"Landmark" study shows breast cancer drug Xeloda can extend lives

A drug called Xeloda can extend the lives of some women whose breast cancer is not wiped out by standard treatment, a new clinical trial finds.

Oncologists said the results are "practice-changing."

"This drug is already approved, and we've been using it for a long time in cancer treatment," said Dr. Stephen Malamud, an oncologist at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Xeloda (capecitabine) is a pill, so it's easy to take and is "much less toxic" than standard chemotherapy, noted Malamud, who was not involved in the new research.

"Most importantly," he said, "it extended overall survival in this study."

In 1998, Xeloda was approved in the United States for advanced breast cancer that had spread to distant sites in the body. The new trial, done in Japan and South Korea, tested the drug for a different group of patients.

It focused on 910 women whose breast tumors were not completely eliminated by standard chemotherapy and surgery. In addition, they all had cancer that lacked a protein called HER2 -- which meant they could not benefit from breast cancer drugs that target HER2, such as Herceptin.

Those women have a fairly high risk of seeing their cancer progress, according to the researchers on the trial, led by Dr. Masakazu Toi, of Kyoto University in Japan.

In the study, Xeloda improved those odds. It cut patients' risk of relapse or death by 30 percent over five years.

At that point, 74 percent were still alive and recurrence-free, versus just under 68 percent of women who'd received placebo pills in addition to standard treatment.

"It's not a panacea, by any means," Malamud said. "But it's a nice 'back door' treatment to improve women's outcomes."

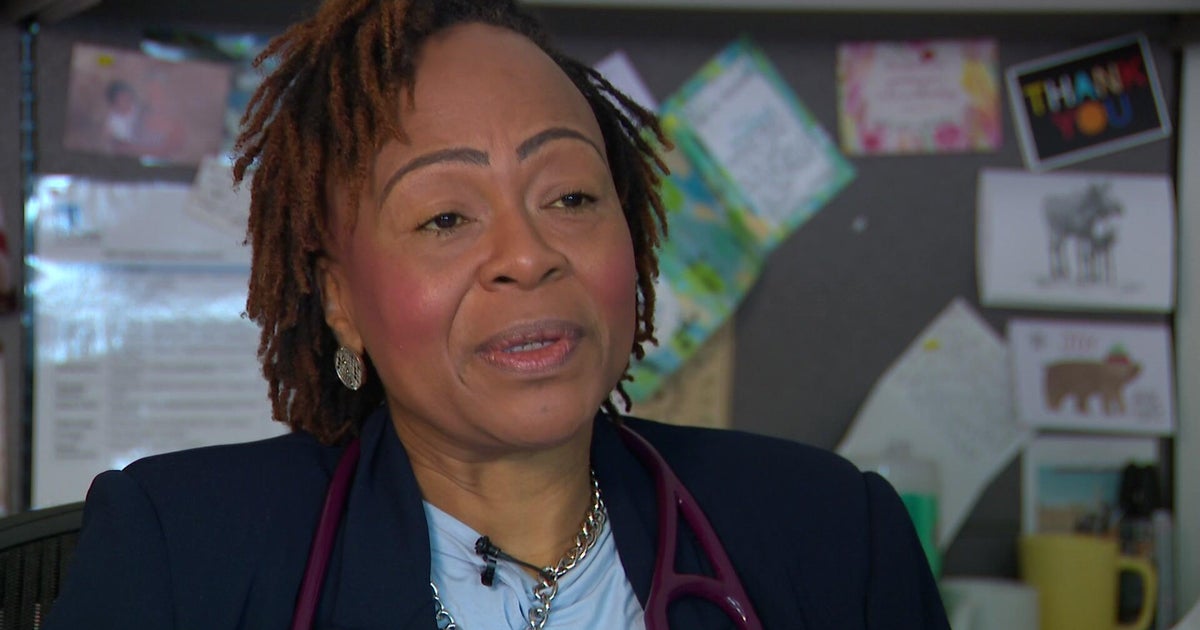

Dr. Elizabeth Comen is a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. She said doctors have already begun using Xeloda for women like those in the trial, based on preliminary reports. (The trial was actually stopped early, in 2015, when it became clear that Xeloda had benefits.)

"This is a landmark trial," Comen said. "It really is, in my opinion, practice-changing."

The women in the study all had breast tumors that had not yet spread to distant sites in the body. But many had cancer in nearby lymph nodes.

They'd all received standard chemotherapy before surgery, but still had "residual" cancer left behind.

Toi's team randomly assigned the patients to one of two groups. Most women in both groups received radiation, and those with hormone-sensitive breast cancer started on hormonal medications.

Only one group received Xeloda, while women in the other group were given placebo pills. The treatment was given in six or eight three-week "cycles," with two weeks on the drug, one week off.

Five years later, 89 percent of Xeloda patients were still alive, compared with just under 84 percent of placebo patients.

The difference was larger among women who had "triple-negative" breast cancer; that means their cancer not only lacked HER2, but was not hormone-sensitive, either -- which limits their treatment options.

Among those women, 79 percent of Xeloda patients were alive after five years, compared with 70 percent of placebo patients.

The main side effect -- affecting almost three-quarters of patients -- was hand-foot syndrome. That's a reddening and swelling of the palms and soles of the feet. It's similar, Malamud said, to a "bad sunburn," and it goes away once the drug is stopped.

According to Comen, the dosing of Xeloda for any one patient can be individualized to help manage side effects. The dose can be lowered, for instance, or a patient can take a short "holiday" from the drug, she said.

As for access to the drug, both Malamud and Comen said they would be surprised if an insurer wouldn't pay. Malamud said he has not encountered problems with coverage.

"This study is a demonstration that cancer cells not killed by certain drugs can still be killed by others," Comen said.

And, she added, it "drives home" the fact that researchers are continuing to make progress against hard-to-treat breast cancer.

The trial was funded by the Advanced Clinical Research Organization and Japan Breast Cancer Research Group.

The results were published June 1 in the New England Journal of Medicine.