shares his secrets

That's when he said a friend from the neighborhood introduced him to the idea of building card skimmers and installing them at gas stations across the country to make money.

"I sort of put it together and like in two days I had a working skimmer."

Law enforcement in South Florida calls these criminals "mechanics."

Perez says he used Google Streetview to find the easiest gas pumps to target.

"I'll zoom in to see where, what the face looks like, what the door looks like, what the gas pump model is," he said. "I would open access to the gas station pump with a universal key, open it up. And inside I would take out a reader and then put in my modified reader."

Perez said each of his skimming devices could collect anywhere from 750 to 1,000 card numbers for storage. He would then pull up to the pump and extract the information via Bluetooth. In three days of skimming, he could steal up to $30,000.

According to the FBI, skimming costs financial institutions and U.S. consumers more than a billion dollars each year.

Rise in skimming

Data analytics company FICO monitors more than 2 billion financial transactions a month, looking for unusual spending behavior, things that are out of the ordinary like skimming. According to data it collected, the number of compromised cards jumped 368% last year compared to the year before.

"I think that we're seeing a burst of skimming activity coming out of the pandemic," said T.J. Horan, vice president of product management at FICO. "During the pandemic there was a lot less point-of-sale transactions. Many of us were staying at home and not doing the normal kinds of things that we do. And so, we've suddenly seen a big increase. The other thing is fraudsters always are looking for weak links and looking for opportunities."

And that has been a challenge. Even with new advances in security and technology, experts say fraudsters have done a good job of staying one step ahead of law enforcement and banks.

"They're constantly evolving. Law enforcement is constantly trying to find ways to keep up," said Charles Leopard, assistant special agent at the U.S. Secret Service's Miami field office, home to the agency's largest cyber forensic lab in the country.

Inside the massive lab, technicians work on investigations that impact the economic infrastructure of the United States — everything from counterfeit currency to email phishing scams to any type of mortgage or loan fraud. In addition to that, they also investigate access device fraud, like credit card fraud and skimming.

"This lab in particular is very beneficial to the municipalities and state and local agencies around here as this lab takes in tons of violent crime, homicides and any other type of electronic device that needs to be examined, that is seized or part of a federal, state or local crime," said Leopard.

Each year, the 50 full-time and 75 part-time computer forensic technicians conduct about 5,000 examinations — processing more than a petabyte of data volume. But even with those resources and computing power, Leopard says scammers are constantly using new ways to thwart the latest security measures.

Skimmers evolve

Leopard says that in the 25 years skimming has been around, the devices have advanced from the handheld card readers used in the late 1990s by restaurant wait staff to ATM overlays and point of service panels that slip right on top of the card readers. In recent years they began finding tiny hidden cameras right on the card readers.

"There's a small pinhole on this piece of plastic that would normally sit just like this on the ATM machine and would capture the keypad. So, they would use one of these overlay skimmers and then they would insert a camera so they would get the pin."

"It's just evolved in how the criminals are capturing the information," he said.

They've even moved to what he calls deep insertion skimmers, devices so thin they can slip right into the reader undetected — making it a challenge for even a professional technician to remove and tougher for law enforcement to keep up.

"Law enforcement and its partners will put a stop to some of the vulnerabilities that we see in ATMs or point of sale terminals and merchants," said Leopard. "And then a couple of months, everything would be quiet. And then the cyber criminals will find a way around it. And then there'll be a new spike until we get it stopped. So, it's constantly the cat and mouse game to find ways to prevent it."

New victims

Since mid-2022, skimming thieves have been training their sights on an especially vulnerable group — the food insecure.

In recent months, thousands of Americans who rely on Federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance, or SNAP, have had their funds stolen from their accounts.

"You get a set amount of money every month from the government to help pay for your groceries," said Sung Hee Lee, a Boston college student who says she works 30 hours a week, attends school full-time and struggles to make ends meet.

Each month, she goes to the grocery store to stock up on food, but on a recent trip, just a day after her electronic benefit (EBT) card was reloaded, she discovered her account balance had almost entirely vanished. Only 40 cents remained.

"I learned that from customer service on the phone when I was at the grocery store trying to handle all this. All my money was used a few days prior, right after my money just came in," said Lee.

Lee found that someone had used her card number to make purchases nearly a thousand miles away at a Sam's Club store in Illinois.

Lee has never shopped at a Sam's Club.

"I can't afford a Sam's Club membership," she said.

"The card has always been in my possession and I've never given out my information," she said. "So, the only way this could have happened is someone stealing it directly, either while I used it at some sort of random convenience store, and my information might have gotten sold and skimmed."

The cost of fraud

The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees the federal SNAP program, told CBS News via email that prior to this year, there was no federal requirement for states to track reports of benefit theft via card skimming, card cloning or other similar fraudulent means.

We contacted all 50 state agencies that administer SNAP programs and only a few could tell us how much money has been stolen – but it's clear it's in the millions.

In Massachusetts, between June of 2022 and March of 2023, $2.9 million was stolen, impacting more than 6,700 households. In New York, between January of 2022 and March of 2023, $7 million was stolen, with more than 10,000 complaints of skimming. And in California, $7 million was stolen between July of 2021 and November of 2022.

A security weakness

EBT cards are different than your average debit or credit card. They lack the enhanced security of an integrated EMV chip, which most banks incorporated in 2015. Instead, they rely solely on 1970s-era technology: a magnetic stripe.

"It doesn't make any sense that the SNAP program, which spends $157 billion annually, is using a glorified hotel room key to provide benefits to the food insecure," said Haywood Talcove, CEO of LexisNexis Risk Solutions Government Business.

Talcove's company gathers data for government agencies to help prevent fraud, waste and abuse in public programs.

A recent LexisNexis study found that every $1 of benefits lost through fraud ultimately costs SNAP agencies $3.72 in additional costs related to detection, investigation, reporting and administrative tasks. These costs are ultimately passed on to taxpayers, who fund the SNAP program.

The study also found that attacks on SNAP were primarily due to identity fraud, eligibility, account takeover, and trafficking. It's ultimately a loss passed on to every taxpayer.

"What you have is an antiquated system. You have antiquated technologies, you have the USDA with very [few] enforcement tools, and criminal groups learned a lot from what happened during the COVID pandemic and how to steal government benefits," said Talcove.

Talcove says criminal enterprises have been selling stolen card information on the dark web to the highest bidder – in some cases, he says, dangerous international crime syndicates.

"The lack of controls that USDA has in place make it so easy for these organized groups, particularly domestic and transnational countries like Romania, Nigeria, Russia and China, to put phishing and skimming devices and steal people's valuable benefits that they use to feed their families," he said.

"What the USDA needs to do today is get off those glorified hotel room keys, get those chip-enabled cards put in place. They have to start doing front-end identity verification."

Enhanced security

Data shows chip technology does make payment cards more secure than the magnetic strips used on SNAP cards.

According to VISA, stores that started accepting chip cards back in 2015 saw a 76% drop in fraud over the next three years.

"Because the magnetic swipe is not encoded, it's not encrypted, it's wide open. So, you can use any reader to pull that information," said Leonard.

Last October, with complaints from constituents growing in her home state of New York, U.S. Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and a dozen other New York lawmakers wrote to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. They urged him to allow states to reimburse skimming victims and look at better security technologies for EBT cards.

"Making sure that we fix this problem was a high priority for me," said Gillibrand. "For a lot of families without that supplemental nutrition assistance, they don't have enough to feed their families, to feed their children, to have enough food at the end of the month."

Included in the passage of the omnibus bill by Congress was a framework of Senator Gillibrand's SNAP Theft Protection Act, which directs federal funds to states to reimburse SNAP recipients who've been skimmed. It also, for the first time, calls for states to track SNAP fraud data and investigate beefing up security for EBT cards.

But the legislation stopped short of requiring the USDA to switch to more secure technologies like chips.

Over the course of two months, CBS News submitted multiple interview requests to the USDA to discuss the SNAP fraud and skimming issue, but they failed to provide a representative.

Sung Hee Lee says she had trouble getting in touch with USDA as well.

"Even if you press all the different menu options, no one would take you to a representative. And even if you try to write an email I never heard back," she said. She eventually gave up on ever getting her stolen SNAP benefits reimbursed.

The agency has announced it is launching a pilot program to test the more secure contactless and mobile payments for SNAP recipients in five states: Illinois, Missouri, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Massachusetts.

"I think tap-to-pay as well as paying via your phone is a very safe way to do it," said Leonard. "Some have already found ways to compromise the contactless payments. But it's not to the degree that we're seeing with skimmers."

That pilot program won't start until next year, at the earliest.

Redemption for a "mechanic"

As for Michael Perez, his days of skimming eventually caught up with him.

"I got arrested on November 27, 2017, and they took me to the county jail. It was a joint operation with Secret Service and Miami-Dade," he said.

Perez spent more than two years in federal prison. But the guilt of his crime he says crept up on him during a hurricane in Texas.

"I remember going to the hotel and everybody was out of their houses, checking into hotels because they didn't have any homes," he said. "Everything was destroyed. And I was there doing that damage to them. And I remember the person in front of me, their card got declined and she didn't have a way to stay at the hotel at that moment. That's when it hit me. It broke my heart right there."

Perez has traded in his moniker of "mechanic" for counter-skimming consultant. He's now working with security firm Unchained Leadership & Consulting to help law enforcement try to stay one step ahead of fraudsters.

"I've made software for them, and I've made devices and I've come up with technology to help prevent or to catch on to fraud," he said. "I want to keep doing that. I'm doing what I love, and it feels good."