Boys Town: A beacon for troubled youth

“There’s no place like home.” Rarely is that truer than this time of year. Our Christmas Cover Story is all about a very special home for some very needy children, as reported by Tony Dokoupil:

Right near the midpoint of America, ten miles outside of Omaha, Nebraska, there’s a town that sits between childhood and whatever comes after.

“These young people are about to become citizens of the most famous village in the world,” said Father Stephen Boes at a swearing-in ceremony.

In this town, almost every kid is at a crossroads -- and the goal of all the grown-ups here is to help kids leave Boys Town behind.

“I do solemnly promise … that I will be a good citizen.”

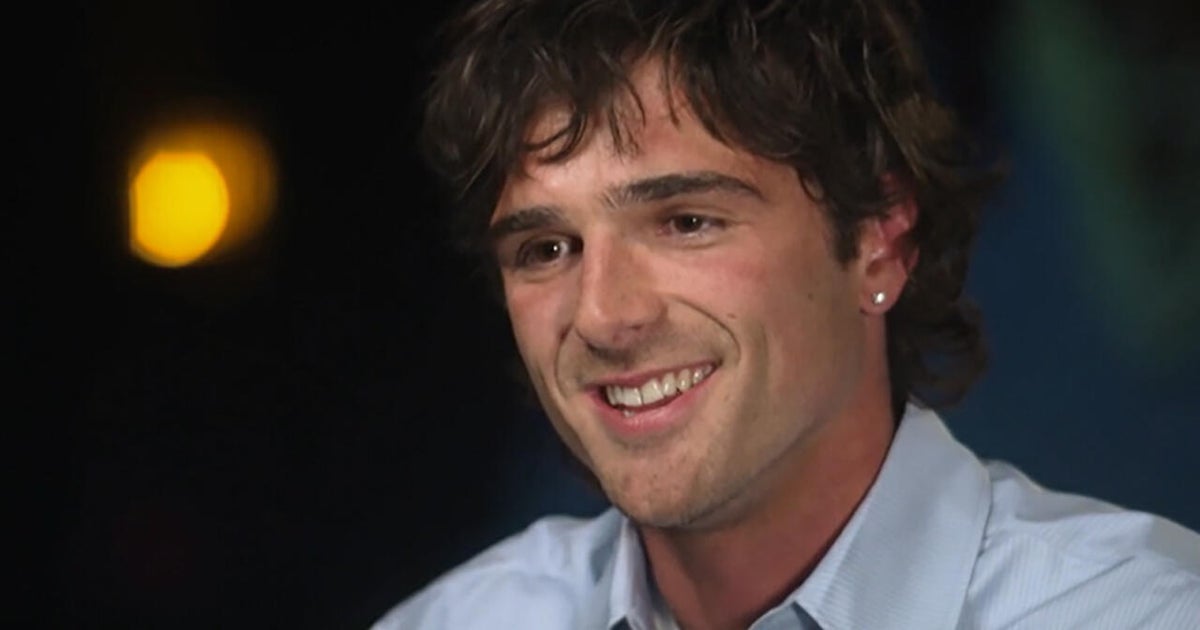

Eighteen-year-old Chase Pruss, from Dodge, Neb., was sworn in here six months ago -- arriving, like a lot of the kids, straight from jail.

“I took the school safe,” he said. “Just for money. For Beer money. And gas money. And buy cigarettes.”

Two more break-ins followed, and Pruss ended up arrested in front of his bewildered parents. “My mom was crying, my dad was crying,” he said.

He had run through four different schools, stolen and lied.

And he faced 80 years in prison, until a judge helped get him into Boys Town. “I had that mindset of, “I never want to ever put myself in the position where I could land myself back in an orange jumpsuit,” Pruss said. “I never wanted my jail ID number to say who I was.”

Seventeen-year-old Andre Harris came to Boys Town the same way. Nearly three years ago, back in Amarillo, Texas, he stole a car, and ended up in juvenile detention.

“I didn’t feel like I was gonna amount to anything after that,” he told Dokoupil.

Frankly, he didn’t think he’d amount to much before jail, either. College seemed out of reach. He can’t remember hearing someone say they were proud of him.

Dokoupil said of Boys Town, “More felons per capita here than any town in Nebraska.”

“Probably!” Harris laughed. “But we’re all doing our best to change.”

Almost every week here at Boys Town, new boys (and since 1979, new girls, too) are sent by social workers, judges and desperate parents. Most of the kids have been unable to live anywhere else without getting in trouble.

And Boys Town is their last chance.

“A lot of people would say they’re bad kids,” Dokoupil said. “Is that how they see themselves when they get here?”

“Some of our kids do,” replied Tony Jones, one of Boys Town’s “family teachers.” “They see themselves as, you know, on the bottom of the totem pole.”

And how do they change that mindset? “You show them that this is your decision. This is your life.”

Jones and his wife, Simone, run one of 55 homes on campus. Eight Boys Town children live there like a family, alongside the Jones’ three biological kids.

“Every single young man that has come through my home has now become a part of my family,” Jones said.

This is a large part of what makes Boys Town so powerful; all 360 kids living here have paid Boys Town parents like Tony and Simone.

“It’s a professional, full-time Dad, brother, uncle, cousin -- whatever my boys may need me to be at that particular time in their life, that, then, is who I become for them,” Jones said.

He began at Boys Town as a boy himself. He was born to a shattered family in Detroit. “I can recall my brother and I standing at a bus stop, and it was in the dead of winter. And we only had one pair of socks to share between the two us,” Jones laughed.

But then a priest gave the Jones brothers a chance to change their lives at Boys Town. “It was a total transformation,” he said.

Dokoupil asked, “Where do you think you would be if you had said no to Boys Town?”

“Oh, two places: I would either be incarcerated, or I would be dead.”

The Jones story is typical of a hundred years of stories at Boys Town, which began in 1917 as Father Flanagan’s Home for Boys. The most beloved clergyman in America, he created arguably the most famous reform school in the world.

Of his charges, Father Flanagan said, “His bruised and tortured heart and mind must be nursed back to normal health through kindness.”

You may remember a 1938-Oscar winning movie about the place starring Spencer Tracy. But what you probably don’t know is it’s a real town, with a real post office and police department.

At about $65,000 per student per year, Boys Town is comparable to a top private college -- and it’s mostly taxpayers footing the bill.

But taxpayers pay for prisons, too -- more than $39 billion a year nationally. Boys Town says it can help keep those prison cells empty, while nearly doubling the chance that these students will graduate from high school.

Dokoupil asked Jones, “How do you avoid coming in and being just another person telling them all the things they’re doing wrong?”

“By telling them all the things they’re doing right,” Jones replied. “That’s how you help kids change. It’s being able to say, ‘Hey, young man, you did a good job this morning getting up.’”

“It almost sounds like a joke.”

“Well, you know something? That little praise goes a long way.”

That little praise goes all the way back to Father Flanagan’s founding idea: “There are no bad boys.”

And if that all sounds too pat to be successful … well, the results say otherwise.

When asked where he would be without Boys Town, Chase Pruss replied, “I’d be in lockup.” As did another.

And if that all sounds too pat to be successful, just listen to the results. Tesharr said, “I’ve been here for a short amount of time. But since my first day I didn’t feel like I was in a place where I couldn’t leave. I felt like I was home.”

Of course, the Boys Town way does not work for every child who comes here; there are failures. But for Chase’s parents, Dan and Trish, it’s been nothing short of a Christmas miracle.

Dokoupil asked them, “Who was Chase before Boys Town and who is he today?”

“He was dishonest, disrespectful, a thief,” said his mother. “And now he is the Chase that I always wanted him to be.”

For Andre Harris, the change has been no less dramatic since stealing that car. “It’s not even the same person,” he said.

And how is he different? “My actions, the way I speak. I’ve grown up. I’ve become a young man.”

He’s a school leader now … a star on the track team … and he’s just found out he’s headed to college next year.

But first, he’s headed to Amarillo for the holidays … a place he hasn’t seen in nearly three years. It’s a place that Boys Town has been preparing him for since the very day he made his grand theft exit:

It’s home.

“This is my Christmas gift,” Robert Harris told Dokoupil. “This is all I wanted!”

For more info: