Los Angeles Zoo uses new tactic to boost California condor population

The California condor breeding program at the Los Angeles Zoo helped saved the species after it was on the brink of extinction in the early 1980s. Now, the zoo has discovered a new technique to keep the population of the largest bird in North America growing.

In 1982, there were only 22 condors, which have a wingspan of 9.5 feet, in the wild, according to Steve Kirkland, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. By 1984, the breeding population was down to nine, he said.

Scientists captured all the surviving condors and the breeding program at the Los Angeles Zoo was formed, CBS Los Angeles reporter Joy Benedict reports. This year, the 1,000th condor reared his head inside a rocky hillside at Zion National Park.

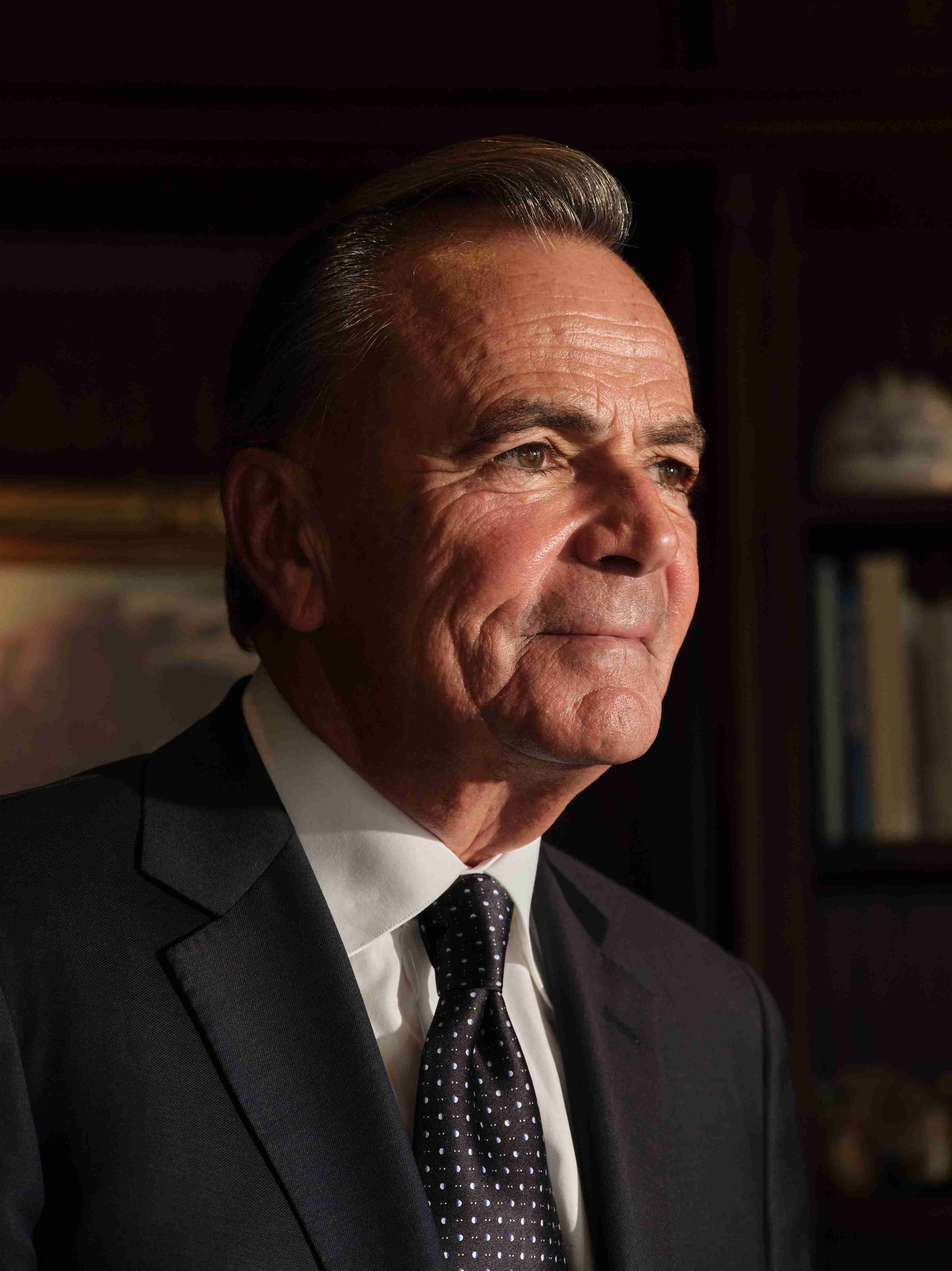

"This is a California native bird. This belongs right in our backyard," said Mike Clark, the condor keeper at the zoo.

In the wild, condors might raise one chick every two years, but at the zoo, when a condor lays an egg, keepers take it, prompting the bird to lay another. Then, Clark tried something never done before. He wanted to know if a parent would foster more than one chick, so he approached a bird who knew him well.

"Here is a sexually mature bird that has been breeding for years and years and years, raised tons of chicks with another bird. She sorta kinda got attached to me because I was the only one she was interacting with," Clark said.

"So she fell in love with you," Benedict said.

"Yes, and I her," Clark said.

The technique was a success, and this year, for the first time ever, the chicks are all being raised in pairs.

The zoo spends more than half a million dollars a year trying to save the species, but the only condor zoo visitors may see is Dolly, who arrived with a damaged wing they couldn't repair.

"So you guys spend all this money on the California condor but you don't have a condor exhibit at the zoo? How come?" Benedict asked.

"Zoos are changing. Zoos have gone from a place where you go to see animals to a place that does conservation locally and abroad," said Jake Owens, the director of conservation at the zoo.

Clark helped bring four birds who hatched last year to a wildlife refuge two hours north of Los Angeles, where they could fly off to their new home in the mountains. "You're just hoping that you prepare them to survive," he said about letting them go.

Since the recovery program began, the condor only has a 50% survival rate. It's still threatened by hunting, lead poisoning and hazards. Clark is training the birds to stay away from one of those hazards: power lines.

"We call it an e-perch, the electric perch," he said. "If a bird lands on it, they get a little shock and they avoid it."

But the juveniles usually learn this from an older wiser condor, a mentor, placed with them. "The mentor already knows about the pole and never uses it. None of them even try it, so that tells you how important the mentor is," Clark said.

As a new flock was tagged and prepped for release, the keepers were hopeful.

"Can you imagine walking out in your backyard and seeing a bird with a 9.5-foot wingspan sitting on your fence post?" Clark asked.